Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Q: I’ve had autosomal DNA testing done for my father, mother, wife and myself. We’re awaiting the results for my brother’s test. I transferred the Ancestry DNA results to GEDmatch and Family Tree DNA. Whom should I test next?

A: Remember that the autosomal DNA test traces both sides of the family tree and is helpful in tracing the most recent five or six generations of the test-taker’s ancestry. The more distant an ancestor, the less of that person’s autosomal DNA you have, until he or she “drops off” your genetic family tree.

The most basic rule in autosomal DNA testing is to test any relative who doesn’t have both parents living. But since most of us don’t have the financial resources this approach might require, a testing plan also should take into consideration the reasons for pursuing genetic genealogy. More often than not, test-takers are looking at one (or both) of two situations:

- They’re trying to solve a family history mystery.

- They just want to see what they can find out.

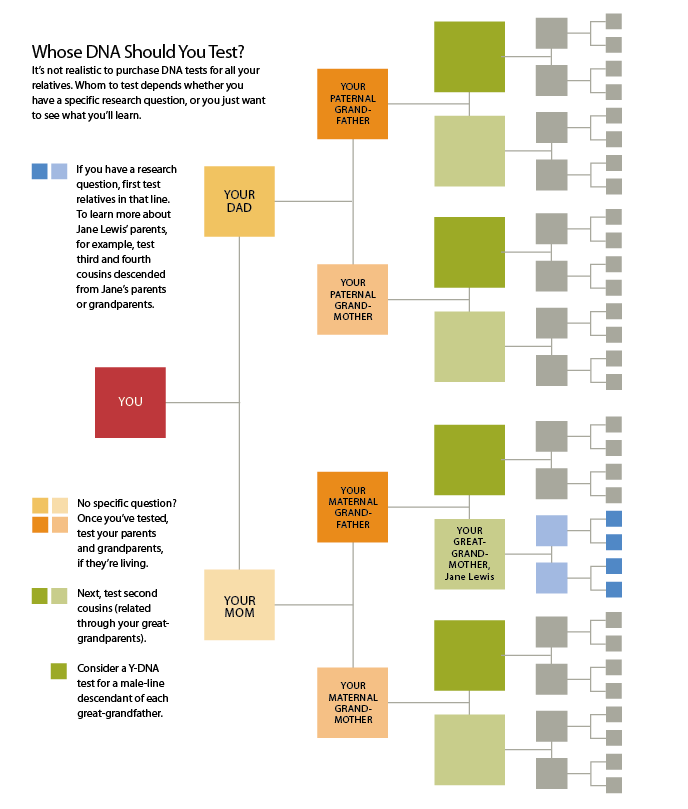

If you have a family mystery, you should create a testing plan that’ll maximize your chances of finding out more about the ancestor in question. Let’s say you’re trying to find the parents of your mom’s dad’s mom—your great-grandmother—Jane Lewis. You carry about 12 percent of Jane’s DNA (you have 50 percent of your mom’s DNA and 25 percent of your grandpa’s), and only about 6 percent of the DNA of each of her parents, the people you’re trying to find. So if you want to know more about Jane and her parents using DNA, you need more DNA. Testing any of Jane’s descendants is helpful. But most helpful will be testing your second cousins, people who are descended from your grandfather’s siblings. These siblings got different parts of Jane’s DNA than your grandfather did, and passed some of those parts down to their children and grandchildren.

Testing a second cousin not only lets you capture more of Jane’s DNA, it also lets you differentiate the DNA you received from Jane (and her husband; we can’t separate the two at this point) and the DNA you received from your seven other great-grandparent couples. You can do this by studying the other matches you share with your cousins using these tools offered by your testing company:

- 23andMe: Relatives in Common

- AncestryDNA: Shared Matches

- Family Tree DNA: In Common With

- MyHeritage DNA: Shared DNA Matches

In that list of shared matches, look for third cousins who might be related to Jane’s parents (shown in light blue on the opposite page) or fourth cousins who might be related to Jane’s grandparents (shown in dark blue).

If you’re testing not to address a particular hole in your tree, but just to document your family line, see what you can find out, or just because it looks interesting, try this strategy: Gather your second cousins from each of your known ancestral lines at the great grandparent level (shown in green). You should also consider finding a direct paternal line descendant of each of your four great-grandfathers (shown in dark green) to take a Y-DNA test, which would represent the surnames of each of those lines. The Y-DNA record for these paternal lines can help you sort out how other lineages with the same (or similar) surnames are related, among other questions.

So keep recruiting those relatives to be tested. The more you know, the more you’ll be able to learn.