Today, it’s hard to imagine exploring or documenting your family history without sitting in front of a computer screen. So many resources are online: tree-building tools, other people’s research and historical records from all over the world. But what if your community lived almost entirely off the grid? And what if your family history lived only in the minds of older generations?

That’s the general experience of about 370 million members of indigenous communities in more than 70 countries around the world, says Golan Levi, an employee at genealogy website MyHeritage. Most of the time, Levi works to help MyHeritage.com users. But a few years ago, he began thinking about indigenous people who would likely never log in.

“For the most part, they live in isolated tribal formations, still maintaining ancient traditions,” says Levi. “But since they are now facing a constantly-growing overlap with modern society, their unique identity is gradually getting eroded or blurred. Some of those distinct groups are rapidly losing their cultures, traditions, languages and oral histories.”

Preserving the cultural heritage of indigenous societies

Though anthropologists and cultural historians are attempting to preserve the cultural heritage of many indigenous societies, Levi says it’s not enough. “As individuals, the vast majority of those people are nameless. Nobody knows their story,” he says. “Their family structure isn’t charted. Eventually, their memory will fade away, and their future descendants will know nothing about them.”

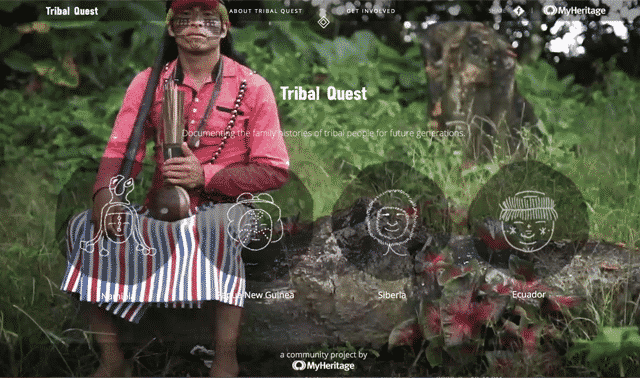

A few years ago, he proposed Tribal Quest, a pro-bono project to address this gap in recorded history. And the Tribal Quest teams’ journeys to record these communities’ memories—from vodka-laced rituals to curse-related adoptions—are stories all their own.

Tribal Quest Expeditions

Deciding where to take an expedition is the first big step for each Tribal Quest trip. MyHeritage prioritizes “remote destinations where our presence can make the most difference,” says Levi. But identifying potential groups, making contact and confirming arrangements isn’t easy with people who aren’t online and don’t speak your language.

That’s why a local intermediary makes initial contact with the groups, says Rafi Mendelsohn, MyHeritage’s director of public relations. After identifying a region of interest, MyHeritage works with local guides to better understand the people who live there: the culture, the genealogical challenges and what social or logistical difficulties the Tribal Quest team might face.

Namibia

So far, Tribal Quest teams have visited communities on four continents. The first expedition, in 2015, took them to northern Namibia. They met with the Himba people, whose semi-nomadic villages follow herds of cattle. Village elders offer prayers to ancestors, and strict rules of inheritance define the distribution of wealth from both parents.

Papua New Guinea

The following year, another expedition headed to Papua New Guinea, a nation of islands north of Australia, to meet five different tribes in three regions. “Papua New Guinea is one of the most culturally diverse places on the planet, with more than 800 tribes,” says Levi. Each speaks its own language: More than 10 percent of the world’s living languages can be found in this island nation. These groups practice their own form of ancestor worship and follow distinct rules defining marriage and family structure.

Siberia

The third trip took Tribal Quest to the tundra of Siberia. “We traveled to the Yamal Peninsula to meet the nomadic reindeer herders of the Nenets tribe,” says Golan. He says yamal literally means “edge of the world,” and that the Nenets “live under the most extreme conditions imaginable, with temperatures that drop well below -50°C at nighttime during the winter.” Here, family inheritances are both practical and personal: clothing or housing crafted by parents or reindeer-herding skills learned from fathers.

Ecuador

The fourth Tribal Quest focuses on the Achuar people of Ecuador. According to the website, “Their respect for the rainforest and deep understanding of its ecosystem are woven into the fabric of their day-to-day activities as well as their rich spiritual life. Under the guidance of local shamans, the Achuar communicate with Arutam, the spirit of the forest, through dreams, visions, and rituals.”

Team Selection and Trip Preparation

Tribal Quest trips are staffed by MyHeritage employees, and any may apply to go. But teams are chosen carefully. This isn’t an experience for the timid or those who require creature comforts. MyHeritage Senior Product Manager Shahar Bitton knows this firsthand; he’s been on all three trips.

“People need to be prepared to be far from communication,” he says. “They could be three to four weeks without talking with their friends and families.” Demanding travel and living conditions, unfamiliar cultural environments and living elbow to elbow with work colleagues and strangers are also part of the experience.

Tribe Research and Planning

Once a group is selected, its members begin to learn about the tribe and the region, meeting with a guide and learning the basics of life there. This includes learning what can and can’t be said, as well as any cultural taboos.

This preparation helps the team prepare to immerse themselves in the cultures they visit. “Each person is required to live as a part of the tribe,” explains Bitton. “We eat with them and sleep alongside them to break the ice and make them feel more comfortable with us. We really see the effects of this, too: the first few days they are more shy and closed, but as soon as the days pass, we see them become more comfortable and share more details.”

Just traveling to the destination requires thorough planning. After flying to the nearest airports, they may use a variety of local transportation options to reach the often-remote tribal homes. In Namibia, this meant four-wheel-drive vehicles equipped for desert terrain. A visit to Papua New Guinea meant motorized canoes transported them between villages. While in Siberia, in addition to snowmobiles and reindeer-drawn wooden sleds, they used a specially equipped six-wheel-drive Trekol vehicle to negotiate the arctic tundra and serve as a sheltered workspace.

Meeting the Tribes

The team’s first priority upon arriving is meeting the community they’ll be interviewing.

“We try to find the way to break the ice as soon as possible,” says Bitton. “These families are not used to sitting in a group in front of a camera where people interview them. It’s outside their comfort zone. We never just come with a camera and start interviewing.”

Playing games with children and helping with chores are two tried-and-true Tribal Quest icebreakers. So is dining together. “In Siberia, we had to sit down in a tent, eat and drink vodka,” says Bitton. “They wanted us to feel at home. So in Siberia, genealogy involves a lot of drinking. After a few shots of vodka, the names get a little fuzzy. But we try to stay professional.”

Respecting cultural boundaries sometimes requires even greater measures—especially for the women who comprise half of the Tribal Quest expedition teams. “In Namibia, there are rules about what women can and can’t do; it’s a very patriarchal society,” Bitton explains. “The male moves his chair according to where the shade is, and women do everything else. Women can’t step over a man lying on the ground, or take her things around or over him, or cross a certain line. I think they appreciated that we tried to follow their gender taboos even if they understood that’s not how we live.”

Gathering the Genealogy

After establishing rapport, teams start gathering family history information. “Our interviews include two parts,” Bitton explains. “First is an interview with an elder. We ask about the life of this person: memorable things from his childhood, and special events. The second part is building the tree, which is more technical, going person by person.”

These interviews take place wherever teams can find a comfortable spot for a long conversation. This might be under the shade of a tree (until the sun moves) or sitting on the floor of a dark hut (until it gets crowded with onlookers). Expedition photos show a team sitting under a hut in the pouring rain, the raised poles providing enough dry shelter for relatives to sit nearby and listen.

The Importance of Storytelling

And they do often listen, says Bitton. An interview might start one on one, but crowds grow whenever someone tells stories. Sometimes listeners are quiet for a while. But eventually they have something to add, and what started as a private narrative becomes a lively group conversation.

The stories they share can be intimate. “A lot of the time you get to hear very personal parts of someone’s family history,” Bitton says. He describes one in Papua New Guinea, when an elder began explaining the tribe’s spiritual origins. Younger listeners started asking questions, and suddenly the Tribal Quest members weren’t the interviewers any longer. The elder started to cry.

“He said that all his life he’s trying to tell the story to the younger generation, and they don’t care—they’re busy. It was the first time for him to be able to pass on the story to the younger generation,” says Bitton. “All of us cried at that moment. For us, it was a privilege to provide this scene where they could do it.”

DNA Testing

DNA testing is available to Tribal Quest participants, but it’s not a planned part of the experience. According to Bitton, DNA was discussed on the Siberia trip, but not the others. The translator provided information, explaining DNA was another way of documenting heritage. Any DNA tests taken during Tribal Quest are not incorporated into MyHeritage’s Founder Populations project, which forms the reference population for MyHeritage DNA’s ethnicity analysis.

Challenges and Surprises

It’s not easy to construct someone’s family tree or record stories about their lives in another language, so Tribal Quest teams take translators to help them. But other challenges have arisen. Some tribal communities don’t have documentation or memories for specific dates of vital events. Cultural practices, such as polygamy (practiced by the Himba culture), may also complicate tree-building.

