What’s the Best DNA Test Choice?

Q: My surname is Blanchard. I’ve traced my paternal line back to David Blanchard, born in 1822 in Vermont, but I reach a brick wall at his parents. I’m working with a professional researcher to find records to trace my paternal line, but should I also pursue DNA testing? If so, would it be better to use Y-DNA (I’m male) or autosomal DNA?

A: There’s never a guarantee that a particular historical record will solve a genealogical mystery. The only way to know whether a resource could help is to identify the record types that might hold answers, find the documents relevant to your family, and analyze their content. Sometimes they’ll shed light on the question; sometimes they won’t.

The same is true of DNA testing, which in the past several years has become an essential “record type” for genealogists. Because DNA is a record type that might be helpful in this particular scenario, you should pursue it if at all possible. The question, therefore, is whether Y-DNA, autosomal DNA (atDNA) or both types of tests should be used. (Note that there’s no need to consider mitochondrial DNA testing because this type of DNA reflects only maternal lines.)

How Y-DNA Can Help Ancestral Research

When a brick wall involves the direct paternal line, you should always consider Y-DNA as a potentially relevant record type. Because your working hypothesis is that you inherited both your surname and your Y-DNA from David Blanchard, finding others with similar Y-DNA might help you identify the correct Blanchard family within which to search for David’s ancestors.

The likelihood that a Y-DNA test will provide clues depends on many factors. An important one is whether other people related to you on your paternal line have tested their Y-DNA. A quick online search for a Y-DNA surname project (enter “Blanchard surname project”) will determine whether others have tested. If there’s a surname project with numerous participants, you’re more likely to find clues that’ll benefit your research. Once again, however, there’s no guarantee that Y-DNA testing will lead to clues.

Another factor to consider, especially if you don’t find a surname project, is whether you have any “candidate ancestors” for David Blanchard—people you think may be his father or grandfather—and if those candidates have any paternal-line descendants with whom you could compare your Y-DNA. This would require you to research each candidate’s family forward in time, in hopes of finding an appropriate person to test.

The Limitations of Y-DNA

As with any genealogy record, it’s important to remember the limitations of Y-DNA testing. There is currently no Y-DNA test that can determine whether two people are brothers, cousins or some other close paternal relationship. As a result, finding a Blanchard who shares your Y-DNA means that you’re paternally related.

But you can determine the exact nature of that relationship only by combining the DNA record with other genealogy research. Additionally, remember that the David Blanchard you’ve found may not have been biologically a Blanchard. He may have been adopted or changed his name, among other possibilities.

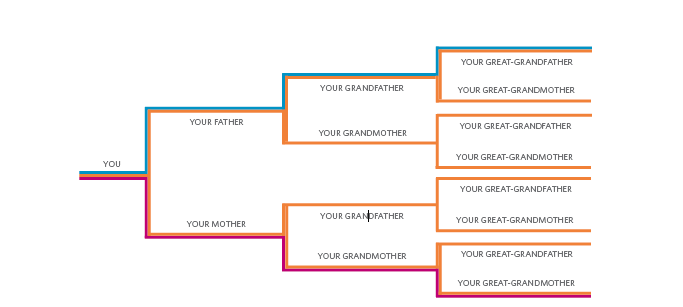

Because Y-DNA is passed down relatively unchanged from father to son, a Y-DNA test informs you about the test-taker’s male line (shown above in blue). A man should have the same Y-DNA as his father, father’s father and brother, the brother’s son, father’s father’s father and brother, and so on. An atDNA test, on the other hand, informs you about all the test-taker’s ancestors (shown in orange) for up to five or six generations. (The red line shows the inheritance of mitochondrial DNA.)

How Autosomal DNA Can Help Ancestral Research

AtDNA can be another important record type in a scenario like yours, depending on the number of generations between you and David Blanchard. The greater the generational distance, the less likely it is that autosomal DNA is a potentially relevant record type.

You’d be using autosomal DNA to look for relatives of David Blanchard’s unknown parents. David Blanchard’s birth year of 1822 means he’s likely about your third-great-grandparent or so, which would make his parents your fourth-great-grandparents. Any cousins related to you through David Blanchard’s parents would be at least fifth cousins. Unfortunately, you share only a very small amount of DNA with a fourth-great-grandparent, about 1.56 percent on average. And, not surprisingly, the chances that you share DNA with a fifth cousin are relatively low.

So your likelihood of randomly matching a fifth cousin descended from David Blanchard’s unknown parents is low. The likelihood is still significantly higher than “not at all,” though, so you should at least consider an atDNA test. If the unknown ancestors were more distant, your determination of whether to use autosomal DNA would likely change.

Because you and your siblings, if you have any, inherited different parts of your father’s atDNA, testing your siblings could increase your chances of finding a match. Testing cousins who are David Blanchard descendants also could turn up promising matches you don’t have. Of course, it’s possible an atDNA test result could lead you to previously unknown cousins who are descended from David Blanchard, and those cousins might have the answers you’re looking for about his parents.

One way to increase your probability of finding relevant atDNA matches is to do targeted DNA testing. For example, if David Blanchard has known siblings, testing descendants of those siblings could uncover additional segments of DNA inherited from the unknown parents, thus increasing the likelihood of finding cousins related through those unknown parents.

Similarly to Y-DNA, if you have candidates for David Blanchard’s parents, testing the atDNA of descendants of those candidates could identify them as cousins. AtDNA also has its limitations: Sharing DNA with one of these fifth cousins doesn’t prove the hypothesized relationship—you could be related to the person through some other shared ancestor. But the match is a piece of evidence that you can analyze together with other evidence.

A version of this article appeared in the September 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine.