Do you know how to eat an elephant?” asked a friend. “Not a clue,” I replied. “It’s easy,” he said. “Just do it one bite at a time.”

The Internet is a lot like that elephant — especially when it comes to climbing your family tree. With millions upon millions of Web sites, in no particular order, how in the world can you find a single ancestor?

You do it one bite at a time. May we offer you a fork?

Genealogist, meet the Internet

The Internet started in 1969 as a network named ARPANET It was funded mainly by US military sources and consisted of several individual computers connected by leased lines. In the 1980s, ARPANET was replaced by a new, separate military network and a net-work of scientific and academic computers funded by the National Science Foundation.

The Internet as we know it is a relatively new member of the family, with its commercial roots extending back only to about 1992. Today’s Internet is a massive grouping of millions of computers, all linked together on a network. All of the computers can communicate with one another through the network. Briefly, here’s how it works.

Your home computer communicates with the computer owned by your Internet Service Provider (ISP). Your ISP then talks to other ISPs around the world via fiber-optic lines, undersea cables or satellite links. When you want to view a specific Web page, your server sends a request, which makes a series of hops between the user’s server and the server hosting the page on the Internet, asking that the Web page be sent to you.

Each Web page has a unique “address.” If you want to get to a specific Web page, you need to tell the browser its address. In Internet lingo, that address is known as a Uniform Resource Locator (URL). A URL looks like this: www.familytreemagazine.com/store.

Without boring you with the technical details, a URL tells the network which Web page you want to view on your browser. In this instance, you’re telling the network that you want to go to the Web site of Family Tree Magazine and view the page that contains the bookstore (store).

As you can tell, URLs are organized a lot like the directories on your own computer. For example, if you use a PC, your computer contains a main directory called Windows, and several subdirectories, among them Icons, System, and Start Menu. In the example above, “familytreemagazine.com” is the main directory, and “store” is a subdirectory.

Why do you need to know this? Web-site addresses do change, and if you understand the basic structure of a URL, you can often find a page even when its address has changed. Hypothetically speaking, if you click on a link such as www.someaddress.com/pedigrees/jerryjones.htm and you receive a message saying the page cannot be found, you just delete the jerryjones.htm part of the address. Then, hit Enter on your computer and see what comes up. You’ll often be able to find the page from a new or corrected link.

Gateway to the Web

Today, Cyndi’s List welcomes 15,000 visitors daily and hosts close to 200,000 genealogy links, with 1,500 links added monthly. Sites are organized alphabetically within one of 120 categories. Although you won’t find actual family data on Cyndi’s List, you will find links to any number of topics that will assist your research.

The best way to use Cyndi’s List is if you have a general topic of interest. For example, if you know you have a Quaker ancestor, but don’t know anything about searching Quaker records (or even where to find them), go to Cyndi’s List and click on Quaker, where you’ll find the Quaker category further organized into 11 topics such as general resource sites, history, mailing lists and records. In all, there are 140 Quaker links to explore, depending on the type of information you’re seeking. If you’re starting from square one, visit the general resource sites; if you’ve already used William Wade Hinshaw’s Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, follow the How To link for more information on Hinshaw’s system of abbreviations. Are you keen on networking with other Quaker researchers? Then follow the Mailing List links.

Another excellent way to use Cyndi’s List is to track down state-specific resource sites. If your family settled in South Carolina, for instance, go to the Topical Category Index, then Localities, then United States and finally, the South Carolina category to explore more than 1,300 South Carolina-related links. There, you’ll find links to sites with maps, military rosters, records and information about religion and culture. If you need to hire a professional genealogist who’s skilled in a specific area, you’ll find links to researchers in the state categories.

For anyone who has discovered overseas ancestors, Cyndi’s List is a good jumping-off point. For example, if you’ve just discovered you have Swedish ancestors, click on the Sweden link, and you’ll find dozens of useful reference sites, such as a Swedish Research Outline or tips on the language, churches and Swedish naming customs.

Whenever you start a new area of research, be sure to visit Cyndi’s List for links to vital background information.

