Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Identifying your immigrant ancestor is an exciting genealogical find. It can help you make the leap to your ancestral homeland and push your research back several more generations. But merely finding out that an immigrant ancestor was from “Germany” (or even narrowed slightly to “Preussen,” the largest of the 19th-century German states) isn’t helpful information.

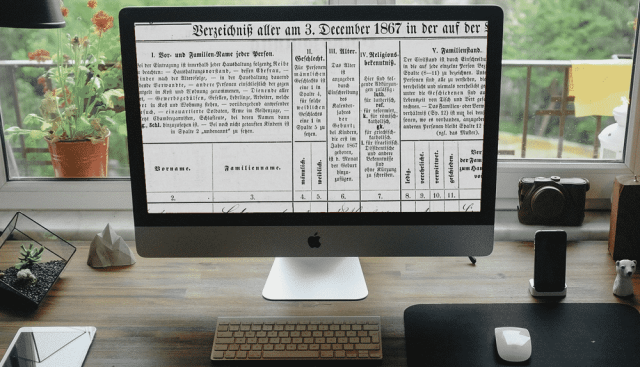

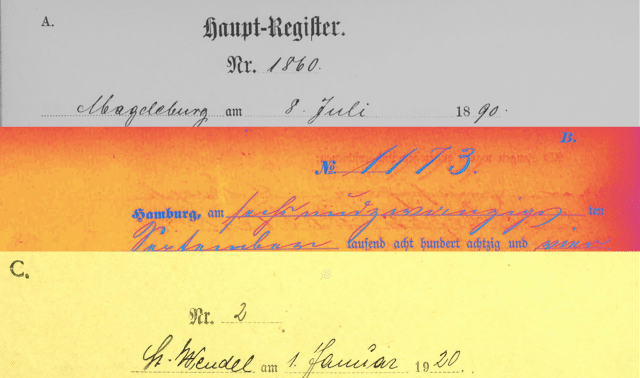

There’s no central repository of records in Germany, and during the period of heaviest emigration, there was no standard of what records were kept and preserved. The types of records you’ll find depend on the place. That means your German genealogy research will be in local records.

But before you can search those records, you’ll need to determine at least the German-speaking sovereignty from which your ancestor emigrated and preferably, his or her actual village of origin, or Heimat. Naturalizations, passenger lists and censuses, unfortunately, are usually unspecific about the immigrant’s birthplace.

More than likely, you’ll need to research some or all of the six record types outlined here to find the name of the town or village and take your genealogy journey to Germany.

1. Start with Home Sources

Any document, record or artifact in your home that contains genealogical information is a home source. The family Bible, scrapbooks, funeral cards, birth and wedding announcements, newspaper clippings, yearbooks and city directories are examples of home sources. Pay close attention to these for immigration clues.

Don’t dismiss items that may look like scrap paper or be difficult to understand, such as letters from relatives. If you find documents written in German, you can get a serviceable translation using a tool such as Google Translate, or hire a professional translator. (Find a directory on the Association for Professional Genealogists website.) Family Tree Magazine has a free downloadable guide to German script.

Some couples would receive a family Bible upon marriage, and these often had charts and blanks to record family information. People could fill in these blanks themselves or take them to a professional scrivener for completion. Blanks filled in by family members at the time of the event tend to be more accurate with the dates than those filled in by a scrivener at a later date.

Families may have decorative keepsake certificates, known as Fraktur (short for Frakturschriften, which means “broken writing” in German because each letter is inked without connecting to another letter), to mark a birth, baptism, confirmation or marriage. The most common type of these records is a baptismal certificate known as a Taufschein.

The production of Fraktur began during the 17th century and continued well into the 19th century. By the end of the 1700s, printers were selling templates that Fraktur artists, family members or pastors would decorate and infill with baptismal, confirmation or marriage information. As collectible as pieces of folk art, Fraktur have been collected by historical societies and published in art books such as Fraktur: Folk Art and Family by Corrine and Russell Earnest (Schiffer).

