Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Sometimes your DNA matches don’t quite match what you expected. Maybe you and your mom don’t have all the DNA matches you expected, or you can’t find a particular surname among your matches. Expert Diahan Southard breaks down why this might be the case—and what to do if a relative isn’t actually related to you like you thought they were.

Parents and Shared Matches

Q: My mom and I have both tested with AncestryDNA. Should she be a shared match for all my matches from her side of the family, because I received all that DNA from her? I have hundreds of matches, and she and I share only 12 of them. I thought things would be more equal between the two sides of my family.

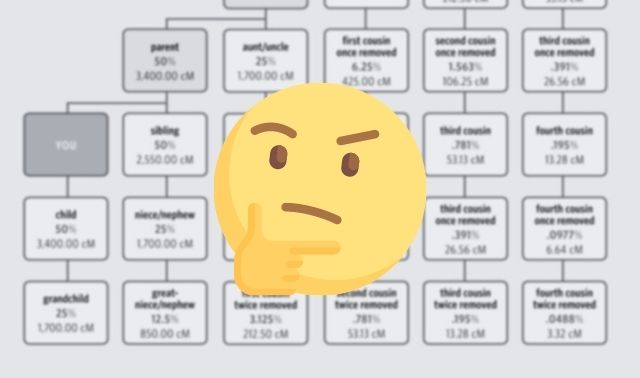

A: Because of the way autosomal DNA is inherited—you get half of your DNA from your mom and half from your dad—every person on your match list should match one of your parents if your parents have been tested. But there are a few reasons why your match page might not look like you’d expect:

If you’re using the Shared Matches tool, which displays matches who share DNA with you and another person (in this case, your mom), remember that AncestryDNA shows you only shared matches who are related to both you and your mom as a fourth cousin or closer. So all those more-distant cousins won’t show up on that shared matches list.

If your dad’s side of the family is significantly larger than your mom’s—or, for some reason, a lot of people from his side are testing their DNA—you’ll probably see more matches from that side. If possible, test your dad or a close relative of his to shed more light on the close cousin matches you don’t share with mom.

If a branch of your family arrived in the United States relatively recently, their DNA is less likely to appear in a genetic genealogy database. Currently, due to database demographics—mostly Americans descended from European immigrants—test-takers whose families are recent immigrants or have roots outside Europe will have fewer matches than test-takers whose families have been in the United States for generations. This will change as the diversity of DNA databases grows.

Every so often, “ghost matches” crop up as distant cousins, causing you to have matches that don’t seem to come from either parent. But these matches are a result of DNA rearranging, instead of shared ancestors.

You actually have two copies of each bit of DNA, one from Mom and one from Dad. But when testing companies look at your DNA, all they see initially is a big pile of values. They don’t know which bits go together. The process of figuring that all out is called phasing.

This illustration shows a simplified example of how a phasing error could happen. Each word is like a bit of your DNA that’s being analyzed. In section A, your mom and dad each have a sentence that makes sense. You carry around these two sentences in your DNA. But when the testing company analyzes your data at each of the colored locations, the words have the chance to be mixed up, as you can see in section B.

Some mixups wouldn’t make all that much difference: Switching the words favorite and best doesn’t significantly impact the meaning of either sentence. But what if we switched some other words, as in section C? The new sentence makes a big difference, especially to the mom. DNA testing companies do have double-checks in place to help prevent this situation, but mistakes occasionally happen. These errors don’t appear in close relationships, though.

When something doesn’t make sense like this, you can always ask for help in the Ancestry Support Center. Click Support Center at the bottom of the AncestryDNA site, then DNA.

A version of this Q&A appeared in the May/June 2017 Family Tree Magazine.

Surnames “Missing” From Matches

Q: I am really puzzled. My father submitted his DNA to Ancestry, and I did too. I have many shared matches with him. But, my mother is deceased so there is no DNA from her. I have many DNA matches from her maternal side, but I am not finding one person with her father’s surname of Forbish. Does this mean he was not her biological father? Thank you for any light you can shed on this predicament.

A: Many genealogists are taking ahold of the idea that testing more known family members gives you test results that are better able to help in solving family history questions. And while this is entirely true, it can sometimes just produce more data that we have to try to search through.

You are correct in that, as soon as you have one known family member tested, you have a clue that can help you identify at least which branch of your tree some of your unknown branches might belong to. We do this primarily by using the Shared Matches tool.

Let’s say your known first cousin, Ralph, has DNA tested. You and Ralph share paternal grandparents Marcus and Hilda. That means that anyone else who is sharing DNA with you and Ralph should also be related to Marcus and Hilda in some way. So you can go through your DNA match list and mark those particular matches as paternal side, even if you don’t quite know how they connect. It sounds like this is exactly what you have done with both your paternal and maternal side cousins who have tested.

My first follow-up question for a missing surname would be “Do you have any first cousins on your mom’s side tested?” If you do, then we can look at the total amount of shared DNA with that first cousin to make sure you are full first cousins, as opposed to half first cousins (which would indicate that your mom was just a half-sibling to your aunt or uncle). Without a direct test of your relationship like that, we can only be left with speculation.

However, we might be able to turn speculation into something more if you have a close match that you know is not related on your dad’s side (not sharing any DNA with your paternal cousins) and doesn’t seem to be related on your mom’s side (not sharing DNA with your known maternal cousins). If you have someone like that in your match list, it is time to investigate.

A close match, meaning a second cousin or closer, who doesn’t seem to match anyone else, could represent a great grandparent couple that was previously unknown to you.

If you do not have a match like this, but you still don’t see the missing surname in your match list, it could just be that no one from that branch of your tree has tested yet. This is often the case if your line has recently immigrated into the United States. Your best course of action moving forward is to directly test someone you know is related to this Forbish line, and then analyze the results.

Q&A last updated, October 2020.

Unexpected Relatives

Q: My DNA results say that a “relative” of mine isn’t actually related by blood. My parent/grandparent/sibling/aunt/uncle/cousin isn’t who I thought they were. What do I do now?

A: I hear you. This situation can be even more alarming if you were the one who asked the relative to test in the first place. That is why I am constantly recommending that—before you ask your relative to test—you give them a quick primer on what they can expect, and ask for their preferences on how much they want to know about the results of the test.

In your quick primer on the possible outcomes of DNA testing, let them know that many people find unexpected results. This is everything from not having the Italian ethnicity percentage they expected to finding they have a half-sibling they did not know about. There’s also the possibility that they themselves do not biologically match their parents or siblings.

Sometimes we are so anxious to get that older uncle or cousin’s DNA into the database that we skip over these important details. We don’t need to scare them, but we do need to inform them. Simply saying something like “Hey Uncle Mike, I want you to take this DNA test so we can find out more about your great-grandfather. But along with that, we will be able to see your relationships to anyone else in the database who has taken a DNA test. This might mean we find relatives we don’t even know about yet.”

After your quick primer, ask Uncle Mike how much he wants to know about the outcome of your research. First, ask if he wants to know if you uncover anything about his great-grandfather. Then ask specifically if he wants to know if you find out anything unexpected about his family relationships. You may even want to have this in writing, so the whole family is clear about what Uncle Mike wants, should any disagreements arise.

Ifyou weren’t that proactive to find out what Uncle Mike wanted beforehand—and you find yourself with unexpected information about his connection to the family—it can be difficult to know how to proceed. And unfortunately, there are no clearly defined protocols here.

The very first thing you need to do is be absolutely certain you have interpreted the genetic data correctly. There is nothing worse than making assumptions and causing a hullabaloo only to discover that you were in error.

I learned from my dear friend Blaine Bettinger that, in this situation, there are four main characters:

- The Discoverer (you)

- The Subject (the person about whom a familial revelation was made; for example, Uncle Mike, if you discovered he is not the child of the man he grew up with)

- The Secret Keeper (the person who likely knew about the discrepancy but said nothing; in this case, likely Uncle Mike’s mom)

- The Affected (the rest of the family)

Whenever possible, you should allow the Secret Keeper to talk to The Subject directly. So, if your grandmother is available, you should approach her and allow her the opportunity to talk to Uncle Mike privately. If not, you are likely left to simply follow the Golden Rule and do unto others as you would want done for you. And certainly keep in mind that family is bigger than biology.

Q&A last updated, October 2020.