Searching genealogy websites is like shopping for a suit or a dress: One size doesn’t always fit all, sometimes even for clothes from the same label. Search functions on major genealogy websites all work differently, too. What’s more, search tricks can vary from collection to collection within one site, particularly when it comes to census and book collections.

But there’s no need to hem and haw about the differences. We’ve explored top genealogy sites to give you the inside line on the key differences (and similarities) among the sites and their search capabilities. Our tips on altering your search terms and taking advantage of wildcards will help you customize your searches for each site. Let’s get started needling in on census records and books to find your ancestors.

Altering names

Whether you’re searching census records, books or other sources, there’s a good chance you’ll encounter problems with names. Misspellings or nicknames in original records, inaccurate transcriptions and name changes all can prevent you from finding your ancestors’ records. Online databases use three key search tools—authority-based searching, Soundex and wildcards—to help you get around these problems.

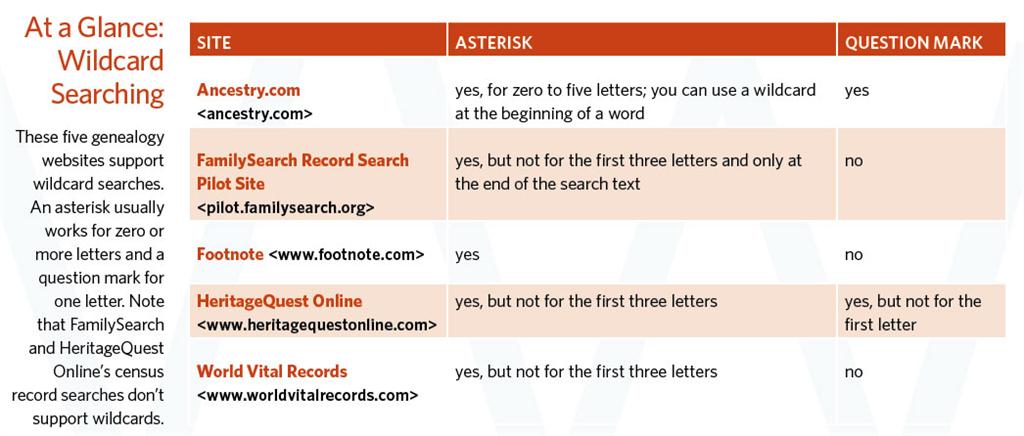

Authority-based searching: Unless you specify an exact spelling, FamilySearch and Ancestry.com automatically find alternate spellings (such as Olsen and Olson), foreign equivalents (John and Johann), nicknames (Becca or Becky) and abbreviations (Wm. for William). Still, these sites don’t catch every likely match. Looking on FamilySearch for Elizabeth Olmsted returns Betsey Olmstead, but not Lizzie Olmsted. Matches for Shaubhut don’t include Schaubhut and Shaubut, two alternate spellings in my family. If you search Ancestry.com for William Smith, records of Wm. Smith might appear far below much less likely matches. So even with the advanced technology on FamilySearch and Ancestry.com, it’s worth searching for alternate forms of a name.Soundex: Census takers often spelled names the way they sounded. First widely used to index US census records, Soundex helps genealogists find spelling variations of surnames. Most databases on Ancestry.com’s “Old Search” let you do a Soundex search. If you check the box for “Exact matches only,” you get two spelling options: Exact or Soundex. Search the 1800 census for the exact spelling of Tobias Schaubhut, and Ancestry.com delivers no matches, but if you use Soundex the results show his name recorded as Tobias Shafwood.The Advanced Search in Ancestry.com’s Old Search interface offers no Soundex option because Soundex matches are automatically returned if you don’t check Exact.In the New Search, just-added filters let you specify options including a Soundex search for the surname. The default filter finds exact, Soundex and similarly spelled matches.In addition to Exact and Soundex searching, World Vital Records’ Advanced Search gives you another surname matching option called Double Metaphone, which is similar to Soundex but more accurate. Soundex and Double Metaphone can produce a lot of clearly false matches, so it’s usually helpful to add other search criteria, such as a location or an unusual first name.Wildcards: Many websites