Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

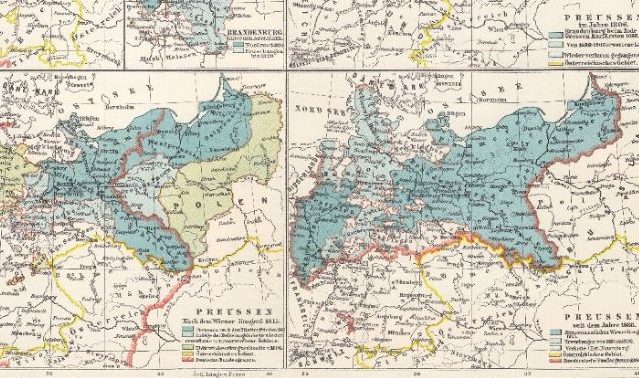

Many things are said to be a “state of mind.” For genealogists seeking 19th- and early 20th-century ancestry in what was then the largest German Empire state of Prussia, “Prussian” is a kind of a state of mind. The term’s meaning differed greatly during the half-millennium in which the Hohenzollern family wielded power in Central Europe, many of its members crowned “Kings of Prussia.”

For researchers with German ancestry, the word “Prussia” can be a stumper—and the fact that there’s no such political unit with that name in present-day Europe is just the conundrum’s starting point. German immigrants may have been grouped together as the overly broad term “Prussians.” The misleading label may believe their actual identities: Pomeranians, Rhinelanders, Hanoverians and more.

However, an “attitude adjustment” will help you solve your Prussia problems. This guide goes through the best Prussian genealogy records that may help you pinpoint your ancestors’ origins. I’ll walk you through three steps to tracing your Prussian ancestors.

Step 1: Find a Prussian Town of Origin Using US Records

In many cases, the first reference to Prussian ancestry that you see will be from an American record. You might even be happy to see that detail rather than the even more generic “Germany”—until you look at the map and realize how big Prussia had become in the 19th century.

Two related pieces of information can come to your rescue. Some US records may yield the gold standard of immigrant genealogy research: an exact village of origin. Or, at least, a record might identify a Provinz (province; plural is Provinzen) to narrow down the search to a particular area of Prussia.

Here are some of the US records most likely to reveal your Prussian ancestor’s town of origin.

Church and Vital Records

While every record of an immigrant, spouse and children has some potential for a specific village name, church records are far and away the most likely to include such information. You can find large collections of ethnic German American congregational registers on the free FamilySearch as well as major subscription sites Ancestry.com and MyHeritage. (US civil vital records, too, might have specific place names, but this is less likely.)

A team led by German genealogy scholar Roger P. Minert continues to compile the valuable book series German Immigrants in American Church Records (Family Roots Publishing). Minert has published more than 20 volumes to date, each with an abstract showing origins written in the more commonly used church registers (baptisms, marriages and burials) but also harder-to-find record groups such as membership lists. In addition to the individual volumes, which you can find in libraries that have substantial German genealogy collections, Minert has created a set of consolidated indexes to the first 14 volumes, which you can find in libraries with large German collections.

In addition to church records, tombstones (often more detailed in earlier eras than they are today) will sometimes have villages of origin carved on them. Find a Grave has become the leading site showing memorial information, but there are still many offline sources such as marker transcripts in county historical and genealogical libraries.

Federal Censuses

Fortunately, many US censuses inquired about the respondent’s place of birth, making them a possible source for your ancestor’s Prussian origins. Questions varied by census year—and didn’t guarantee that the enumerator would follow the proper instructions—but may still provide some insight:

- 1850: Enumerators were to use “the name of the government or country if without the United States.” Many used “Germany,” even though that was not yet technically a country. But you might still see references to Prussia or smaller contemporary German states such as Hesse.

- 1860 through 1880: Instructions said that “Germany” was too general of a response, and requested that the enumerator gather what state within the region if possible. (From the 1860 instructions: “To insert simply Germany would not be deemed a sufficiently specific localization…the particular German State should be given—as Baden, Bavaria, Hanover.”)

- 1900: The instructions reverted back to less-specific country/region, encouraging Germany over Prussia or Saxony.

- 1910: Germany wasn’t mentioned, but the instructions seemed to encourage more specificity. For example, the enumerator was to distinguish between the different parts of partitioned Poland (i.e., “German Poland” instead of just “Poland”) or the two main constituent countries of Austria-Hungary.

