The United States’ fastest-growing ethnic group, Hispanics, includes many who trace their origins to Mexico, and their interest in researching south-of-the-border family history is muy caliente. Fortunately for those with roots in Mexico, this enthusiasm has benefited from a wealth of new tools for online genealogy. Combined with the extensive availability of microfilmed Mexican records at local FamilySearch Centers, it’s now easier to get started on your research on this side of the border than in Mexico itself.

Most notable among the additions to clickable Mexican records are the digitization and indexing efforts at FamilySearch.org, which is also home to the FamilySearch catalog of collections at the Family History Library (FHL). The FamilySearch.org online collection now includes 19 Mexico-specific indexed record sets and another 46 browsable image collections—tens of millions of records in all. (Note, by the way, that most of the Mexican records online at subscription genealogy sites duplicate those available for free at FamilySearch.org.)

The records at FamilySearch.org include the 1930 Mexican census and a significant portion of the two most important sources for Mexican research—Catholic Church parish records and civil registration records, organized by state. Although more than two-thirds of these parish and civil registration records groups have yet to be indexed, browsing them online can be much faster than borrowing one or two microfilm reels at a time. One of the challenges of Mexican research, after all, is the sheer volume of records: one reel of microfilm might hold only six months of records. Use our guide to start searching for kin in this bounty of records.

Understanding Mexican Naming Patterns

Before you can start finding your Mexican ancestors in this wealth of records, you have to know whom you’re looking for and where to look. Mexican naming patterns can provide plenty of clues, but they also can confuse those unfamiliar with Spanish traditions.

Start with the language itself, which is dotted with accent marks unfamiliar to English-only speakers. Unlike in some languages, accent marks don’t affect alphabetization in Spanish, but you will encounter three extra letters in the alphabet: ñ (counted as a different letter from a tilde-less n, and pronounced like “ny”) plus the combinations ch and ll, which are also considered as if they are single characters. All three are alphabetized where you would expect—after n, c and l, respectively—but keep in mind that a name starting with Cr-, for example, would come before one beginning Ch-.

Given names

Given names in Mexican families also can feel like they have some extras. In addition to the standard first name, children often receive a baptismal name (nombre de pila), typically that of the saint whose feast falls closest to the baptism day. The child might never be called by this extra name, but it could confuse you when looking in church records. You also may have to disregard a superfluous José or María the parish priest often added to a boy’s or girl’s name, respectively.

Surnames

Historically, surnames followed several Spanish patterns, which might hold important genealogical clues. Some surnames came from occupations, descriptions or, potentially helpful, places (de Córdova, del Río). One common derivation added a suffix (-az, -ez, -iz, -oz or -uz) to the parent’s name, as in Martínez, meaning the son of Martín.

This system resulted in the proliferation of certain surnames, which can make it challenging to differentiate your ancestors. In 2005, for example, the 10 most common surnames in Mexico were Martínez, García, Hernandez, González, López, Rodríguez, Pérez, Sánchez, Ramírez and Flores. Collectively, these 10 surnames add up to 31 million people in present-day Mexico, or roughly one in every four Mexicans.

Surnames, too, can pile up, as they did back in Spain, combining surnames from the father’s and mother’s families using a preposition (de, del, de la), a dash or simply y for “and.” You’ll want to comb records for all possible variations—checking, for example, under De la Cruz as well as Cruz, de la.

Maiden names

In a boon to genealogists, Mexican women historically kept their maiden names when they married, adding the husband’s surname with a preposition. So when Consuela Herrera wed Diego Martínez, she would became Consuela Herrera de Martínez. A widow would add viuda or the abbreviation vda, as in viuda de Martínez. Records of US border crossings commonly used the woman’s maiden name, too, but check all possible variations.

