Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Whether it’s your own home, the stately painted lady on the corner, or the dilapidated farmhouse where your great-grandparents raised their eight children—questions start to form in the mind. Genealogists are naturally curious creatures, and we want to know not only about people, but also about the places where they lived their lives. You might wonder who wandered the hallways of your own home before you did. When was that venerable Victorian built? And for whom? What stories does that long-neglected farmhouse hold about your ancestors?

“The house and all its changes allow [you] to physically connect with the stories of families who’ve left nothing behind but the house itself,” says New England house historian Marian Pierre-Louis.

How do you find the answers to these questions? By constructing a house history. Researching the history of a house isn’t that different from doing traditional genealogy. The information and records you need are at many of the same repositories and resources you consult in your family search. I’ll even venture to say there are distinct advantages to researching a subject that stays in place. Families migrate, but with very few exceptions, houses don’t—and that narrows the majority of your search to a specific town or county.

So grab your lunch pail, strap on some work boots and follow this blueprint for building a house history from the ground up.

1. Study the physical house

House histories, like genealogies, start at home, so begin by making careful notes about your research subject. Determining the original date of construction is usually the main focus—but all the changes, additions and renovations that have been made over time are also a part of a house’s past, and you’ll want to include these modifications in your finished house history.

If the house still exists, its exterior can provide a wealth of information about when it was likely built and when major renovations occurred. What’s the architectural style? What materials were used? Is the foundation made of stone, mortared stone, fieldstone or brick? Pay particular attention to the roofline—additions to the original structure often can be identified by their different roof styles. Note the types and layouts of doors and windows. Do the chimneys appear to be original? How many are there, and where are they located? Notice whether neighboring houses appear to be about the same age. Interior details such as ceiling medallions and cove ceilings, though more likely to be removed, covered up or added during restorations, also can provide clues.

Talking to people familiar with the house and its history is another great way to gather clues. Ask longtime neighbors what they remember about the house. If work is being done on the property, ask contractors about hidden features and building materials they’ve discovered. In the course of your research, you might even be able to locate former owners who can provide additional insight.

If the home is no longer standing, use the steps in the rest of this article to find records and images that can enlighten you as to its appearance.

What should your notes tell you about the home’s style and construction? You can find general guides online, but different styles and when they were popular vary locally and regionally. Rely on local, state or region-specific architecture guides from area historical societies and libraries.

2. Find deeds and tax records

Property records provide a strong foundation for your house history. Your first task is to complete a chain of title—the “chain” of owners beginning with the current owner and documenting the purchase of the home from each previous owner. You’ll need to visit the courthouse and search for deed records for the home.

Start with the current owner’s name. Most tax offices let you search for recent assessment and property transfer information using the address and Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping. Using grantor (seller) and grantee (buyer) indexes, work backward from the current owner, one deed at a time. Each deed lists the current grantor, which will be the next name you need to find in the grantee index. Copy each deed you find. If you’re researching your own house, some of this work may have already been done during your purchase, so check your paperwork before visiting the courthouse.

Deeds will provide information about the house and where it’s located, while the list of names and dates you assemble will let you find additional information in tax and other records. You might see that the property was sold, but find no deed recording a purchase. In such instances, title may have passed via inheritance and no deed was recorded. Check wills and probate records to confirm this.

Tax records strengthen the foundation. Unlike censuses, taxes were an annual event, and tax collectors didn’t miss many people. Property tax records may provide information about construction—stating when the house was built or noting major improvements.

In general, the further back your research, the less such detail you’ll find. But analysis of those records may provide some helpful clues. For example, an unusually large jump in assessment from one year to the next is a clue that a house was built or major improvement made that significantly increased the value.

Recent tax records are found at the county or town courthouse, usually in the assessor, auditor or clerk’s office. While at the auditor or assessor’s office, ask if separate transfer histories are maintained for each parcel. These histories, which list details such as changes of ownership, are a huge time-saver when researching chain of title.

Old property tax records might have been removed to storage or to an archive such as a library. Check with the court or local historical society to determine where the records for the area and time frame are located.

3. Seek additional records

With a strong foundation in place, you’re ready to start building on your house history. Both government and private records may provide additional details about the home and neighborhood. Not all of the following records exist in every location, but examples of useful records include:

Building permits

Permits track additions, modifications and other major improvements made to the property. They might provide an owner’s name, original date of construction, details about the existing structure, names of the contractor and architect, and possibly sketches of the building. Building permits are usually held in the city, township or county housing department.

County and local histories

If the house or its former occupants are of historical significance—and sometimes even if they aren’t—you may find references to the home in county, city or neighborhood histories. Even if these books don’t specifically mention the home, they may describe the development of the neighborhood. That context can be important in understanding changes that occurred to the property you’re researching. Two key websites for local histories are FamilySearch books and Google Books.

Insurance records

Fire insurance policies were often required to get a mortgage on a property, and such mortgages may provide clues as to the insurance provider. If you can find insurance records, they can provide details about the number of rooms, construction material, owners’ possessions and possibly sketches.

Extant fire insurance records are most likely in state or local archives and historical societies. They also might be at a local firefighting museum. The many collections at the Pennsylvania Historical Society in Philadelphia and the Mutual Assurance Collection at the Library of Virginia are two excellent examples of what you might find if records exist for your area. If you’re unsure of what companies existed in the time and place you’re researching, try doing a Google search for your city and fire insurance to get names of potential companies.

