Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Have you ever heard someone joke about ending up in the poorhouse? In times past, there actually was such a place. It may have been called the almshouse, orphanage, poor farm, county home, workhouse or soldiers’ and sailors’ home. It was where the government gathered and cared for those who couldn’t care for themselves.

Other methods of caring for the poor have been used in the past, too. Local officials sometimes handed out food or fuel, hired local residents to shelter the homeless, or paid for indigent burials. Less-compassionate strategies have included running the poor out of town or forcibly indenturing their children.

Fortunately for us, our ancestors’ misfortune can be our genealogical gain. Governments and organizations often kept detailed paperwork on interactions with the poor. Some of these records survive today, with names, locations, relationships, family circumstances and aid given.

ADVERTISEMENT

Government vital records and censuses didn’t directly ask, “Are you poor?” But hints abound in genealogical records we most commonly consult, as well as often-overlooked resources such as the 1880 special census of “defective, dependent and delinquent” classes. See the box on the next page for ways to gather clues to what your family had—or didn’t—so you’ll know whether to search for them among records of the underprivileged.

As you compile this information, compare it to what you see for other families. Did your relative pay the same in taxes as his neighbors? Did everyone on that census page rent out rooms in their homes? The answers can help you assess relative wealth. Then compare your family’s timeline against economic timelines to see if their finances failed during recessions or panics. You may find explanations for their financial setbacks.

If you find that your family fell on hard times, then it’s time to look to whatever “poor records” may exist for that time period. You may find their names—and details that will stir your compassion—in the records of overseers of the poor, poorhouses, orphan caregivers, the Freedmen’s Bureau and the vast projects of the New Deal.

1. Overseer of the poor records

In Colonial times and the early decades of the United States, officials cared directly for the poor. In places with state-supported churches, this duty may have fallen to church wardens. Eventually superintendents, overseers or trustees of the poor were elected or appointed by county, city, township or town (in New England) governments. Overseers of the poor used a few common strategies, none of them very kind:

• Warning off: Anyone who’d lived in a place less than a year and hadn’t established legal residency (or a “settlement”) might be told to leave. Superintendents escorted transients back to their prior residence or to the state line.

• Binding out: The children of a family deemed too poor to care for them might be forced into an indenture arrangement, often until they reached the age of majority.

• Contracting out: A person unable to care for himself might be placed in the care of relatives, friends or strangers for an agreed-upon sum.

• Auctioning: A jurisdiction might sell care of the poor to the lowest bidder, which often put the vulnerable sick, aged and disabled into the care of the town’s stingiest scrooge.

In some times and places, overseers distributed food, fuel, medicine and funds, especially to the widowed, elderly and disabled. This was called “outdoor relief” because people received it outside of government institutions.

Overseers also might pay for pauper burials in common graves or “potter’s fields,” as charity plots were called.

Trustees of the poor logged who received what aid in minutes or account books. They sometimes created lists of indigent individuals served—and conversely, lists of residents who were delinquent in paying poor taxes. Many poor records name just the head of household, sometimes with a note “and children.” Warnings-off may name where someone was taken. Binding out contracts would name the child being indentured, the person who claimed their care and perhaps more. Relatives who accepted aid to care for their own may be mentioned by name and relationship.

Records of overseers, most commonly found for the 1700s and 1800s, may still be in town halls or county courthouses in a standalone collection, or along with county commissioners’ records. They may also be in a county or state archive or historical society. Some poor records have been microfilmed; run a place search in the FamilySearch online catalog by county or city/town. Look for a poorhouses or poor laws category. The records are likely unindexed, so expect to read through them yourself.

Search online and ask experts at local historical societies and libraries to learn where local potter’s fields were located, and where records, if they still exist, might be kept.

2. Poorhouse records

In the early 1800s, social reformers began to look for more humane ways to care for the poor—and governments looked for cheaper ones. Enter the age of the poorhouse.

The earliest poorhouses were big-city homeless shelters, known as almshouses. Eventually, counties in most states built poorhouses or farms. The idea was to reduce overhead by gathering all the needy in one place and requiring them to work for their own care as much as possible. This institutional care was known as “indoor relief.”

In the early years, the able-bodied poor were housed together with the aged, mentally and physically infirm, families with children and sometimes low-level criminals. In some places, people had to swear a pauper’s oath (an assertion he was without money or property) before a county commissioner to be admitted to a poorhouse. Residents or “inmates” couldn’t leave without permission.

As it became clear that housing criminals with children and the elderly wasn’t the greatest idea, states built children’s homes, hospitals, asylums, and soldiers’ and sailors’ homes. Many of these agencies endured until the early to mid 1900s. Separate “workhouses” housed criminals.

Poorhouse records are among the richest resources on the poor. You may find inmate registers, certificates of indigence, visitors’ logs, medical records, transfers, discharges, deaths and burials. Annual reports may help you understand how many people lived there at any given time, how long they generally stayed, living conditions, daily activities and work required.

If you think your ancestor really did spend time in a poorhouse, first use the internet and local histories to learn which institutions existed and when. Look for poorhouse records with other county records, especially those kept by the county commissioners or overseer of the poor. You may need to widen your search to private, regional and state archives. Once you know the name of the poorhouse and county, enter these as keywords in your web browser and in online finding aids such as ArchiveGrid, a catalog of more than 2 million manuscript records in primarily US repositories. Alternately, court records may point you to an institution: guardianship or commitment papers in orphans’ or probate court records, or criminal convictions in criminal court records.

If a non-governmental organization ran the hospital, settlement home or other institution where your ancestor lived, records likely won’t be in a government archive. Instead, if the organization or a successor exists, contact it directly, or start your search at the county historical society. Keep in mind that privacy restrictions may apply to health-related data, even for people long dead. Find more resources on poorhouses, including a directory of known records by state, at The Poorhouse Story.

3. Orphan records

In the past, children who lost even one parent were considered orphans. Fatherless children with inheritances and “prospects” were assigned male legal guardians by orphans’ and probate courts. These guardians didn’t necessarily care for the children, just for their futures.

But poor children left less of a paper trail, especially when there was no probate process. Legal adoptions were the exception rather than the rule: Most state adoption laws weren’t written until the mid-to-late 1800s. After a parent’s death, look for binding out contracts in probate or orphans’ court records, if they’re not in overseers’ records. Also search for the children in census records and note whether they were employed and how. Look for “missing” children in the homes of relatives, neighbors, friends and possibly remarried parents. Sometimes children (especially very young ones) took new surnames without being legally adopted.

Orphanages became more common during the 1800s. Public ones were outgrowths of the poorhouse system. Private facilities might be run by Catholic orders, Jewish and Christian aid societies and other charities. Sometimes children were placed in an orphanage temporarily or intermittently, and parents or other relatives reclaimed them on remarriage or when conditions at home improved.

Children’s homes generally kept good records of their wards’ personal data and family situations. You might find the child’s name and birthdate, parents’ names, other close relatives’ names, birthplaces and addresses. Date and reason of admission, transfer or placement and discharge may be recorded. Other records may shed light on the home’s rules, daily regimen and attention to schooling and health care.

Some orphanage records survive. Search for them as you would poorhouse records. Learn what children’s homes existed in a place and time using city directories and local histories (look under “charitable societies” or individual churches). For private homes, contact church archives or look for archival collections pertaining to the sponsoring organization. Records of state-run homes and reform schools are likely to be at the state archives or with a state youth agency. Use ArchiveGrid and other online finding aids to locate original records. Keep in mind that records may be restricted for privacy reasons; any requests should include the reason for your request and your relationship to the child. A handful of orphanage records are online at sites such as Ancestry.com.

Between 1854 and 1929, upward of 200,000 homeless New York City kids (not all of them orphaned) were shipped to the Midwest and West. The Children’s Aid Society of New York coordinated efforts among several asylums to identify adoptable children and send them on trains in chaperoned groups. Committees in 45 states, Canada and Mexico vetted prospective parents and paired them with children. Many boys over 10 were apprenticed; most others were adopted.

The Children’s Aid Society kept case files and related paperwork. On the receiving end, county courthouses recorded adoptions and apprenticeships (look in guardianships, deeds and other records). Local newspapers often listed arriving children and their new parents. The placing asylum may be mentioned in paperwork.

Often you’ll know from family lore whether a child arrived on an orphan train. Confirm it by looking for adoptions and apprenticeships. Follow up by researching newspapers and the records of any agency named in adoption papers. Contact the National Orphan Train Complex to access its clearinghouse of information about riders and their family origins. Original records of the Children’s Aid Society, including restricted-access case files, are at the New-York Historical Society. Contact information for other organizations that sent children on orphan trains is at FamilyTreeMagazine.com.

4. Reconstruction-era records

The liberation of 4 million African-Americans from slavery created a displaced and largely undocumented workforce. Freed slaves generally couldn’t read or write, didn’t have surnames, weren’t legally married and had lost contact with close relatives. They needed food, homes, family reunification support, work, job training, transportation, legal aid, medical care and protection in a hostile social environment.

Southern white families also were affected, though less dramatically. Confederate soldiers, many in poor health, returned home to a strangled economy. Plantations lacked workers. Land and goods had been destroyed in battles.

The federal government’s answer to the chaos was the creation of The Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands (the Freedmen’s Bureau). Agents in field offices authorized food, clothing and medical care directly to the poor. Bureau agents also helped African-Americans document marriages and labor contracts, process military benefits claims and prosecute hate crimes. The Bureau established schools and redistributed seized Confederate lands (some back to original owners who signed loyalty oaths).

Freedmen’s Bureau records are rich in information on both Southern whites and blacks. Whites may have been among aid recipients. Records on African-Americans are descriptive, often heartbreaking and may represent the first documentary evidence of ancestors whose prior lives are shrouded in anonymity. Some records even include names of former slaveowners, which illuminates a research path into the documentary darkness of slavery.

The most genealogically meaningful Freedmen’s Bureau documents are records of marriages and bureau field offices. Original records at the National Archives are on microfilm, available through FamilySearch. You can browse the records, with limited keyword searching, on subscription site Ancestry.com. Some have been transcribed at The Freedmen’s Bureau Online.

Subscription website Fold3 has records of the Southern Claims Commission, which document more than 20,000 compensation claims Southerners filed for supplies, livestock and other property seized during the war.

5. Records of the New Deal

Seventy years after the post-Civil War chaos, the United States found itself in economic crisis during the Great Depression. Nationwide, one in four people was out of work—more than double most state unemployment figures in recent decades. President Franklin D. Roosevelt led the creation of organizations to put people to work, including:

• Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC, 1933-1942): This program employed 2.5 million young men and veterans to work on conservation projects in six- to 24-month stints. Workers lived in CCC camps, where housing, food, medical care and social life were provided in addition to work. About 75 percent of their pay went to a parent or other designated beneficiary back home.

• Works Projects Administration (WPA, 1935-1943): Originally called the Works Progress Administration, the WPA provided nearly 8 million jobs building roads and dams, painting murals, inventorying historical records, conducting oral history interviews and more. Jobs often matched skill sets and were close to home. Most workers had to reapply after 18 months to continue WPA work.

• National Youth Administration (NYA, 1935-1943): Those aged 16 to 24 could work part-time while going to school or receiving job training. The NYA offered health care, life skills classes and social activities. African-American youth were intended to be fully included in the program, but some officials segregated workers and offered different opportunities.

Did your relative participate in the CCC, WPA or NYA? Maybe family stories say Granddad did the ironwork at a local zoo or helped build the Hoover Dam. Documents created during the New Deal era—letters, address books, government records, directories and more—may give the address of a CCC or WPA work camp. The genealogist’s most common clue, however, is the 1940 census. Question 22 asks whether the person did “public Emergency Work (WPA, NYA, CCC, etc.)” during the week of March 24-30 that year. It doesn’t capture every worker who participated over the full decade these programs ran, but it’s just one more clue.

The government kept personnel records on its relief workers. CCC enrollees have the most detailed files, with name, date and place of birth, a physical description, citizenship/naturalization status, job assignments, payroll and beneficiary information, and admission/discharge dates. Sometimes they mention education, military service, job history, health profiles, medical records and disciplinary actions. WPA and NYA personnel records aren’t as detailed, but they do include assignments, wages and dates of employment. Some describe the family’s resources.

