When you go to vote this Election Day, whether you lean to donkeys or elephants, you’ll assume certain things: The ballot will be prepared by election officials, you’ll select candidates to vote for by a mark or punch or pulled lever, and your ballot will be secret. But these practices — not to mention voting technology — would surprise most of our ancestors. The first election fitting those three criteria was only 150 years ago, in Australia. And this “Australian ballot” didn’t make its way into a US election until 30 years after that.

The world’s first votes were cast long before, of course, as early as 508 BC in ancient Athens. But Athenian “democracy” — from the Greek for “the people rule” — resembled New England town meetings more than modern elections. Officials were chosen by lottery, and voting was negative: Politicians’ names were inscribed on pieces of broken pots — ostrakas, the root of our word ostracize — and if any received more than 6,000 votes, the “winner” was exiled for 10 years.

Positive voting wouldn’t catch on until 13th-century Venice, which elected a 40 member Great Council. But the practice of crossing out unwanted candidates’ names persisted into the 20th century, especially in Southern states.

Back when, citizens cast their votes with colored balls. The word ballot derives from the Italian ballot a for “ball,” and blackball comes from the Masonic practice of casting a black ball as a vote against a proposed member.

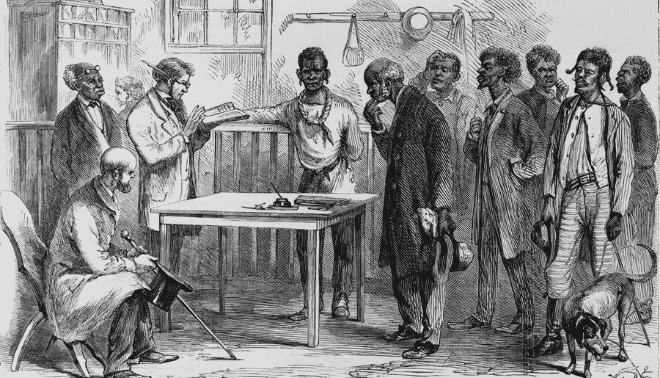

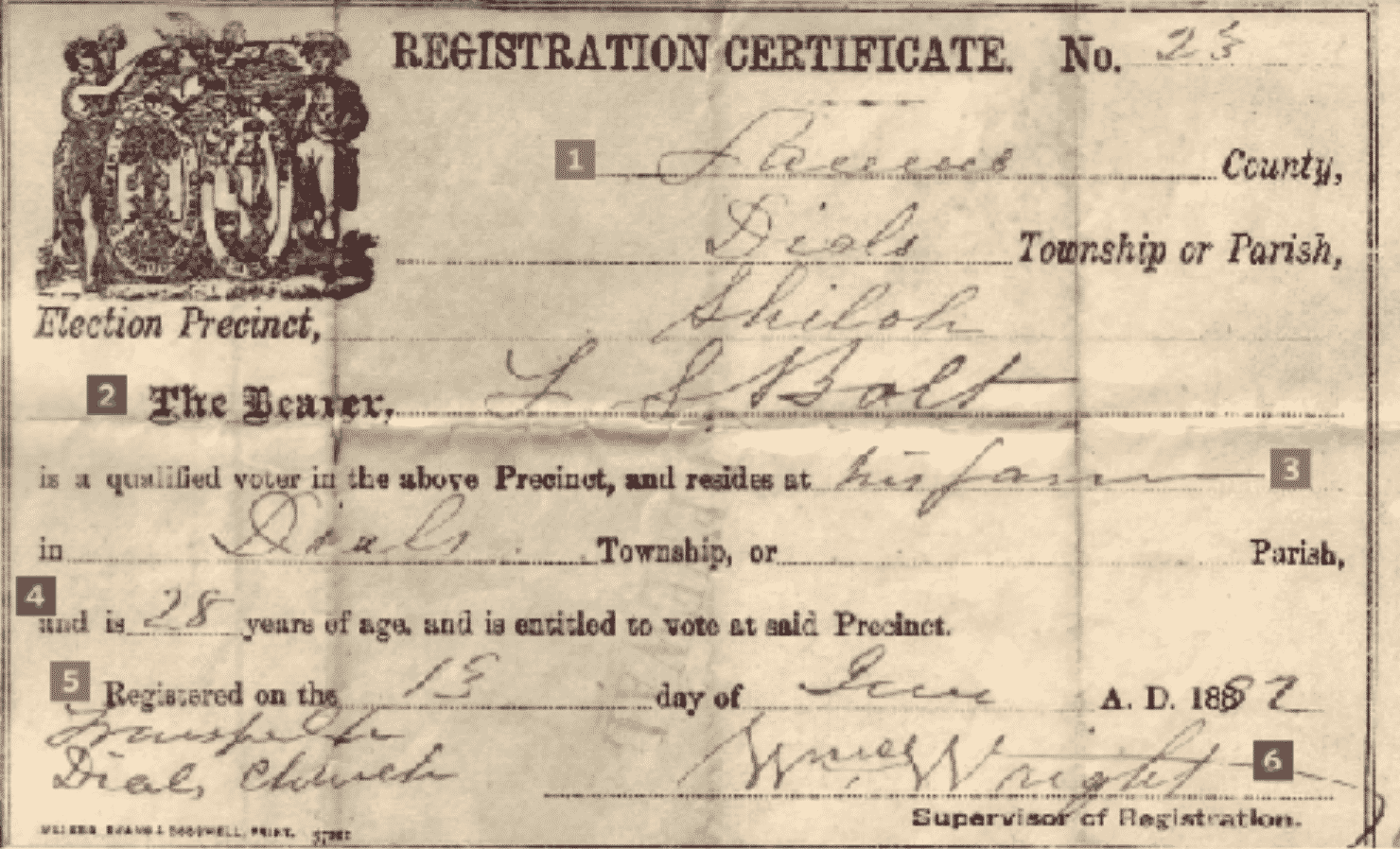

One alternative was voice voting. Voters would first take an oath — much of early America lacked voter registration, so such a vow and the fear of being recognized were the only prescription against voting “early and often” — and then announce their votes. Election clerks would record these voice votes, a system that persisted in some locales into the 1860s.

The ancient Romans had introduced paper ballots in 139 BC. In the United States, paper ballots were first used in 1629, to select a pastor for the church in Salem, Mass.

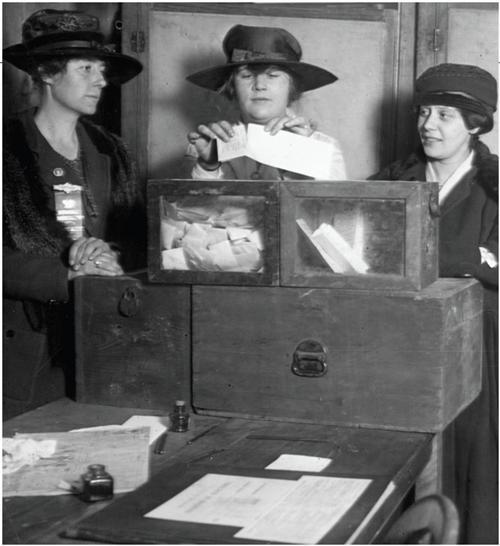

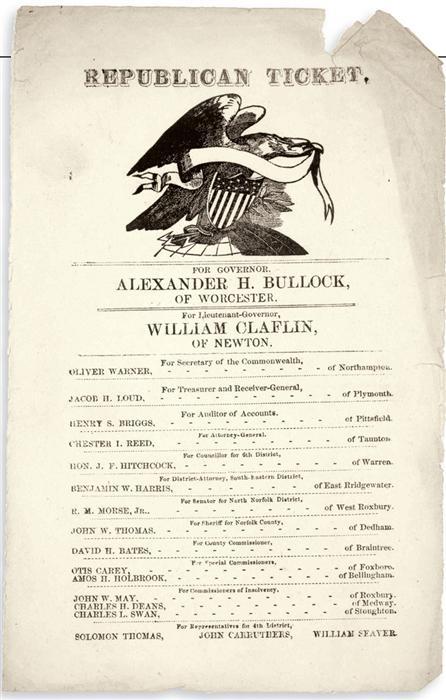

The first paper ballots were simply scraps of paper, supplied by voters themselves. As American political parties grew, however, partisans began printing ballots to make supporting their candidates easier. Because these ballots resembled train tickets, voting for the whole slate came to be known as a “straight ticket.” You could depart from the party line by crossing out a name and writing in the opponent — although tightly printed, barely legible partisan ballots made this almost impossible by the 1880s. In urban areas, ballots were printed on colored paper, so party poll watchers could easily tell how people voted (in a transparent ballot box, meant to avoid stuffing).

