Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

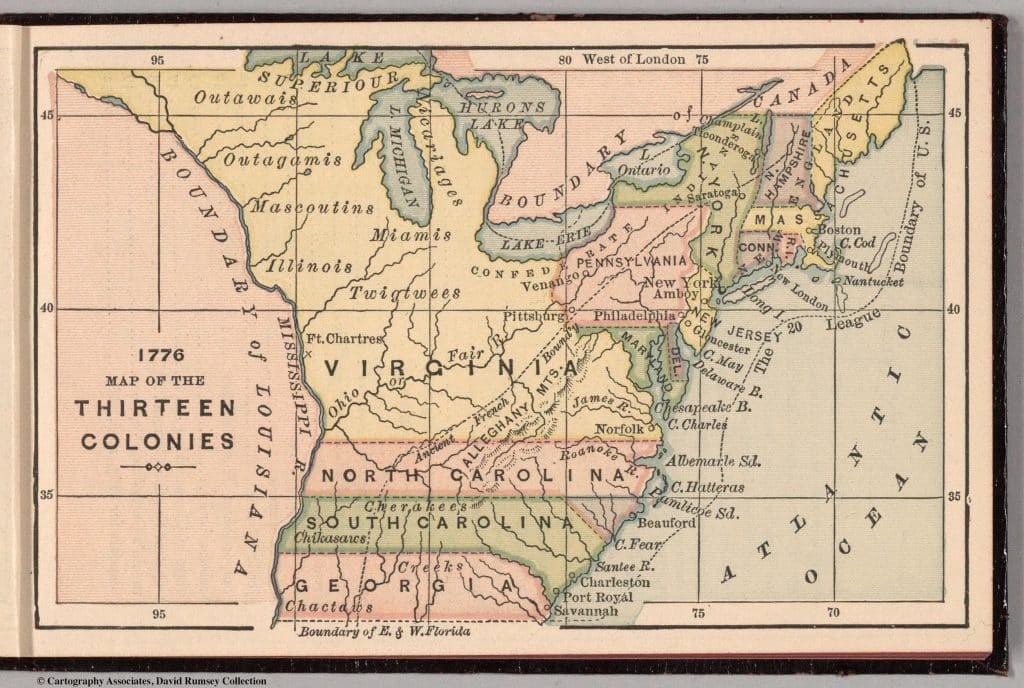

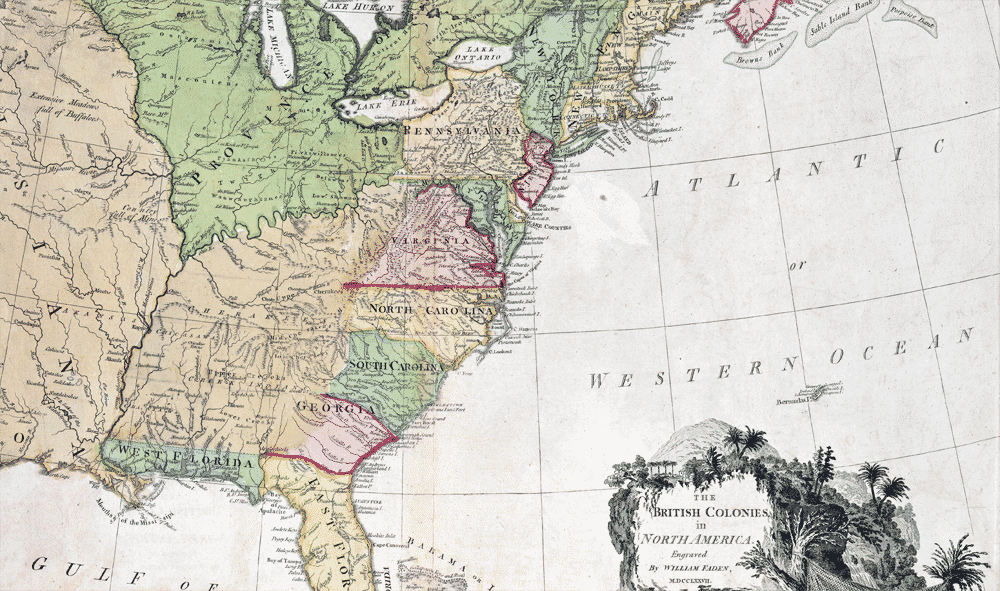

It’s easy to forget that the United States’ Colonial history spans almost 170 years before the Revolutionary War. In fact, the years of post-Colonial US history didn’t surpass those of the Colonial era until the Truman administration (1945–1953).

