Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

If you’re a mother or an expectant mother, you may identify with your female forebears who’ve experienced the miracle of birth. But your modern childbirth experience likely bears little resemblance to your ancestors’.

“Women have been giving birth for thousands of years, but the way in which we do it—alone in a field, at home with female friends, in a hospital with male doctors, with or without pain relief—is a reflection of the culture of the time and place where it happens,” says Tina Cassidy, author of Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born (Grove Press). Even in modern America, how and where a woman brings her children into the world depend on factors such as her class, race, marital status and the social norms of her community.

Though a birth certificate or other vital record can tell you the basic facts—who was born to whom, when and (maybe) where—understanding how your female ancestors gave birth can reveal how they lived and create a profound connection with them. You may discover that the same midwife delivered children for generations of your Colonial ancestors’ family, that your great-great-grandmother died in childbirth, or that Grandma Betty and her husband spent half a year’s salary so she could give birth in a hospital with the latest pain-relief drug.

These birth history highlights will tell you how American women have labored and delivered from the 18th to the 20th century. Then use our research tips to deliver details about your own ancestors’ birth experiences.

The Social History of Birth

If your ancestors gave birth in America before the 1800s, they almost certainly did so at home under the care of a midwife and with support from female family and friends. This it-takes-a-village practice is often called “social birth.” When a woman went into labor, her husband fetched the midwife, a trusted local woman who had witnessed many births or who had learned her trade from another midwife. The husband also assembled several female friends and family members to support the laboring mother.

While the midwife was needed for her skills, the other women offered emotional support and helped run the home—tending to the housekeeping, cooking, caring for older children—during the mother’s recuperation, often called “lying in.” During this era, a woman typically gave birth in a room of her home, sometimes called a “borning room.”

If your ancestors lived in a remote community, a mother-to-be might not have had access to a trained midwife. Instead, a relative or neighbor who had been through childbirth herself would attend the birth. Slaves attended other slaves’ births in their own quarters, whether that was a room in the owner’s house, a barn loft or a stable.

To aid women in birth, midwives had all manner of tricks—some were folk traditions, others were medicinal herbs or tonics. Most early American midwives were immigrants and often used talismans, amulets, poems, songs or dance that reflected the ethnic and spiritual beliefs of their homelands. If your ancestor gave birth in the Appalachian region, for example, the midwife might’ve put a knife under the mattress to “cut the pain” of labor. Though many practices were simply superstition and did little to alleviate pain, Colonial women did receive some real relief. For instance, many midwives used opium or belladonna, a plant based-anesthetic also known as “deadly nightshade,” to quell pain.

Following lying-in, a woman would often host a feast to thank the women who helped her. Its name, “groaning party,” refers to the groaning involved in giving birth and that the feast should leave the women full to bursting. A midwife would receive a small cash sum, or food or goods in trade. For example, if your ancestor’s husband was a cabinetmaker, he might’ve built a hutch or pantry to “pay” the midwife.

In the early 18th century, as scientific understanding of the world grew and Colonial men began getting medical educations abroad (there were no medical schools in America yet), middle-class urban women began using doctors to deliver their babies. Though many women allowed men to deliver their babies at home, they still called on female friends and family for emotional and spiritual support.

Middle- and upper-class women embraced doctors and modern medicine, but religious beliefs persisted. Your early 19th-century ancestors expected to suffer in childbirth, as they believed God intended they should. Then Queen Victoria, head of the Church of England, inhaled chloroform while delivering Prince Leopold in 1853. Suddenly, using pain relief in childbirth became culturally acceptable. But unless your ancestor could afford to hire a drug-peddling physician, she would have had to go the natural route.

The first maternity hospitals in America, such as the Lying-In Hospital of the City of New York, were for the poor and destitute—prostitutes and single mothers. Though you might think these women were lucky to get the first shot at giving birth in a hospital, it wasn’t necessarily good: In the new hospitals, inexperienced doctors practiced in far-from-sanitary conditions. Many women contracted deadly infections such as childbed fever (also called puerperal sepsis) after doctors performed exams without washing their hands. A significant percentage of new mothers and their babies died from childbed fever until hand-washing became widely practiced, beginning around the late 1880s.