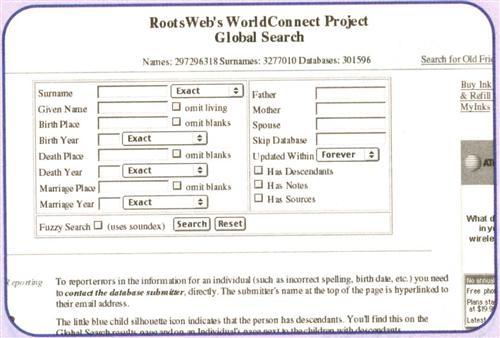

If you think of the Internet as a genealogist’s version of Wal-Mart, you’ll have a good idea of what information is online. In other words, there’s a little bit of everything. When you visit one of the major genealogy information Web sites, you will likely need to search its database for facts about your family. A database is a large collection of information organized for quick searches and retrieval. Genealogy databases typically contain transcribed records or compiled family histories. For example, a marriage database might include the name of the bride and groom, the date, and the town and county where the ceremony was performed.

What you often won’t find are the extras that appear on an actual record. These may include the names of the witnesses, minister or justice of the peace, and peripheral notes such as “performed at the home of the bride’s brother, Jonathan Sutton.”

Database-friendly documents contain basic name-date-place data — think cemetery records (date and place, but not art carvings), immigration records, land records, marriage certificates and military rosters.

Records that aren’t database-friendly contain text that doesn’t easily fit into a name, date or place field. These include documents such as medical records (type and length of illness, attending physician), military enlistment papers (soldier’s physical description, notes by the recruiting officer), pension files (description of military service, including specific battles and the ancestor’s health), probate files (itemized property list, debts) and wills (detailed account of the individual’s last wishes).

This doesn’t mean you won’t find a pension file online — it’s possible that someone transcribed and uploaded it to a Web page. In fact, volunteers work daily to transcribe tombstone inscriptions, probate files, wills and even Bible records. But this type of record is more likely to be sitting on a volunteer’s personal Web page than on a large, database-driven site. One exception is USGenWeb <www.usgenweb.org>.

All sorts of sites

Genealogically helpful Web sites tend to fall into four categories:

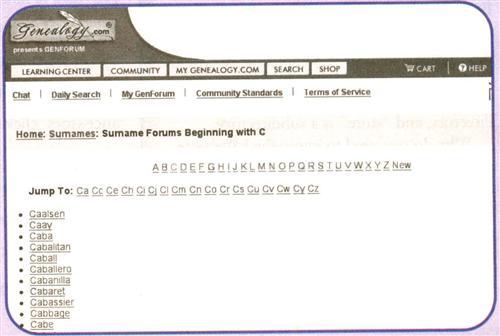

As much as everyone loves free genealogy, the day will probably come when you subscribe to a commercial database site. These sites contain thousands of genealogy-specific databases or other hard-to-come-by family files. Currently, the two largest services are Ancestry.com <Ancestry.com > (see page 30) and Genealogy.com <www.genealogy.com> (see page 46), both owned by MyFamily.com. Each Web site offers an assortment of subscription plans, including monthly, quarterly and annual billing options.

3. Search engines: You’ve probably run into family history-related search engines that scour genealogy-only Web sites for your surname. You can be even more successful — particularly when you’re looking for a specific piece of information — by using general search engines such as Google <www.google.com> or Alta Vista <www.altavista.com>. Most good search engines — by good, I mean the ones that return hits most relevant to your search — allow users to structure complex searches. That means you can create a search with a high probability of pinpointing exactly what you’re looking for.

4. Other databases: These Web sites are the searchable collections of a variety of data. They may contain GEDCOMs (see sidebar on page 10), births, burials, city directories, pioneer names or ships’ passenger lists. Some of these databases are free; others, such as the ones at Ancestry.com and Genealogy.com require a paid subscription.

Online transcriptions are genealogically relevant pieces of information that have been copied (usually by volunteers) and uploaded to the Internet. The most commonly transcribed records are federal census returns. You might find transcriptions of wills, probate files and headstone inscriptions, as well.

Don’t forget about the wealth of information available from “peripheral resources,” even though many aren’t even genealogy Web sites. These might tell you which president your great-grandpa may have voted for, how Great-great-granny probably dressed or what games were popular a century ago. Site topics include history, photographs, maps, books and state resources.