If you have deep roots in the United States, you likely have ancestors who lived in the often-overlooked time period between the founding of Jamestown (1607) and the Battles of Lexington and Concord (1775). Fortunately, researching their lives in Colonial America has never been easier.

Whether they were among the earliest colonists—at Jamestown or Plymouth—or came later to less-storied destinations, your pre-Revolution ancestors live on in a boatload of online resources. Many records once accessible only on microfilm or dusty library shelves have been digitized. And you can still access records that are offline by borrowing them with help from the globe-spanning library database WorldCat.

What follow are key record groups to research if your ancestors were among those who arrived in the United States between the early 1600s and the American Revolution.

Research Their Arrival

If your ancestors arrived via the storied Mayflower in 1620, you can look for them in the Jamestowne Society Lineage Paper Project or the Mayflower Society’s Lineage Match. FamilySearch also has a collection of Mayflower descendants, and visitors to Plymouth can check out The Mayflower Society’s genealogy research library.

Of course, most colonists didn’t arrive on those early ships: the Mayflower in Plymouth, or the Susan Constant, Godspeed, or Discovery in Jamestown. The best source for researching Colonial arrivals is Filby’s Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, available in many major libraries or online at Ancestry.com. And the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild hosts many volunteer-transcribed passenger lists.

The Great Migration Study project aims to profile the 20,000 English colonists who settled in New England between 1620 and 1640, making it a great resource for that region. It’s available in print, at the American Ancestors site and at Ancestry.com.

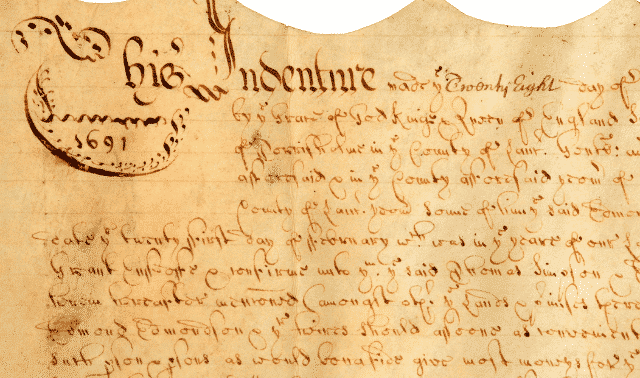

If you think an ancestor came as an indentured servant, check out our research guide. You can start with Peter Wilson Coldham’s The Complete Book of Emigrants in Bondage, 1614–1775, and Emigrants in Chains, 1607–1776; both volumes are published by Genealogical Publishing Company and searchable at Ancestry.com. Ancestry.com also has a collection of Virginia apprentices.

Your Colonial ancestors who came to the United States enslaved present an entirely different research challenge. Our guide to getting started with African American research can help.

Find Available Censuses and Substitutes

Decennial censuses at the federal level didn’t begin until 1790, when they were first mandated by the Constitution. But most colonies created some sort of census or tax list that can serve as a substitute. Many have been collected and reconstructed by Census Publishing, resulting in an Ancestry.com collection “U.S., Census Reconstructed Records, 1660–1820.”

Online coverage of individual colonial censuses and tax lists is otherwise spotty. Extant enumerations have, however, been microfilmed and/or transcribed in print, available at the FamilySearch Library and through WorldCat by searching the colony’s name plus census.

Many early censuses and substitutes were published, and are available online through Ancestry.com, books or on archival websites:

- Connecticut conducted censuses in 1756 and 1762, and a 1670 enumeration has been reconstructed from various records. The 1756 and 1762 counts are not searchable online, but the 1670 reconstruction has been digitized on FamilySearch as part of The Wyllys Papers: Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society, volume 21.