Despite the risks, your pregnant ancestors continued to check into hospitals. Although fewer than 5 percent of women had hospital deliveries in the early 1900s, by 1939, that number jumped to 50 percent. By 1945, nearly 80 percent of women gave birth in hospitals. One reason was that urban life, with its cramped living conditions, wasn’t conducive to home births. Another factor was availability of pain medications—you could get them only in a maternity ward.

Although women always have sought relief from the pain of childbirth, in the United States, the first big push for it came during the Suffragist movement. As women organized to fight for social freedoms, they also began to seek freedom from the agony of childbirth. Some of our foremothers would get it around 1914 with the advent of “twilight sleep,” a semiconscious state induced with a combination of morphine and the amnesic scopolamine (closely related to belladonna). Laboring mothers were often dressed in helmets or straightjackets, or tied down with wrist cuffs to protect them from thrashing, and were handed their babies a few hours later. They felt the pain; they just didn’t remember it. If your urban, upper-class ancestor gave birth in the early part of the century, it might have been at one of the many twilight sleep hospitals that popped up in New York, Chicago and Boston.

Society women made twilight sleep births fashionable, and soon the procedure went mainstream. By the late 1930s, half of all women—and 75 percent of urban women—gave birth in hospitals, and they were almost always heavily medicated. Only in the 1970s did popular sentiment push for conscious childbirth.

To learn more about the history of childbirth, read Cassidy’s Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born and Lying-In: A History of Childbirth in America by Richard Wertz (Yale University Press).

Records that Deliver

With all that in mind, you can start hunting down the paper trails of your ancestors’ births.

Birth Records

Birth records hold a wealth of valuable information that can shed light on your ancestors’ birth experiences. When your ancestor gave birth will dictate the type of record—and the amount of information—you’ll find. Birth certificates are the most comprehensive source for your ancestors who gave birth in the late 1800s and after.

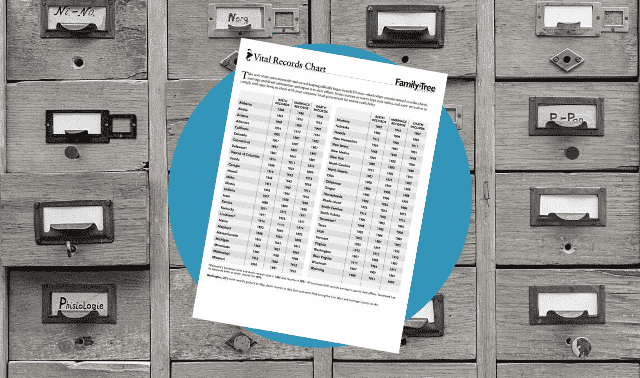

Most states began tracking births systematically and issuing official records around the late 1800s and early 1900s, though some New England towns began recording births as early as 1630. Early certificates aren’t unlike today’s—at the very least, they contain basic information about a birth, such as the child’s name and birth date, the mother’s first and last name (and possibly her maiden name), and the father’s first and last name.

A certificate may note the mother’s age, race, occupation and birth place (and possibly the father’s), the number of children in the family, the location of the birth and any witnesses. Birth certificates usually are available from the vital records office for the state or county where your ancestor was born. Learn more about obtaining them in our State Research Guides.

Before states began requiring birth records, some town and county courthouse clerks recorded births in ledgers. In certain urban areas, local health departments documented vital events. Usually, a father went to the town hall and told the clerk his wife had had a baby, or a midwife or doctor filed a return of birth (a slip of paper documenting his or her attendance at a birth). Returns typically had information not included in the ledger, such as the name of the doctor or midwife. When towns transitioned from ledgers to birth certificates, many ledgers were microfilmed but returns weren’t. Typically, you’ll find microfilmed ledgers at the local courthouse. Not all courthouses have the original returns, but many do—ask the clerk to find out.