William Robinson Boothby (1829 1903) had a better idea. An Australian electoral commissioner and sheriff, Boothby pioneered the reform of officially preprinted ballots that voters cast in secret. As tested in 1856 in Victoria and Tasmania, the Australian ballot originally required voters to strike through the names of unwanted candidates. But in 1858, ballots instructed South Australia voters to make “a cross within the square opposite the name [of] the candidate for whom he intends to vote.” The modern ballot was born — and cast.

Opening the Polls

Boothby’s ballot caught on slowly in the United States, but the disputed presidential election of 1876 gave impetus to reform. New York and Massachusetts experimented with the Australian ballot in 1888. In 1892, Grover Cleveland became the first president elected in part with Australian ballots. The old party-printed ballots persisted in pockets of America, however: As late as 1940, Delaware and South Carolina still used partisan ballots.

Newfangled technology, thought to be more fraud-proof, began to replace paper ballots even as the Australian system spread. (By the 2004 presidential election, only 1 percent of US voters still used paper ballots.) First came the lever voting machine, whose clicking and whooshing remains the sound of democracy for many Americans who came of age in the 20th century. Invented by Jacob H. Myers, the Myers Automated Booth employed more moving parts than almost any other machine of its day. It was designed to “protect mechanically the voter from rascal-dom, and make the process of casting the ballot perfectly plain, simple and secret.”

First used in Lockport, NY, in 1892, lever voting machines were the standard in every major US city by 1930.

Lever machines went out of production in 1982, however, and by 2004 represented only 14 percent of American voting. Several technologies competed to supplant them, beginning with the “mark-sense scanning” originally used for standardized testing. In 1962, Kern City, Calif., became the first to use optical mark-sense ballots; the system to scan them weighed 15,000 pounds. By 2004, optical scan ballots accounted for 35 percent of US votes, more than any other system.

The punched-card machine, inspired by the Jacquard loom, was patented by Herman Hollerith in 1889 — the same year Myers patented his lever machine — and used in the 1890 census. But punched cards weren’t applied to voting until 1964, when political scientist Joseph P. Harris and fellow Berkeley professor William Rouvenol, a mechanical engineer, tested them at the Oregon State Fair and in two Georgia counties’ primary elections. The duo formed the Harris Votomatic company and obtained a patent in 1965. A descendant of their Voto-matic was involved in the 2000 Florida “hanging chad” controversy; in response, punched-card votes dropped from 31 percent to 13 percent of US ballots by 2004.

The latest wrinkle in voting technology, with nearly 30 percent of 2004 ballots, is the direct recording machine — an electronic (now computerized) twist on the old lever machine. The first direct-recording machine, the Video Voter, was used in Illinois elections in 1975.

Our ancestors would be amazed to see us voting by computer, with official ballots cast affirmatively and in secret. But not every change represents progress, of course: You never heard of the Athenians having problems with “hanging ostrakas.”

Party Time: Defunct Political Parties

Republicans and Democrats haven’t always dominated US politics. Your ancestors might’ve supported these defunct parties:

Federalist Party (about 1789 to 1820)

Nullifier Party (1830 to 1839)

Whig Party (1833 to 1856)

American Party, aka “Know Nothings” (about 1845 to 1860)

Free Soil Party (1848 to 1855)

Readjuster Party (1870 to 1885)

Liberal Republican Party (1872)

Greenback Party (1874 to 1884)

Vegetarian Party (1947 to 1964)

Websites, Books and Resources

These websites, books and museums are just the ticket for learning more about voting history:

Books*

The History and Politics of Voting Technology by Roy G. Saltman (Palgrave Macmillan)

Voting Technology: The Not-So-Simple Act of Casting a Ballot by Paul S. Herrnson, Richard G. Niemi, Michael J. Hanmer and Benjamin B. Bederson (Brookings Institution Press)

Websites

A Brief Illustrated History of Voting

Political Culture and Imagery of American Woman Suffrage

Women’s Rights National Historical Park 136 Fall St., Seneca Falls, NY 13148, (315) 568-0024

From the November 2008 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

*FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to Amazon and affiliated websites.