- Delaware: In addition to various early censuses and tax records collected in Early Delaware Census Records, 1665–1697 (Accelerated Indexing Systems), Delaware has a 1693 census of Swedes in the area, hearkening back to its early years as a Swedish colony.

- Maryland entered the Revolution with a 1776 enumeration, an index of which is available at the Maryland State Archives.

- New Hampshire conducted censuses in 1732 and 1776, and a census substitute, New Hampshire Residents, 1633–1699, is available in print (Holbrook Research Institute).

- New Jersey conducted four colonial censuses, but none survive. Try instead New Jersey Tax Lists, 1772–1822 (Accelerated Indexing Systems), included in a census substitutes index on Ancestry.com.

- New York conducted censuses beginning in 1663, but some have been lost. Surviving enumerations are found in Early New York State Census Records, 1663–1772 (RAM Publishers).

- Rhode Island researchers are perhaps the luckiest, with censuses in 1730, 1747 to 1755, 1774 and 1776.

- Virginia’s 1624 and 1625 censuses have been published in part in Adventurers of Purse and Person, Virginia, 1607–1624/5 (Genealogical Publishing Company). Reconstructed Virginia censuses have been published for 1720, 1740 and 1760 (TLC Genealogy).

Tax lists and other compilations can serve as substitutes in colonies that didn’t conduct actual censuses:

- Georgia: A List of the Early Settlers of Georgia (Genealogical Publishing), searchable on Ancestry.com, logs Georgia settlers from 1732 to 1741.

- Massachusetts: Colonists can be found in a 1771 tax list.

- North Carolina: Tax lists as early as the 1680s have been compiled in Early North Carolina (Accelerated Indexing Systems).

- Pennsylvania: Various tax lists and land records can substitute, such as Secretary of the Land Office Rent Rolls, 1703–1744 and The Pennsylvania Archives.

- South Carolina: Researchers can consult Citizens and Immigrants: South Carolina, 1768 (Heritage Papers).

Search for Vital Records

Since many states didn’t start keeping official vital records until a century or more after independence, it’s no surprise that Colonial-era vital records are hit-and-miss.

New England researchers, however, can take advantage of a wealth of vital records kept at the town level. The subscription site American Ancestors and FamilySearch holds several sets of microfilmed New England records.

New England records typically start about 1630 to 1640 for births and christenings, with deaths and marriages coming somewhat later. Massachusetts records at FamilySearch, for example, date from 1639 for births and 1695 for marriages, but the death collection’s earliest coverage is 1795. Don’t overlook separate collections of town records.

Those with Colonial kin outside New England should still give FamilySearch a try. The “Virginia Births and Christenings, 1584–1917” collection, for example, has more than 1.5 million records, and those from Colonial years often also include death data. New York births and christenings can be found back to 1640 and marriages from 1686.

New Jersey was among the earliest adopters of official vital records—requiring town clerks to keep track of marriages, for example, in 1673. Compliance was spotty, but enough New Jerseyites created vital records to merit FamilySearch collections of births and christenings beginning in 1660, marriages from 1678, and deaths and burials from 1720.

Don’t overlook less-conventional sources of vital records, such as those abstracted from newspaper notices and cemetery records. Connecticut’s Charles R. Hale Collection, available on FamilySearch, covers more than 1.2 million records beginning in 1640.

Ancestry.com subscribers can find colonial vital records—many from the same sources—using the card catalog. Wider collections of note here include “American Marriages Before 1699” and “New England Marriages Prior to 1700.”

Vital-record seekers for a few colonies, notably in the South, will strike out in one or more categories, wherever they look. Georgia and South Carolina, for example, lack any death records from Colonial days.

Explore Church Records

In the Colonial era, church records are often intermingled with those from government sources. New England, again, is especially rich in church records: American Ancestors has dozens of colonial church records for individual churches as well as cities and towns. You can search, for example, records from the First Church in Plymouth, from 1620 on, or a collection of Boston church records starting in 1630.

Certain individual churches also excelled in early record-keeping. In Connecticut, the Congregational church was the official state church until 1818, and many of its records dating back to 1630 have been indexed and/or digitized. See the state library’s guide and searchable collections on FamilySearch and Ancestry.com.