support wildcard searching, in which you use a special character to substitute for variable letters in a name. This lets you do a single search for alternate name spellings, rather than many searches on alternate spellings, and it catches spellings you might never have dreamed of. Most sites let you use either an asterisk (*) or a question mark (?) as a wildcard. Usually an asterisk stands for zero or more letters, and a question mark stands for a single letter.For example, although my immigrant ancestors from Scotland spelled their name as Robertson, it’s rarely spelled that way in US census records. If you search Ancestry.com’s census collection for John Rob*son in New York, it catches the spelling Robinson in 1810, 1820, 1830 and 1850, Robbinson in 1840 and Robison in 1860. Footnote supports the asterisk wildcard, too, but HeritageQuest Online’s census collection doesn’t.Additionally, John Robertson’s wife Elizabeth is recorded as Elisabeth Robinson in the 1850 census, Elisebuth Robison in 1860 and Betsey Robertson in 1870. A search on Elizabeth Rob*son on Ancestry.com produces a match in 1850, but not in the other two years. So if your first search fails, search for other family members, try nicknames and use additional criteria. If you know where the family lived, search on just a first or last name combined with the town and county.While many sites require you to input a minimum number of letters before the wildcard, Ancestry.com lets you put a wildcard first, so you can search on *muel to find Samuel or Lemuel. That’s especially helpful with capital cursive letters that look similar, such as L and S. The first or last letter must be a non-wildcard character, and names must contain at least three non-wildcard characters. Keep in mind that wildcards aren’t limited to personal names on most of these sites. A place name search on Pittsburg* returns Pittsburg and Pittsburgh.HeritageQuest Online’s book collection automatically finds words that begin with your search terms. Search on mission or mission*, and matches include mission, missions, missionary and missionaries. Both Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online’s book search let you use a question mark as a wildcard for a single character. A search for Ols?n finds Olson and Olsen, but not Olsson or Olssen.

Sewing up censuses

The federal census ranks among the top resource for American genealogists. Enumerations took place every 10 years beginning in 1790. They list only heads of households until 1850, when enumerators began listing all residents, with the notable exception of slaves. Federal census records are released to the public after 72 years, so the 1930 census is the most recent year available to the public. Most census records from 1790 to 1930 still exist, but almost all of the 1890 census was lost.

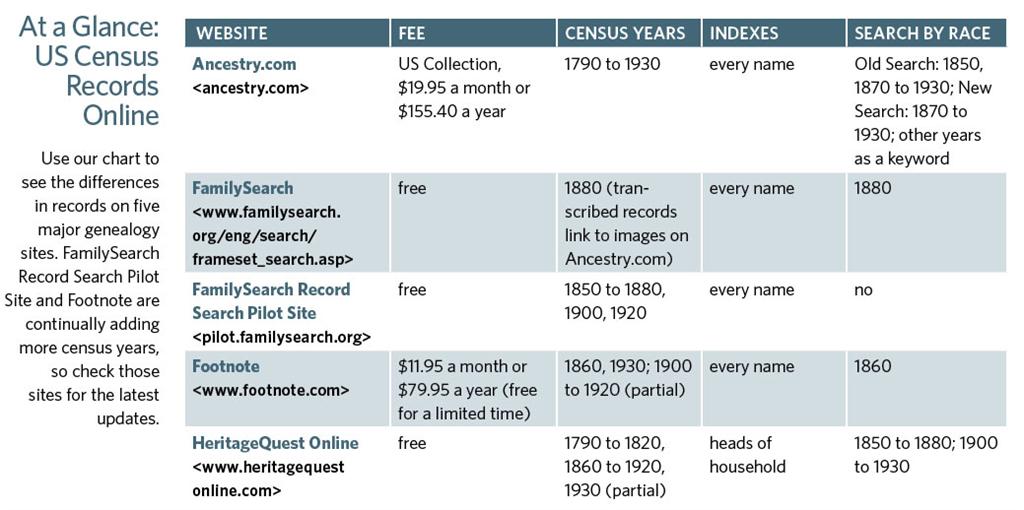

For the most comprehensive census records, you need a subscription to Ancestry.com or access to a library that subscribes to Ancestry Library Edition. Ancestry.com is the only site that provides online access to all the census records from 1790 to 1930 with every-name indexes and census images. User-contributed corrections also greatly enhance Ancestry.com’s census indexes.

Footnote also has several census years online and plans to complete its collection by the end of 2010. In addition to the FamilySearch 1880 US census lookup, the FamilySearch Record Search Pilot Site has indexes or images for several US censuses (it eventually will have indexes and images of all US census records from 1790 to 1930). HeritageQuest Online’s indexes (available at subscribing libraries) include only heads of household and residents whose surnames are different from the head of households’.

Of these five sites, only FamilySearch requires you to enter the last name of the person you’re searching for. Omitting the surname is helpful if you don’t know a woman’s married name. The 1900 census of Spokane, Wash., shows Meda H. Nickerson born in 1879 in Maine, living with her widowed mother and brothers. If you search the 1930 census on Ancestry.com or Footnote for just Meda H. born in about 1879, without specifying a surname, you’ll find Meda H. Arant, married with children, in Glendale, Calif.

As the census comparison chart below shows, several sites let you search the census by “race.” The available choices for race changed from census to census and included Chinese in 1870, 1880, and 1900 to 1930; Italian in 1900 and 1910; Russian in 1900; and Greek in 1910. When searching by race, keep in mind that it wasn’t recorded consistently. For example, the race of an American of Italian descent might be recorded as Italian or White.

Beginning with the 1850 census, HeritageQuest Online lets you search by race, but gives only these choices: Black, Chinese, Indian, Japanese, Mulatto, Other, White and Not Recorded. If you search the 1880 census on HeritageQuest Online for a John Johnson born in Massachusetts, you get 135 matches. Selecting Black as the race reduces that to four.

Ancestry.com lets you search on any of the terms used for race in the original census records. The Old Search forms for 1850 and 1870 to 1930 have a Race field that lets you select from the available options for each census year, such as Black, Colored, Copper, Indian, Mulatto, White and Yellow for the 1850 census. Ancestry.com’s New Search just gives you a blank box when searching by race for the censuses from 1870 to 1930, so you need to know what racial and ethnic terms were used in each census year. There’s no field for race in Ancestry’s Old Search forms for 1790 to 1840 and 1860 or the New Search forms for 1790 to 1860, but you can enter a race or ethnicity in the Keyword(s) box. Use Negro, Colored, Mulatto, Free Black, F B (for Free Black) or F N (for Free Negro) to find free blacks and Indian to find American Indians.

Pre-1850 federal censuses give only the names of heads of household and statistics on the number of whites, slaves and free colored people in each household. Ancestry.com is transcribing those numbers, so you can do more precise searches of these census years.

Each website has a few quirks. Heed these strategies to produce the best census search results:

Ancestry.com: The index covers more than just the names from the census records, giving you multiple ways to focus your search. For example, on the search forms for the 1880, 1890, 1910 and 1920 censuses you can search on parents’ birthplaces (you must use the Old Search option, accessible on your results page). Doing an exact-matches-only search of the 1920 census for John Smith, born between 1865 and 1867 in New York, returns 96 matches. If you narrow the search to only John Smiths whose fathers were born in Ireland and mothers were born in New York, it returns three matches.FamilySearch: This site ignores middle names or initials you enter unless you check the box “Use exact spelling.”FamilySearch Record Search Pilot Site: To search a specific census year, click Browse our Record Collections and then Canada, USA and Mexico. Scroll down and select the census database you want to search.You can search on either year and place of birth, or place of residence at the time of the census. To find my ancestor Thomas Morgan in the 1850 census, you could enter his first and last names, select Birth/Christening as the Event and enter 1788 as the year. Enter Wales in the Location field and select the standardized name, “Wales, United Kingdom,” from the list.To search by his place of residence in 1850, enter his first and last names, leave “All events” in the Event field unchanged. Enter Pennsylvania in the Location field and select the standardized name “Pennsylvania, United States.” (If you knew the specific town or county, you also could search on “Athens, Bradford, Pennsylvania, United States.”) Then click the Search button.All databases on the FamilySearch Record Search Pilot Site use the same generic search form. When searching census records, the Marriage and Death/Burial events and parents’ names don’t apply, so don’t use them.Footnote: On this site, you might want to start your search with just a surname and then focus your search from there. For example, type Cooley in the search box and hit the Search button. Under Title or Collection, select Census—US Federal 1860. That narrows the matches to 5,519. Scroll down, click on State, type in New Hampshire and click on New Hampshire. That narrows the matches to 59, and my ancestor Ithamar Cooley (transcribed as Ithaman Cooley) shows up on the second page of results. You also can refine your search by other criteria such as age and birthplace.HeritageQuest Online: Even though US federal census records often list a place of birth as a specific Canadian province, HeritageQuest Online indexes all of them as just Canada, and there are likely other examples of place names standardized for indexing purposes. So rather than typing a place in the birthplace box, browse the available options.

As you search these sites, remember that transcriptions can vary from site to site. So if you don’t find a name in the census records on one site, try another one.

Buttoning up books

You can access tens of thousands of family and local histories online. Millions of other books that might mention your ancestors, such as biographies, also have been digitized. Most online book collections include scanned images of book pages. Creating a comprehensive index of all the names in these books would be very labor intensive, but optical character recognition (OCR) automatically creates a searchable text file of each book so you can search for a word or phrase in one book or a million.

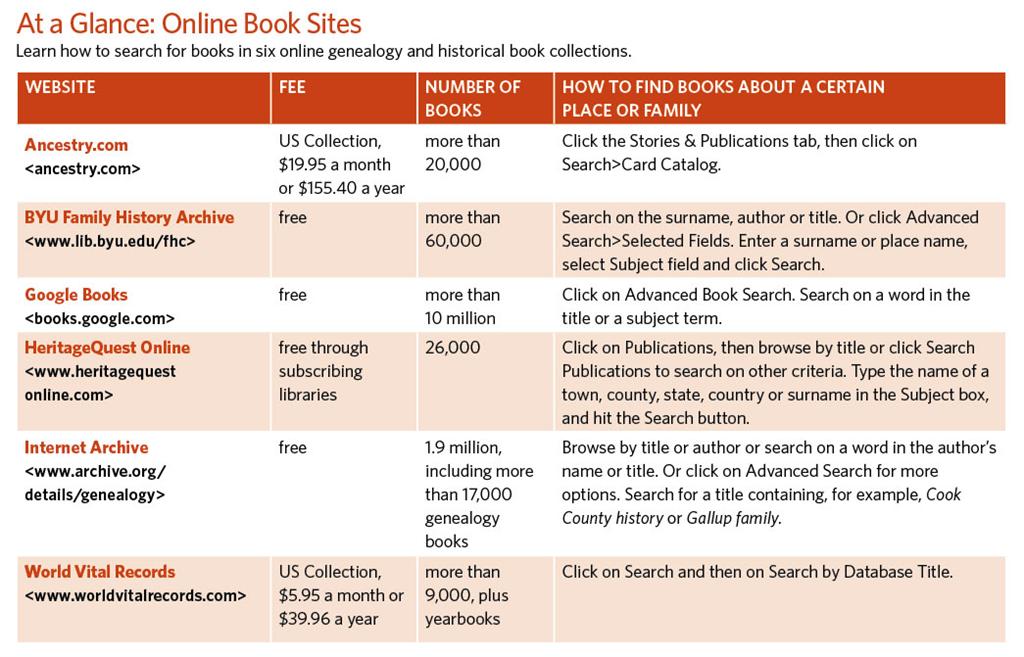

Unless you’re searching for an unusual last name, you should add another term, such as a given name, place of residence or an occupation, to zero in on relevant matches. Here’s how to focus your search in five of the largest online book collections:

Ancestry.com: Click the Stories & Publications tab in the Old Search or restrict your New Search to Stories & Publications to mine books and newspapers. My relative Evan Jones was a missionary to the Cherokee Nation. An exact search for the first name Evan and last name Jones produces thousands of matches in the book collection. Adding the keyword Cherokee pares down the list to 16 matches, plus Member Stories. One of them, a history of the Great Valley Baptist Church in Pennsylvania, tells how Evan and his wife Elizabeth were sent as missionaries to the Cherokee Indians in Tennessee in 1821.Brigham Young University Family History Archive: Go to the site and click on Advanced Search. You must enter something in at least one of the first three boxes to do a search. I entered Evan Jones in the Exact Phrase box and clicked Search. That produced 279 matches, but none of the matches on the first page appeared relevant. Adding Cherokee to the All of the Words box limited the results to eight relevant matches, including a history of Chester County, Pa., that tells about Evan and Elizabeth Jones’s mission to the Cherokee Nation.Google Books: Go to the site; the four main search boxes work the same as the four on the BYU Family History Archive search page. Enter Cherokee in the All of the Words box and Evan Jones in the Exact Phrase box and click the Google Search button. Nearly all of the 680 matches appear relevant. Many are available only in “limited preview,” but some are “full view,” so I can read the entire A Standard History of Oklahoma, which has a photo and biography of Evan’s son Miles.HeritageQuest Online: Most online book collections automatically look for all your search terms near each other. That’s how HeritageQuest Online used to work, but that system was replaced with a much less practical one. Now, words entered in the same search box must appear within four words of each other, but words entered in different search boxes only need to appear in the same book. So if you search on a name and a keyword, you’re likely to get a lot of false matches because many books could have all your search terms. If the surname appears on page 5 and the keyword is on page 250, there’s probably no connection.To get more relevant matches, you can do a proximity search. To find references to the Robertson family of Worcester, NY, enter Robertson NEAR:10 Worcester in the Keywords, Title or Subject search boxes to find the terms within 10 words of each other. If one of your search terms has more than one word, surround it with quotation marks and parentheses to search on the phrase, for example Robertson NEAR:10 (“South Worcester”).World Vital Records: Start on the Advanced Search page to search all databases on World Vital Records. Three generations of my ancestors lived near Dell Rapids, SD. A search on the Family Name Morgan and Place Dell Rapids produces a match in volume two of The Genealogy of the Cleveland and Cleaveland Families. It traces my grandfather’s ancestry all the way back to Moses Cleveland, who settled in Plymouth, Mass., in 1635.Internet Archive: At the site, you can’t search for a surname in a book, but you can find books by author or title. Several years ago, I purchased a copy of A History of Old Tioga Point and Early Athens, Pennsylvania, which mentions some of my immigrant ancestors from Wales. A search on Athens Pennsylvania in the Title box turns up two copies of this book in the Internet Archive, which you can view online or download as a PDF file.

Searches of these online books might miss references to your family, so it’s worth browsing the collections for works about the places and surnames you’re researching. (Many books have their own indexes.) If you find a promising book in a library catalog, be sure to check these online collections before borrowing the book. The chart on page 56 tells you how to search these collections for a specific book or to find town and county histories about the places where your family lived and genealogies covering your family surnames.

Researching your family history online requires close attention to detail, and sometimes you have to alter your search strategy from site to site—but it sure beats the olden days of scrolling microfilm and tracking down rare books.

Tip: When searching for ancestors online, be sure to try alternate spellings, nicknames, abbreviations, foreign equivalents and other variations (such as De Witt and Dewitt). Use Soundex searching and wildcards where available.

Tip: To search for census records on Ancestry.com, skip the home page search box and go to the Search tab, then Census & Voter Lists. If you want to search only a specific census year, click on the US Federal Census Collection link, and then select the census you want from the list of collections and indexes.

Tip: The Family History Library catalog links to books in the Brigham Young University Family History Archive.

More Online

Free Web Content

For Plus Members

Family Tree Shop

From the August 2010 Family Tree Magazine