Before states began requiring birth records, some town and county courthouse clerks recorded births in ledgers. In certain urban areas, local health departments documented vital events. Usually, a father went to the town hall and told the clerk his wife had had a baby, or a midwife or doctor filed a return of birth (a slip of paper documenting his or her attendance at a birth). Returns typically had information not included in the ledger, such as the name of the doctor or midwife. When towns transitioned from ledgers to birth certificates, many ledgers were microfilmed but returns weren’t. Typically, you’ll find microfilmed ledgers at the local courthouse. Not all courthouses have the original returns, but many do—ask the clerk to find out.

Diaries and Journals

Though few still exist, midwives’ diaries or journals are another valuable resource. Most midwives recorded basic information such as the parents’ names, the sex of the child, date and time of birth, the location of the home and the family’s race. Many midwives also recorded details about the length of the labor, the number of children the mother had, names of other women who assisted, weather observations, distance traveled to get to the mother and payment amount.

The most famous midwife diary is that of Martha Ballard, a midwife and healer who recorded details on the 816 births she attended. Her work is published in A Midwife’s Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary, 1785-1812 by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich (Vintage). You can read, download and search the original diary online at <www.dohistory.org/diary

A search of the local historical society may yield records of lesser-known—but no less prolific—midwives. For example, the diary of Jennet Catlin Boardman (1765-1849), a Hartford, Conn., midwife who delivered more than 1,200 babies over 34 years, survives in readable condition in the archives of the Connecticut Historical Society.

Midwives’ diaries aren’t the only ones that can provide details about your ancestors’ birth experience. Diaries and journals written by regular folks, such as neighbors, can be an excellent source as well. To find such diaries from the 1800s or earlier, try searching WorldCat, the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections or bibliographies of diaries, such as the one created by the one created by the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

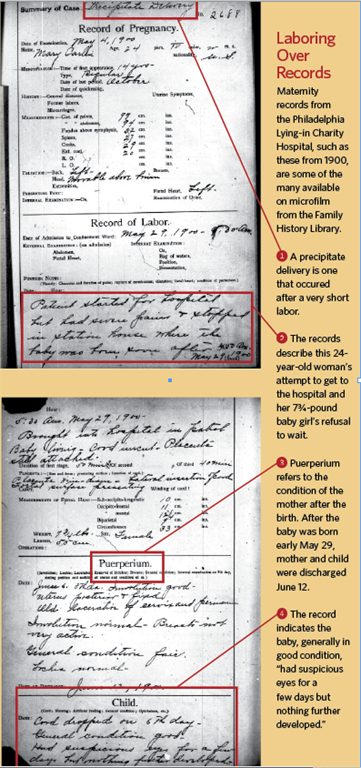

Hospital Records

They may require some effort to hunt down, but hospital records can reveal information about ancestors who gave birth in medical centers. Privacy laws make recent records unavailable, but many institutions let researchers access records more than 75 years old. If your ancestor gave birth in New York City in the late 1800s or early 1900s, for instance, you might find records of her hospital stay in the Cornell Medical Center Archives. The archives holds patient records for the Lying-In Hospital of the City of New York (1893 to 1932), the New York Asylum for Lying-in Women (1854 to 1899) and the Manhattan Maternity and Dispensary (1905-1932). Download a record request form from the archives’ website.

Newspapers

Try checking local newspapers for the name of the midwife who attended your ancestor in labor. Before the 20th century, many newspapers printed birth announcements next to ads for local midwives. You can find newspapers on microfilm at many libraries and historical societies, or search Ancestry.com, GenealogyBank or Google News Archive.

Court Documents

Because midwives of early America weren’t formally trained, few official records name these women. But in early 1700s New York and Virginia, where the English influence was still strong, midwives had to get civil licenses. Midwives were occasionally called on to testify about birth timelines in fornication cases—a search of court records in the town where your ancestor lived might turn up some interesting information. For more on searching court records, see our September 2008 article. Researching your ancestors’ birth experiences may be hard work, but like childbirth, it’s a labor of love.

From the March 2010 Family Tree Magazine

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.