The Society of Friends, popularly known as the Quakers, kept detailed records that are especially valuable to researchers in Pennsylvania (founded by Quaker leader William Penn). If your Quaker ancestors branched out from there to other colonies, these are also worth a look.

The FamilySearch Library has microfilmed indexes to Quaker meeting records by William Wade Hinshaw for Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Some of these (along with later meeting records from several other states) can be searched online at Ancestry.com. The six-volume Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, with entries as early as 1607, is also searchable on Ancestry.com.

The Dutch Reformed Church, most prominent in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, was another early adopter of detailed record-keeping. Ancestry.com has two collections of Colonial-era Dutch Reformed records, covering both vital records and church membership. Presbyterian vital and membership records are available in another Ancestry.com collection, dating from 1701.

To see what other church records might help your Colonial quest, try the card catalogs of sites such as American Ancestors, FamilySearch, Ancestry.com and Findmypast.

Mine Land Records for Clues

Though scant on basic genealogical data, colonial land records can establish when and where an ancestor lived, and often contain clues to relationships.

Many colonies granted land to settlers as “patents,” documents that have been widely microfilmed and digitized. This was often done using the headright system, in which settlers were granted a certain amount of land for every person transported there.

Virginia land grants beginning in 1623 are collected in five volumes of Cavaliers and Pioneers, accessible at the Library of Virginia, the HathiTrust online library and Ancestry.com. Abstracts of land grants in the “Northern Neck” of Virginia are also available in multiple volumes on Ancestry.com.

Land in the Carolinas was granted either by one of the Lords Proprietors or (later) directly by the British crown. The Granville District in northern North Carolina remained under the “proprietorship” of the Earl of Granville until his death in 1763. South Carolina land warrants from 1672 to 1711 can be found in an e-book on FamilySearch or three collections on Ancestry.com. More than 1 million images of some 217,000 North Carolina land grants from 1663 on can be searched at www.nclandgrants.com (free registration).

In Colonial Maryland, the “proprietors” who issued headrights from 1633 to 1683 were the Calvert family. Records of land grants as well as later transactions have been indexed in The New Early Settlers of Maryland and on Ancestry.com.

Beginning in 1676, what we now know as New Jersey was divided into two provinces, East and West Jersey. Fortunately, the state archives have united land records from the two provinces, along with earlier records beginning in 1650 online. Ancestry.com also has a collection of New Jersey patents and deeds, 1664 to 1703.

Other colonies handled property records in ways more familiar to modern researchers: deeds transferred between individuals. To find land records from your ancestor’s colony in the FamilySearch Catalog, do a place search for the name of the state, then scroll down to “Land and Property.”

Some of these transcribed or microfilmed records have also been digitized, though are not always searchable. Massachusetts land records from 1620 are merely browsable online at FamilySearch, for example. You can find searchable collections by clicking Search > Records, then typing a state name under Search by Place, clicking the state name, and clicking See All [State] Collections.

Search Court and Probate Records

Those same steps can lead you to FamilySearch’s court and probate records, where they’re grouped as “Court, Land and Wills.” (In the FamilySearch Catalog, they’re separated into sections for “Court Records” and “Probate Records.”)

FamilySearch has digitized collections of wills and other estate papers dating to Colonial times, including from: Georgia, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and South Carolina. Most of these, however, are not searchable and must be browsed, typically first by county and then by type (such as wills) and year. Likewise, Ancestry.com has searchable collections of wills and other probate records, mostly beginning in the 1600s, for all 13 original colonies plus Maine (which was then part of Massachusetts). Note that, on both sites, the Georgia collections don’t begin until 1742. Check also for county-level collections, in addition to the statewide ones.

New England researchers should check American Ancestors for court and probate records for individual counties and towns. And Virginia researchers can find indexed estate-administration records from will books in that state dating from 1633 at the Library of Virginia.

USGenWeb and the USGenWeb Archives include many wills and other court records transcribed by volunteers. Some date from Colonial times.