Pinpointing ancestral whereabouts

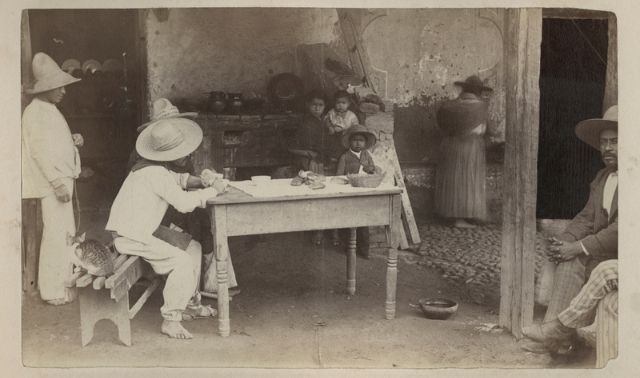

Figuring out the where of your ancestors’ history, as with most ethnicities, is as essential as knowing whom to look for. Arturo Cuéllar-Gonzalez, a research specialist for Latin America at the FHL, says, “Finding where your ancestors were from… is as much an art as science. The types of food your ancestors ate, family recipes, songs and stories handed down for generations are hints that may give you some guidance. The type of climate or terrain or major storms and destruction you’ve heard shared through family stories can provide other clues. Old pictures in unique settings or with writing on them, or the types of dress shown in the photos might help.”

If your ancestors arrived fairly recently or you can identify relatives who remained in Mexico, the 1930 census at FamilySearch.org might help place them on the map. “Prior to the Mexican Revolution, 95 percent of the land in Mexico was owned by 5 percent of the people. In preparation to form a policy of land distribution, the Mexican government created a census so land ownership could be recorded and conveyed,” Cuéllar-Gonzalez says. “This was one of the first mandatory accountings of everyone and included name, age, gender, birthplace, address, marital status, nationality, religion, occupation, real estate holdings, literacy, any physical or mental defects and any Indian language spoken.”

Keep in mind, however, that the 1930 census records are missing for some places, including Mexico City (the Distrito Federal). And many Mexican names are similar, meaning you’ll need contextual clues to identify your family amid the other Gonzálezes and Lópezes.

If your ancestors arrived in the United States across the Mexican border after about 1895, their immigration records—which list place of birth in Mexico—may be in the collections of the US National Archives and Records Administration. These border-crossing records are also available on the subscription site Ancestry.com and on FamilySearch.org.

Finding an ancestor in Mexican church records, the key source before 1860, requires knowing an ancestor’s parish and its location. You may find multiple parishes in larger cities, and the town linked to a parish may not match that for civil registration records. Boundaries frequently shifted in Mexico, further complicating matters. Read about territorial boundaries in Mexico here and changes to Catholic parishes and dioceses here.

Microfilmed batch numbers

Once you’ve located an ancestral family in Mexico, one helpful tool to find others in the same area is the batch number logged when FamilySearch originally microfilmed the records. FamilySearch has de-emphasized batch numbers as its International Genealogical Index (IGI) has become a “legacy” database, no longer actively maintained. But you can still search the IGI, an index to vital records that includes extensive coverage of Mexico.

You also can find batch numbers when you search the newer FamilySearch.org online databases of Mexican records. When you’ve found one family member’s record, clicking on the batch number at the bottom of the entry (such as “I06840-9”) brings up a list of all the records microfilmed in that same batch—likely including more of your relatives. You also can choose to restrict your search by batch number (under the Restrict Records By section at the bottom of the main search page for each collection).

This trick works in reverse, too, if you know your ancestral town. You can find the batch numbers associated with many Mexican locations using the index.

Civil Records

Unless your family left Mexico long ago, the first important genealogical resources you’re likely to use are civil registration records. The Civil Registration Office (Registro Civil) has kept these vital records of births, marriages and deaths since its establishment on July 28, 1859, by President Benito Juárez as part of his governmental reforms. Compliance was slow, so it’s important to check parish records as well (see the next section), especially for the early years of civil registration, prior to the restoration of the Mexican republic in 1867.

The FHL has microfilmed civil registration records from thousands of local offices (municipios) across Mexico, each of which might cover several towns. But you will encounter some gaps, notably for the states of Sinaloa and Tabasco, and not all collections extend past the early 20th century. Keep in mind some local quirks, too. For example, some Quintana Roo records were microfilmed with those for Yucatán, and the states of Guerrero and Oaxaca archived their records at the district, rather than the municipio level. Civil registration records in the Distrito Federal are kept in “delegations.”

You can search records for locales whose civil registration records have been digitized and indexed on the FamilySearch.org website, including for Aguascaliente (1859-1961), Chihuahua (1861-1997), Coahuila (1861-1998), Distrito Federal (includes additional pre-1859 records, 1832-2005), Guerrero (1860-1996), San Luis Potosí (1859-2000) and Tlaxcala (1867-1950). You must browse others as online images or view them on microfilm. This isn’t necessarily as onerous as you might guess from, say, the count of 1,413,921 civil registration records online for Guanajuato (1862-1930). Clicking on the link for online images brings up a list of cities and municipalities, which in turn has a list of links by record type and year. You may have to jump around from page image to page image to narrow your browsing to the most likely pages for your family’s data, but it’s not impossible.

It’s worth this exercise in patience because civil registration records are packed with genealogical information. Birth records (nacimientos) usually contain the name of the child, gender, date and place of birth and parents’ names. Marriage records (matrimonios) typically include the names of the bride and groom; date and place of the marriage; the groom’s and bride’s ages, occupations, civil status, origins, nationalities, residences and parents’ names; and witnesses’ names, ages, civil status, occupation, residence and relationship to couple. More recent marriage records are more likely to contain most or all of this information. Death records (defunciones) may give the name, age and gender of the deceased; place of birth; occupation and residence; date, time, place and cause of death; burial information; and informant’s name and relationship to the deceased.

Church Records

To push your research back before the 1859 launch of civil registration, you’ll need to turn to parish records of the Roman Catholic Church, which was Mexico’s only recognized church until that same year. The first Mexican diocese, Tlaxcala, was established in 1527, and several others date from the 16th century. The last to be established were in Puebla in 1903 and Yucatán in 1906. Parish registers (registros parroquiales) recorded baptisms (bautismos), marriages (matrimonios), deaths (defunciones) and burials (entierros).

FamilySearch.org has combined some records for baptisms (1560-1950), marriages (1570-1950) and deaths (1680-1940) into three searchable collections. The baptisms database is by far the largest of these, with more than 43 million records. You also can search individual collections of digitized parish records from Coahuila (1627-1978), the Distrito Federal (1514-1970), Durango (1604-1985), Hidalgo (1546-1971), Puebla (1545-1977), Querétaro (1590-1970), Sonora (1657-1994) and Zacatecas (1605-1980). Records for other locations are also online, but must be browsed.

Baptismal records

Records of baptisms, which generally occurred within a few days of a child’s birth, usually include the infant’s name and status of legitimacy; place and date of baptism (the actual birth date also may be listed); and parents’, godparents’ and sometimes grandparents’ names. Some records also give the family’s place of residence or the birthplace of the parents, as well as racial information. Notes may mention if a child died in infancy or even that a child grew up and got married.

Marriage records

Marriage registers list the names of the bride and groom and the date and place of marriage (usually in the home parish of the bride); names of witnesses; place of residence for the bride and groom; and names of their parents, often noting whether the parents were living at the time. Marriage records also may include the birthplaces and ages of the bride and groom. (Don’t be surprised at the difference in these ages: Typically girls married between the ages of 14 and 20, while men married in their 20s.) When one or both of the couple was a minor, the register may note parental or other permission for the marriage. If this was a second marriage for either party, the register usually omits the parents’ information for the widowed individual, but may give the name of the deceased spouse and how long the spouse had been deceased. (You can then track down the register for the first marriage to find the missing parental data.)

Death records

Records of deaths are typically combined with those of burials, with a note from the parish priest giving the date stating something like “I the priest [name] gave ecclesiastical burial to the corpse of [deceased’s name].” Women are usually recorded by their maiden name, with a spouse’s name listed if married. Other information in parish death and burial records may include the deceased person’s age, place of residence, marital status, cause of death and other survivors of the deceased. The priest also may note whether the person left a will. If the deceased was a minor, his or her date and place of birth and parents’ names may be included, especially in later death records.