Order personnel files from the National Archives’ National Personnel Records Center. Click Archival Civilian Personnel Records for order forms and instructions. Include plenty of details if you order copies: full names, parents’ names, date and place of birth, home address, and anything you know about the person’s service, such as when and where they worked.

Credit Report

These records provide clues to the state of your ancestors’ wealth (or lack of it):

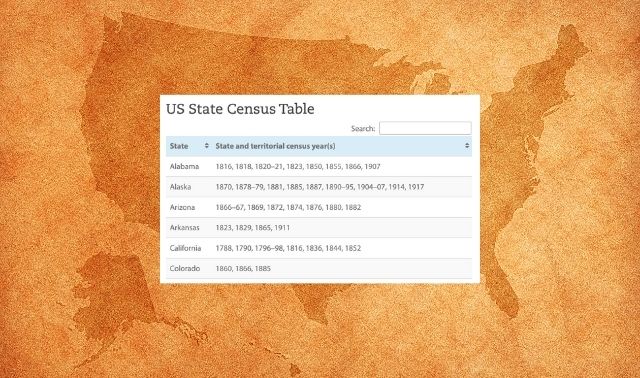

• Federal censuses: Beginning in 1850, US censuses ask about real estate owned; the 1860 and 1870 counts add a column for personal property value (including slaves in 1860). Useful questions about occupation and employment status begin in 1850 and 1880, respectively. You’ll find out at whether a family rented or owned its dwelling place beginning in 1900, and even meatier financial details in later enumerations: amount paid for rent/mortgage, number of weeks out of work, etc. Finally, if you find a census listing of a relative residing in an institution, research the name to see if it’s a poorhouse or similar institution.

• Special censuses: Various supplemental censuses taken at the same time as the regular census hold clues to financial status. Agricultural and industrial or manufacturing schedules for 1850 through 1880 valuate individual farms, as well as businesses with annual gross production over $500. Schedules aren’t available for every decade and place, but you’ll find many online at Ancestry.com. That site also has many states’ 1880 schedules of “defective, dependent and delinquent” individuals (called DDD schedules). Other states’ schedules are in a variety of archives; download a list at FamilyTreeMagazine.com.

• Real estate and personal property tax records: These often itemized taxable goods. Relatives who weren’t taxed weren’t necessarily poor, but it’s a possibility. Look for city, county and state taxes at government archives, on microfilm through FamilySearch or in online databases (the free FamilySearch.org has Ohio, Texas and the city of Boston, for example). Federal direct tax records exist for some states for 1798 (the “window tax”), the Civil War era and beyond; Ancestry.com has Pennsylvania’s 1798 tax list and more than 8 million IRS records from 1861 to 1918.

Searching for Poorhouse Records

Panics and Depressions Timeline

- Panic of 1797: The country’s first major economic crisis was caused by the bursting of a land speculation bubble, among other factors.

- Depression of 1807: English trade restrictions and the Embargo Act of 1807 led to a three-year depression.

- 1815-1821 depression: War of 1812 debts and land speculation led borrowers to default and banks to fail.

- Panic of 1837: Another land speculation bubble burst and led to the failure of 40 percent of US banks.

- Panic of 1857: A recession caused by gold-fueled inflation led to a panic when the New York branch of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Co. failed.

- Panic of 1873: A railroad bust followed several years of slow economic growth.

- Panic of 1893: The Philadelphia and Reading railroad bankruptcy set off a bank run. More than 15,000 businesses eventually failed.

- Panic of 1907: An attempt to corner the copper industry led one of the nation’s largest trust companies to fail, starting a chain reaction.

- Depression of 1920-21: A short, severe depression was caused by post-WWI deflation and increased unemployment as troops returned home.

- The Great Depression: The stock market lost more than a quarter of its value in the Black Tuesday stock market crash Oct. 29, 1929. Unemployment reached 25 percent and economic production was cut in half in the nearly 12-year depression.

More online

• Research a CCC worker

• WPA oral histories

• Where to look for DDD schedules download

• WPA historical records survey

• Finding financial records

• US panics and depressions

ADVERTISEMENT