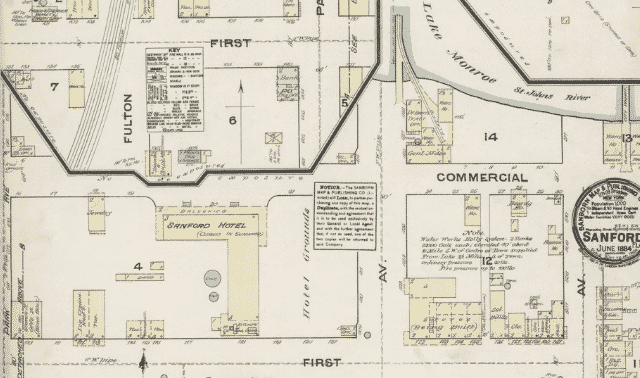

From 1867 to 1977, the Sanborn Map Co. published large-scale maps to help fire insurance companies determine the insurability of buildings. If the home you’re researching is covered, maps will show the building layout and dimensions, construction materials, neighboring structures and more. Large public or university libraries often have Sanborn maps for the local area and may offer them through Proquest’s online Digital Sanborn Maps (1867–1970) database. See holdings at the Library of Congress, with links to some digitized images.

Fire department records

A fire could explain why parts of a house appear more recent than others. Contact the local fire department for more information about extant records. If these records are now at a library or archive, you may be able to locate them by searching WorldCat or the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections.

Utility records

Many older homes predate modern conveniences of water, electricity, gas and telephones. Connections for those utilities made at a later date may form an interesting part of your house history. Water company records are often held by a public entity, but those of other utilities are private. Contact the local utility provider to ask whether historical records exist and where they’re held.

4. Research the house’s residents

Of course, the physical structure is only a part of the house history. “The stories of families bring the history of a house alive in a personal and human way,” explains Pierre-Louis. “It’s magical when you consider that the door you walk through now is the same that another family walked through 100 years ago. The physical house acts as the portal between past and present.”

Changes of family may be connected to changes in the house itself. A home that comfortably held parents and two children might need rooms added on when a family of 12 moves in. Researching a home’s occupants involves familiar genealogical sources. You’ll want to check vital records, church records and other common resources, but a few specific record types reveal more about both people and places:

Census records

Censuses provide such details as who lived in the house, their names and occupations. Depending on the census year, you’ll also learn about the home: its value, whether owned or rented, and how the rest of the neighborhood compared.

Don’t stop with federal population census schedules. Non-population censuses, such as manufacturing and agricultural schedules, can provide details about both people and buildings. State censuses, if they exist for the area, can help trace a family between federal censuses.

Newspapers

The news and society sections can be rich sources of information. The text-searchable newspapers at websites such as GenealogyBank, Ancestry.com and the free Chronicling America have expanded your possibilities for quick and thorough research. In addition to surname searches, try searching for the street name and the specific address. Chronicling America also features a searchable directory of historical newspaper titles back to the 1600s, where they were published and where you can find them on microfilm. Local libraries or state archives are generally your best sources for newspapers covering the area.

Probate records

These records of a deceased person’s estate distribution often are overlooked. “In addition to rich historical information about the families, they also provide estate inventories that list, oftentimes, items that were in the home at the homeowner’s time of death,” says Pierre-Louis, “thus providing a view into the lives of the previous owners.” These records are stored at local probate courts and sometimes state archives, often with microfilm copies available through Family History Centers. Some are even digitized and online at FamilySearch.

5. Supplement with maps, atlases and photographs

Now it’s time to make the place feel more like home. Maps and pictures tell you quite a bit about the history of the home.

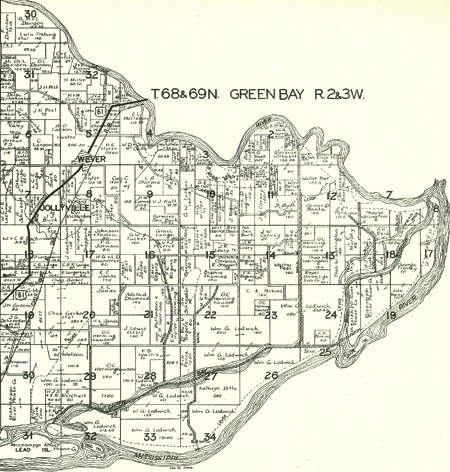

City or county maps and atlases are useful to track changes in properties over time and can clear up confusion caused by changes in street names. Local libraries (both public and university) and historical societies are good sources, as are city, county and township planning offices. Also explore Historic Mapworks and check landowner maps on Ancestry.com.

Historical societies, libraries and archives might have photos of the house or neighborhood. The Library of Congress American Memory collection also has text-searchable maps, atlases and photographs.

6. Share what you’ve learned at an “open house”

You’ve worked hard. Your house history is just about finished, but one more task remains—to let others see what you’ve built by compiling your research. Mention of the word “writing” may cause some anxiety, but this final step needn’t be painful. And the process of assembling, organizing and putting evidence on paper may highlight a mistake, clarify a missing puzzle piece or reveal a previously missed clue.

You could create a timeline of the major events (renovations, fires, new residents) you’ve discovered. This may simplify the process, especially if writing isn’t your thing. If you want more flexibility, go with a narrative approach. Narratives follow no strict chronology, offering more room for creative storytelling and easier incorporation of historical and social context. With either style, add copies of records, photos, maps and newspaper articles, as well as source citations.

If you researched your own or an ancestor’s house, your family would probably be thrilled to receive a printed or digital copy of your work. Also consider donating a printed copy to the local library, historical society and/or town historian. If it’s your house and it qualifies, you even could apply for a listing in national, state or county historic registers. The house itself may one day benefit from your efforts. Faced with a demolition request, local authorities must make a decision. In such cases, a house history could be a “life jacket,” says Pierre-Louis. “Writing the history of a house can be the best way to save it.”

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2013 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated in October 2022.