2. Search Online

The internet holds an array of possibilities for finding your immigrant’s village of origin, and the list starts with the two super-heavyweights of the online genealogical world:

Ancestry.com

The world’s largest subscription genealogy website, the site has records such as passenger lists, US censuses, naturalizations, port of Hamburg departure lists, vital records, obituaries and much more. Ancestry.com also has German-specific records including the Württemberg Emigration Lists that track thousands who applied to leave the German state of Württemberg, as well as passenger lists on which at least half the people aboard were German. Note that some of these collections come only with Ancestry.com’s international subscription package.

FamilySearch

FamilySearch is free to all researchers and is rapidly expanding its reach, which include images of the documents its affiliated, Salt Lake City-based FamilySearch Library has on microfilm. There, you’ll find German church records, though the percentage of these records that has been digitized and made searchable is still relatively small.

Another useful tool is the International Genealogical Index (IGI), a database with many records abstracted from German church registers. Search just the IGI for a surname, or run a name-search for all of FamilySearch’s indexed records. Check the matches to see which German villages have concentrations of that name.

Other websites

Of course, many, many other websites might tie your immigrant to a village. Type your ancestor’s name in a general search engine such as Google or Bing and see what comes up.

Many present-day German states also have emigrant databases you can search, especially if you’ve found an immigration record that suggests a particular German state as the origin. For example, the website Auswanderung aus Südwestdeutschland (Emigrants from Southwest Germany) has a database of 19th- and early 20th-century emigrants from the present-day German state of Baden-Württemberg and includes the former territories of Hohenzollern in addition to Baden and Württemberg. Find a list of such databases at German Roots.

3. Check published compilations.

Published works are secondary sources because they take primary or original information and essentially repackage it. Given the ubiquity of German immigrants’ descendants in America, many repositories—from public libraries to county historical and genealogical libraries—have good collections of books listing immigrants. You also might find books online at sites such as Google Books and FamilySearch Books. AbeBooks, eBay and WorldCat also are great websites to search for the types of published compilations described in this section.

Try to find family history books concentrating on a particular surname or descendants of your immigrant ancestor. Some of these histories are well-sourced and created with integrity, but others have very little source material. Use these histories as clues for your research and search for historical records to prove or disprove the information.

Histories of your ancestors’ US counties or towns are another possibility. Most of these were published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and their content is largely biographical sketches of area residents. These biographies often contain incorrect information because they usually relied on local residents’ memories, which weren’t verified with primary sources. But these histories can be a useful starting point and might list an accurate immigrant origin.

Try taking a “whole-family genealogy” approach when searching for published histories. A county history may contain the biography of a distant cousin who shares the same immigrant ancestor as you. This is especially true for descendants of families that immigrated in the 1700s, and the subject of the biographical sketch will be generations removed from immigration. County historical or genealogy societies may keep lists of published histories for the local area.

You can also find book compilations that tie together an immigrant with his Heimat using German primary source records that specify village origins, or by matching together German and American primary data. See the toolkit on the next page for a sampling of these, and look for each author’s other works. Former University of Pennsylvania professor Don Yoder, for example, has leveraged connections to German genealogists to compile data of emigrants (Auswanderungen) from German archives, newspaper advertisements for heirs, and notations in church books. The fruits of this labor include works focusing on Pennsylvania Germans.

Researchers Henry Z. Jones Jr. and Annette K. Burgert have compiled books that dovetail primary sources such as church, land and ship records from both sides of the ocean to identify village origins of thousands of 18th-century German-speaking immigrants. Jones’ works focus on the Palatinate. Burgert’s works include a master index to all the emigrants she’s documented.

Another genealogist, Werner Hacker, has meticulously abstracted thousands of references to emigration from archives in German states and matched them up with limited American data. His many works are indexed in Eighteenth Century Register of Emigrants from Southwest Germany to America and Other Countries (Closson Press).

4. Check Unpublished Compilations

One great resource that’s not online or even in a book is the Palatine Emigrant Index, which consists of thousands of index cards that reference records from both sides of the ocean in an attempt to show where emigrants came from and went to. The original cards are at the Institut für Pfälzische Geschichte und Volkskunde (Institute of Palatinate History and Folklore), previously known as the Heimatstelle Pfalz (Palatinate Home Office) in Kaiserslautern, Germany. Find a digitized copy through the Foundation of East European Family History Societies.

An even larger card file called Die Ahnenstammkartei des Deutschen Volkes (The Master File of the German People) contains about 2.7 million names from more than 11,000 pedigree files. The original card file is at the Deutsche Zentralstelle für Geneologie (German Center for Genealogy) in Leipzig, Germany; a microfilm copy of the card file and its indexes is at the Family History Library (FHL).