Additional Records

Military Records

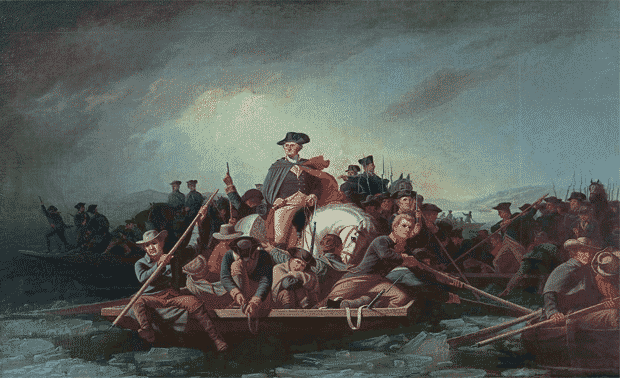

Even before the Revolutionary War, colonists joined militias and fought in a variety of conflicts, most notably the French and Indian War. Militia lists and muster rolls can establish an ancestor’s residence as well as details about his life. These are most widely available for Virginia (two collections are on Ancestry.com) and North Carolina (see the detailed site Military Organizations in Colonial North Carolina). Early histories of each colony also often contain lists of militia members.

Family Bibles

Bible records can substitute for vital records in Colonial times. The Daughters of the American Revolution site, though focused on ancestors from 1776 on, has more than 84,000 searchable Bible records, many of them beginning pre-Revolution. The Library of Virginia and the Connecticut State Library each have collections for their respective states.

Newspapers

Even in Colonial times, newspapers can also be a surprisingly helpful source. The best-known example is probably Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette, which began publication in 1728. (The FamilySearch Library has microfilmed abstracts and indexes.) The subscription site GenealogyBank, which specializes in newspapers, includes publications from as early as 1690.

Papers

Collections of documents from Colonial times can also provide clues. Find Virginia papers and Colonial records dating to founding in 1607 at FamilySearch and Ancestry.com, as well as the Library of Virginia’s Colonial Papers collection.

Biographies

Though not as well-known as the DAR, the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America serves a similar function for Colonial times. You can search the society’s Ancestor Biographies at www.nscda.org/historical-activities/ancestor-biographies. Ancestry.com also has two digitized publications: Genealogical Guide to the Early Settlers of America by Henry Whittemore (Clearfield Company) and Colonial Families of the USA, 1607–1775 (Genealogical Publishing).

Problems in Colonial Research

The very nature of life in Colonial America—small settlements that spread inland from the coast—presents special challenges for family-history researchers.

For one thing, given the relatively small and geographically concentrated population of Colonial times, your ancestral families will interconnect, sometimes in confusing ways. With only a small pool of marital possibilities, cousins often married cousins. As such, you might discover you descend from the same person in several different ways.

Simply tracing ancestors that far back in time can also prove confusing, as the branches of your family tree multiply dramatically with each generation. Though you have only four grandparents, you have 1,024 eighth-great-grandparents—that’s more than 500 possible surnames to research in the 1600s. Careful organization of your research is a must; grouping research not only by family but also by geography can help. (I have file folders, for example, labeled “Dickinson—North Carolina” and “Clough—Virginia.”)

As the colonies grew westward, their county boundaries shifted—sometimes dizzyingly so. The Carolinas, in particular, created a county crazy quilt over the years, meaning that your ancestor’s records might be found in multiple locales even if they stayed put. If your North Carolina kin settled in modern Orange County, for example, it helps to know that a county by that name didn’t even exist until 1752, when it was spun off from portions of Bladen, Granville and Johnston Counties.

Even colony- and state-level definitions changed. From 1641 to 1679, New Hampshire was technically part of Massachusetts. And the borders between some colonies weren’t decided for decades after settlement—sometimes, even until independence.

State and county pages on the USGenWeb site can help unscramble these switches. The Atlas of Historical County Boundaries at the Newberry Library lets you trace these changing county lines over the years, state by state, complete with animated maps beginning in the 1600s.

When your roots go back this far, you’re bound to uncover some tangles. You might not find ancestors who landed at Jamestown or who sailed aboard the Mayflower. But whatever you learn about these Colonial kin will broaden your understanding of American history.

Versions of this article appeared in the February 2006 and May/June 2023 issues of Family Tree Magazine.