A couple of cultural practices took Tribal Quest staffers entirely by surprise. “In Namibia, as part of their culture, they’re not allowed to say the names of their deceased ancestors, out of respect and fear of the spirits,” Bitton says. “How do you build a family tree when they can’t say their father’s name?”

Fortunately, others who were listening soon recognized and solved the problem. Someone else in the group would call out the name of that person’s father, then everyone would laugh.

A second surprise came up in Papua New Guinea. According to Bitton, adoption was prevalent in the community for unexpected reasons. Two siblings might exchange children so that each had a son, or parents of three children who died young might give up their fourth child because they were believed to have a bad spirit haunting them.

Documenting and Organizing Family History

One of the biggest tasks of Tribal Quest team members is to document and organize the family history data they gather. They do this in Family Tree Builder, MyHeritage’s free genealogy software. Bitton’s day job makes him an expert on Family Tree Builder, and it’s one of the reasons he was chosen for Tribal Quest expeditions.

The software proved flexible enough to accommodate all the different family relationships the team encountered. The key to recording the nuances of a complicated or unusual family relationship, he says, is liberal use of the notes and stories tools.

Each tribe’s trees, stories and photos are eventually uploaded to private MyHeritage accounts for each indigenous community so that the digital version is available to future generations. The team gives account access details to the most technologically savvy members of the clan, or to those who have the best Internet access.

Because so many members of indigenous tribes live entirely or almost entirely offline, MyHeritage staffers also print and send tree charts, similar to those available on their website.

So far, Tribal Quest excursions have documented more than 10,000 people in trees, oral histories, photos, video interviews, artifact descriptions and personal and family stories. The single biggest tree created for Tribal Quest so far is for about 750 people in Papua New Guinea, and it records seven or eight generations.

“We got all their elders together, and got more and more details,” says Bitton. “In their culture, they started from a spirit who came down and had a child, and it got to the point where we didn’t know whether it was myth or reality, but that’s their story—that’s their family tree.”

Benefits to the Global Community

From the outside looking in, you might wonder how the Tribal Quest initiative benefits the global community, or even just MyHeritage users. Is the long-term goal that outside communities will connect their trees to Tribal Quest trees?

That’s possible, says Mendelsohn, but not the project’s chief goal. “The main benefit is that we can collect and store the tradition and the memories and family trees for all of these tribespeople before they disappear or are lost. These tribes themselves are the main beneficiaries and the intended target of these projects.”

In each place, team members encouraged tribal communities to document their own family histories moving forward. One man in Papua New Guinea, Jack, was already doing so with notebooks of names and births and deaths. Bitton and the team shared some suggestions for how to better organize the document, and (a few months after the visit) Jack contacted Bitton with an updated list of new babies born.

Participation and Motivation

Bitton was surprised—and deeply moved—to discover that one of the babies had his own name. Members of the tribe have both a local, native name and a Christian name. One child’s Christian name was Shahar, after Bitton. “For me that was absolutely amazing,” says Bitton. “I emailed [Jack] and asked if that was true, and he said yes, they decided to name the baby after me. It just shows how important our visit was for them.”

Participating villages in one country had another huge motivator for documenting their family trees. According to Bitton, heritage governs land ownership in Papua New Guinea. “Usually they have to pay the government to build their family trees for them, but suddenly we came out of nowhere, and we offered to do it,” he says. “We weren’t aware of that. It’s something we learned when we got there.”

Photos were another popular benefit. “Everywhere they went, the teams took a Polaroid camera and took pictures of the family,” Bitton says. “Some of them had never seen that technology before.” Anticipation would grow as the picture slowly printed, and for some, these represented the only images they had of themselves or their loved ones.

A Lasting Impression

The MyHeritage employees who participate in Tribal Quest bring home a new perspective on what they do. “Genealogy is part of my daily work, but Tribal Quest gives me an opportunity to get exposed to the actual work of documenting family history on a whole new level,” says Bitton. “It’s not just the names and dates: it’s stories, artifacts and the faces behind those names and dates.”

He also internalized a vital lesson he thinks everyone can learn. “Tribal Quest shows us that we are more similar than different. We care about the same questions: what will my children learn from me, what will they take with them, what will they remember, how do we cherish our heritage?”

“On a high level for the global community, that’s the most valuable thing you can take from Tribal Quest,” Bitton says. “It’s an amazing example of how it’s all about the family, all around the world.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 issue of Family Tree Magazine.