Most of your searches will entail using all of these sites: free lineage-linked databases, networking tools, search engines and online databases and transcriptions. For example, if you search a database site and find a reference to your great-grandmother’s marriage, what would you do next? You’d obtain a copy of the record, but you also might try to find other people searching for her family. And you’d probably look for information about where she lived, where she might have come from, where her parents were married and where she’s buried.

Be prepared

Before going online, gather your tools just as you would for a library trip. Have your pedigree chart and any family group sheets that include your target individual. If you want to keep all your notes in electronic format, fire up your favorite word processing program or your genealogy software program. Next, open a new file and name it whatever surname you’re looking for (or open the appropriate file in your genealogy software). Then, as you search, make notes in that file of the date you searched, the Web site or sites you searched and your results. If you don’t find anything with this particular search, note that, too.

If you get in the habit of keeping research notes as you move from Web site to Web site, you’ll become a more efficient researcher. It’s hard to remember all the sites you’ve visited and the details you found there, so keeping consistent (and current) notes will make it easier to plan future online research. When I first started doing genealogy research, I was terrible at keeping accurate records. In fact, I’m too embarrassed to confess how many times I’ve searched the same census micro-film, just because I didn’t write down all the information I should have the first time I found it. Going back over the same census records — or visiting the same Internet site — multiple times because you didn’t take thorough notes is a waste of time. That time could be better spent searching new sources. (Of course, you’ll want to return to certain Web sites to see if new records have been posted.) Here are the types of online sources to record and file:

? Web site URLs where you found data

? Web sites where you posted queries

? Web sites that didn’t have what you wanted, but which you want to check again, in case new information is added

? Web sites with free databases

? Web sites where you didn’t find anything useful (to avoid revisiting sites that yielded negative results)

Search and re-search

As Grandma used to say, “There’s more than one way to skin a cat.” Same with searches. Keep in mind that the pedigree files on data-base sites were submitted by thousands of individuals. It’s possible (and likely) that the same ancestors will show up in several search results, with slightly different information. For example, one search may list a daughter as Jenny and another may show her as Jiny. This means you may need to conduct this search more than once, using different approaches each time. How can you do this? Try entering the individual’s name and the father’s name, but not the mother’s; or enter the mother’s, but not the father’s. Try a spouse’s surname and a father’s surname, or use a surname and country only. Remember, being a genealogist is like being a detective. If one line of questioning doesn’t work, switch to another.

Even if you find information with your initial search criteria, search again using different criteria. Here’s why: If you know an ancestor had the surname Ludwell and was married in Indiana, you may use Ludwell and Indiana as your search criteria — and you may find that marriage record. What you may not find is Ludwell’s birth in Tennessee. Play around with adding and subtracting search filters to increase your chances of finding additional details.

Doing downloads

Certainly, one of these days you’ll want to download a file or program from the Web to your computer. Your first thought is probably “No, I won’t, because I don’t want to get a virus.” Don’t worry. If your anti-virus software is updated and properly configured, it will automatically scan any downloaded files (see box at right).

What would you download? When I searched the FamilySearch Web site <www.familysearch.org> for more information on Frances Easley, I found GEDCOM files that traced her family to 1588. Of course, I immediately downloaded the GEDCOMs for further research and examination.

To download a file, just click on the file name (or a Download link). Your browser will pop up a box asking you if you want to open the file, save it, or cancel the operation. (Browsers vary a bit in how they handle this, but the process is basically the same). Click Save. Another box will pop up, asking you in which directory to save the file. Use the pull-down menu to select your GEDCOM directory (or another location where you keep genealogy files), then click Save.

You also can right-click the file name, and in Internet Explorer pick the menu choice Save Target As, then choose the directory where you want to download the file. Using Netscape Navigator, right-click and choose the menu item Save As. On a Mac, hold down the mouse button and select the Down-load option.

Proceed with caution

Just because you find information online doesn’t mean it’s accurate. Think of your online finds as clues leading to original records. When you luck into finding family in one click, it’s tempting to jump back generation after generation, downloading GEDCOMs like mad. Remember to verify the connections in original documents so you don’t end up tracing the wrong ancestors.

If you’re new to Internet genealogy, you’re in for the ride of your life. You’ll have the opportunity to uncover generations of family and meet cousins you never knew existed. You’ll be thrilled with the connections you “make and the family you find. Mmm … that elephant is tasting better every minute!”

Virus Hoaxes

What is GEDCOM?