- 1920 through 1940: Enumerators were asked to distinguish between (in 1920) the provinces of dissolved empires like Germany. Similarly, in 1930 and 1940, enumerators were to ask what country the person’s birthplace was in as of 1930 and January 1, 1937 (respectively), taking into account recent border changes.

Immigration and Naturalization Records

US passenger arrival lists often give birthplace (or place of last residence) data. But for the many Prussians who left via the port of Hamburg, embarkation lists show even more detailed information. These embarkation lists (as well as handwritten indexes for them that might be needed as a workaround for bad handwriting) are available on Ancestry.com.

Naturalization documents are especially important if your ancestor became a citizen (which you can determine by examining federal censuses). For most, naturalization was a two-step process that required a declaration of intent followed by a petition for naturalization. Both contain valuable information about origins; make sure you look for both document types. (Note: Naturalization documents contain uniform information after the process was federalized in 1907, but details will vary in earlier records.)

You can also find geographic-specific databases of emigrants relating to Prussian areas. For example, the Schleswig-Holstein Rootdigger group has more than 100,000 emigrants documented, while the website Ahnenforschung im Internet—Raum Rheine has hundreds of emigrant names from the Rhineland.

Societies

Once you have some more direction about your ancestor’s province, consult resources created by individual societies and genealogy groups about “Prussians” who came from a particular region. To give just two examples:

- The Ostfriesen Genealogical Society of America has an emigrant database listing some 30,000 people from Ostfriesland (East Frisia/Friesland), part of the Kingdom of Hanover that was annexed by Prussia in 1866.

- Pommerscher Verein groups were formed by descendants of emigrants from the Prussian province of Pomerania. One such group, Pommerscher Verein Central Wisconsin, has a library of difficult-to-find church records.

Step 2: Map Your Ancestral Town

Even once you have a town name, you might not be able to simply type it into Google and locate it on a modern map of Germany. Perhaps the name is misspelled in a record or has multiple names. Or maybe there are too many villages with the same name to pin down your ancestor’s—like how there’s a “Springfield” in nearly every US state.

When you face one of these problems, your first stop should be the Meyers Gazetteer, the leading geographical dictionary of German lands published in the Second Empire period and available online. The online version of “MeyersGaz” includes the original gazetteer’s detailed information on each town, then supplements it with interactive modern-day and historical map overlays.

Specifically for Prussian areas that are now in Poland, Kartenmeister gives loads of information about the villages east of the Oder and Niesse rivers (the current boundary between Germany and Poland). The profile for each town name includes both German- and Polish-language place names, as well as what districts and parishes the villages belonged to.

Another valuable tool can be the “Prussia, Municipality Gazetteer, 1905” (Gemeindelexikon für Königreich Preussen) on Ancestry.com. This gazetteer can be helpful in determining which Catholic and Protestant parishes a village belonged to—information not found in the Meyers Gazetteer. (Kevan Hansen’s Map Guide to German Parish Registers series, found in many libraries that have German collections, can also give this information.)

You also won’t want to miss the Germany-based supersite CompGen, which hosts research-aid primers for all of the former Prussian provinces, a historic gazetteer (GOV) and links to many regional groups.

Step 3: Find Prussian Genealogy Records

Once you’ve found your ancestral town of origin and located it on a map, you can consult a few different resources for Prussian records.

The FamilySearch Library has large volumes of microfilm containing births, marriages and deaths from historical Prussia. Many of these have been digitized and indexed; look at FamilySearch’s list of collections to see what’s available for “Prussia” or the modern German/Polish state your ancestor’s town of origin is in.

Some of these collections are also on Ancestry.com and MyHeritage, since the two companies helped fund some of FamilySearch’s digitization projects.

Church archives themselves are digitizing records from their congregations. Archion.de and Matricula have growing browsable databases of Protestant and Catholic records, respectively.

Prussian civil registration dates to 1874 in most places, and (for the most part) are kept in the civil registry office (Standesamt) where the event occurred. Some local groups are transcribing them, but you’ll need to write to the office to get records from most places.

Standesamt I in Berlin holds duplicate copies of civil registries in eastern Prussian territories now in Poland or Russia. Ancestry.com has a collection of these records: “Eastern Prussian Provinces, Germany [Poland], Selected Civil Vitals, 1874–1945.”

Other record groups haven’t survived the region’s tumultuous 20th century. Most military records, for example, were unfortunately destroyed in WWII bombing (though documents from independent Hanover have survived). Likewise, early German censuses were thrown away, though some remain in local government archives.

Prussian genealogy research isn’t always easy. But with the right attitude, dedication and tools, you can find your ancestors who lived within the limits of the former kingdom.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2021 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: January 2024