Examine the holdings of local and regional American libraries, especially in places where your ancestors lived, for unpublished resources related to the heritage of local German immigrants.

5. Read the Papers

Newspaper obituaries, especially those published in the first half of the 20th century, often give a person’s place of birth. You can search for your ancestors’ obituaries on a number of websites, including GenealogyBank (a subscription site that also has full digitized editions of papers), Legacy.com, Obituary Central, Obituary Daily Times, Newspapers.com (another subscription site with entire papers), USGenWeb Archives Obituaries Project, and USGenWeb Archives. Also check German-language newspapers in the person’s American hometown. You can search the Chronicling America directory of newspapers published in the United States by language; the directory listings name libraries that hold copies of each paper. GenealogyBank includes a number of German-language titles in its stable.

Take your newspaper research beyond obituaries, too: You may find the mention of a village in articles about your ancestors or their businesses, articles about family reunions, and genealogy columns. The good news is that many old newspaper collections have been digitized and put online, making them more accessible and easier to search than ever before.

Search newspapers published in the places and times your ancestor lived, but also check papers published in previous residences. Newspapers often shared articles with publications in other communities where former residents still might have been known.

6. Seek More Death Records

Each recording of a death in places such as official vital records, church records and cemeteries is likely to have different information, and you don’t want the source you failed to pursue to be the one that would’ve supplied a birthplace. Sometimes your ancestor’s village of origin will be listed right on his or her tombstone. You can find cemetery information and even images of tombstones on websites including BillionGraves, Find A Grave, Interment.net, Nationwide Gravesite Locator, Mortality Schedules and Virtual Cemetery. The cemetery itself may maintain a database of burials there. The caretaker’s office may have records with additional information, so call to ask.

Church burial records also may list the deceased’s birthplace. FamilySearch may have the church’s records on microfilm (search the online catalog by place and look for a church records heading) or if the church still exists, contact the office to ask about genealogy requests. Churches aren’t obligated to provide the information, so be patient and offer a nominal donation.

Once you’ve found the village name of your immigrant in one or more sources, you can begin tracing your family in German records. This process is covered in detail in The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide, which will help you locate the village in Germany, learn more about its history and language, and working with records from the area. Finding your immigrant ancestor’s village can be difficult, but when you do, you’ll unlock new records and new generations of family in the old country.

Tip: Thoroughly examine any record you come across for clues—even postmarks of letters sent from German relatives have helped genealogists find villages of origin.

Tip: Try taking a whole-family genealogy approach when searching for published histories. These books may contain the biography of a distant cousin who shares the same immigrant ancestor as you.

Toolkit

Websites

• Ancestry.com: German Records

• Bremen Passenger Lists

• Chronicling America US Newspaper Directory, 1690-Present

• FamilySearch International Genealogical Index

• GEDBAS German family trees site

• GenealogyBank: Ethnic Newspapers

• German Emigration Records

• German Genealogy Records and Databases

Books

• Pennsylvania German Church Records of Births, Baptisms, Marriages, Burials, Etc., 3 vols. by Don Yoder (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

• The Palatine Families of New York: A Study of the German Immigrants Who Arrived in Colonial New York in 1710 by Henry Z. Jones, Jr. (Picton Press)

• More Palatine Families: Some Immigrants to the Middle Colonies 1717–1776 and their European Origins, Plus New Discoveries on German Families Who Arrived in Colonial New York in 1710 by Henry Z. Jones Jr. (self-published)

• Even More Palatine Families: 18th Century Immigrants to the American Colonies and Their German, Swiss, and Austrian Origins, 3 vols., by Henry Z. Jones Jr. and Lewis Bunker Rohrbach (Picton Press)

• Westerwald to America: Some 18th Century German Immigrants by Annette Kunselman Burgert and Henry Z. Jones Jr. (Picton Press)

• Master Index to the Emigrants Documented in the Published Works of Annette K. Burgert, F.A.S.G., F.G.S.P. by Annette K. Burgert (AKB Publications)

• Eighteenth Century Register of Emigrants from Southwest Germany by Werner Hacker (Closson Press)

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.