Catholic church records

Catholic churches also recorded additional information in conjunction with key events in a parishioner’s life, although these records have not been as widely microfilmed. Larger parishes, for example, would keep a separate book to record confirmations (confirmaciones), while these were intermingled with baptism records in smaller churches. Confirmation records usually contain only the name of the confirmant, his or her parents’ names and the names of the godparents. These records are most useful to confirm family ties found in other records. In small or remote parishes, where the bishop or his representative might visit only every few years, several family members of different ages might be confirmed together, giving you a resource to identify siblings.

You may have to write to a parish archive for marriage information records (información matrimonial), also known as pre-marriage investigations, but these can be valuable if other records have gone missing. Before getting married in the Catholic Church, couples had to submit to a process to prove that they were in good standing in the church and had no impediments to marriage. The resulting documents included the couple’s names, ages, marital status and place of residence; their parents’ names; sometimes their birthplace and grandparents’ names; and names of witnesses and their connection to the couple. When one of the couple (typically the groom) grew up in a different parish, the file would include proof of his good standing in the home parish, possibly including baptismal records.

If the investigation turned up any red flags, documentation would show, for example, that the spouse from a previous marriage was deceased. Couples related by blood (consanguinity) or through marriage (affinity) would need dispensations, which might include charts showing their relationship.

Other church records you might seek out include wills and testaments, and ecclesiastical censuses. For ancestors between 1522 and 1820, you might even find records of the Mexican Inquisition, the infamous Spanish Inquisition’s extension into the New World. Trial proceedings of the Inquisition can hold detailed genealogical information the accused provided to prove pure Hispanic-Catholic origins.

Other Records

If you’ve struck out finding Mexican ancestors in civil registrations and parish records, there are other resources you can try. But such otherwise familiar record sources such as cemetery records, censuses and probate files are less readily available for Mexican research than for US ancestors.

Cemetery records

Few cemetery records have been transcribed or microfilmed. You’ll have to look for them at municipio archives, local parishes and historical societies or libraries. (The exception is the Distrito Federal, where the FHL has microfilmed some cemetery records.) BillionGraves has nearly 50,000 Mexican cemetery entries and is also searchable through FamilySearch.org.

Censuses

That 1930 enumeration is the only comprehensive census that covers all of Mexico, and you can search it online at FamilySearch.org. Various censuses called padrones were taken during Mexico’s colonial period, beginning in 1752, and in the early years of independence, typically to identify men eligible for military service. The FHL has microfilmed these, along with a 1689 special census of Spaniards living in Mexico City in 1689. (Records of actual military service, by the way, aren’t readily accessible; colonial military records are in Spanish archives.)

Probate and notarial records

You’ll have to seek out probate records in notarial files, parish records and municipio court records. Few have been microfilmed with the exception of vínculos (entailed estates) from 1700 to 1800. Those notarial files, common in Hispanic countries, include records such as wills, dowries, guardianships and mortgages kept by notaries (notarios). Again, few have been microfilmed and you must look for them in state and local archives.

Divorce records

Divorce records, another familiar resource for relatives north of the border, simply don’t exist in this Catholic country until 1917, when the new Mexican constitution legalized divorce. Contact the clerk of the town or municipio courts where the divorce took place.

Land records

The FHL has microfilmed some land records; most of the originals are at the national archives in Mexico City. The Texas General Land Office’s Spanish Collection holds 4,200 land titles from 1720 to 1836 for what is now Texas. And the New Mexico State Records Center and Archives has 1693 to 1821 Spanish land records and 1821 to 1845 Mexican records for what’s now the Land of Enchantment.

These “Plan B” records require some effort to access, but chances are you’ll find the family history answers you seek in the Mexican records riches readily available on microfilm and, increasingly, online.

Tip: Mexico City, the capital of Mexico, is officially known as the Federal District, or in Spanish the Distrito Federal. It’s also referred to as México, D.F.

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine .