Have you ever watched “The Bachelorette”? Doesn’t it make you think about your ancestor searches? In case you’ve missed the show, let me explain what I mean.

In the TV series, one woman, the Bachelorette, is searching for her own Mr. Right. She begins with a pool of 25 eligible bachelors. During the next few weeks, she gets to know them, goes on dates and learns about their families. She goes through a process of elimination, narrowing the pool of possibilities for the man who might be her Mr. Right. Finally, during the season finale, she decides which man is right for her and presents him with a rose, hoping he’ll reciprocate by popping the question.

As a genealogist, I’ve looked for Mr. Right, too. Sometimes I find two, three or more eligible men who could be my ancestor. Usually, the men all have the same name and live in the same community. But I go through the same steps as the Bachelorette—minus the dates, of course. I get to know each man, I learn about his family, and through a process of elimination, I narrow the possibilities for my ancestor Mr. Right. As my research progresses, I finally get to a point when I can confidently choose Mr. Right and add him to my family tree.

If you’ve been looking for your Mr. Right, try these nine strategies to pick the rose-worthy one.

1. Note Nicknames and Other Details in an ID Table

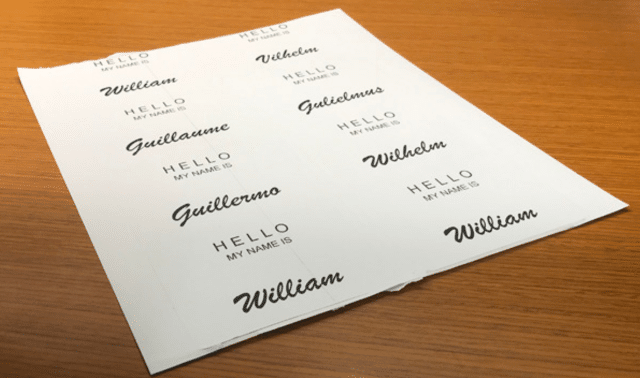

Let’s say you’re at a genealogical society meeting and you meet two men, both named Paul Johnson. How do you keep them straight? Presumably the two men don’t look alike (one has blond hair, the other black; one’s tall, the other short; one’s thin, the other’s chubby), so you rely on physical features to remember which Paul is which.

Realizing that someone else at the meeting shares his name, one of the Pauls might decide to use a nickname. Or other meeting attendees might choose a nickname for him. Our ancestors used nicknames to differentiate themselves, too. In ancient times, particularly before surnames became commonplace, people were known by names such as Eric the Red or Ivan the Terrible. In records, you might notice a nickname designator such as “senior,” “junior,” “the elder” or “the younger.” Indicators such as these should tip you off to the fact that multiple people in a given community share a name.

In The Family Tree Problem Solver, Marsha Hoffman Rising advises readers to always assume that at least two men of the same name were living in each community. Every time you find a record for a man you think is your Mr. Right, ask yourself, “How do I know this record (or this event) pertains to my guy?” This constant questioning helps keep you on track and reminds you to check the record against the facts you’ve already gathered.

Don’t forget that identifiers such as “senior/junior” and “the elder/the younger” didn’t always signify a father/son or other familial relationship. People in the community simply used those nicknames to keep the two men straight. (Are you a fan of “Grey’s Anatomy”? What’s the nickname used to distinguish Dr. Lexie Grey, the younger sister of Dr. Meredith Grey? Give up? It’s Little Grey.)

Now let’s suppose you’re taking an online genealogy class and two men in the class are named Paul Johnson. You don’t have any physical cues to separate the two men in your mind. Unless one decides to be helpful by saying, “Call me Batman,” how else might you distinguish these two men? Perhaps a middle name or middle initial, an occupation, a place of residence, age, marital status or number of children.

These are the same details you’d use to identify your faceless ancestor in records. You might not have a physical description or a nickname, but by sizing him up in the records and gathering every piece of information that might distinguish him, you can create an ancestor profile.

| Paul Johnson | Paul Johnson |

| b. March 4, 1854 | b. April 29, 1855 |

| m. June 3, 1876; wife Mary Murphy | m. Oct. 18, 1880; wife Mary Watters |

| children: Kathleen, Paul, Mary, John | children: David, Anthony, Steven, Nancy, Miranda, William |

| d. Aug. 8, 1900; age 46 | d. Jan. 8, 1935; age 79 |

Make an ID table like the one above, and add identifying information as you research. Having the corresponding details for both men side by side allows you to see at a glance the differences, so you can keep them straight. In addition to vital statistics, you could include other distinguishing details, such as occupation and siblings’ names (see the next strategy).

2. Research Relevant Records

The savvy researcher would never think of claiming someone as Mr. Right before performing a thorough background check. The following records will provide even more details to help you determine if you’ve found your man:

Census records

Start with the most recent census in which a person would be listed (the one right before he died, if you know the death date), and then methodically work backward to his birth, gathering census records for his entire lifetime. Census records are readily available online through websites such as Ancestry.com (by subscription) and FamilySearch (free), or even through the National Archives website, the Family History Library (FHL) and other large genealogy libraries.

Censuses give you a snapshot of an individual and his family in a moment in time. If the guy you’re after is married and has children, take note of the kids. Although two men named Adam Jones may have married women named Susan, it’s highly unlikely they gave their kids the same names or that their kids were born at the same time.

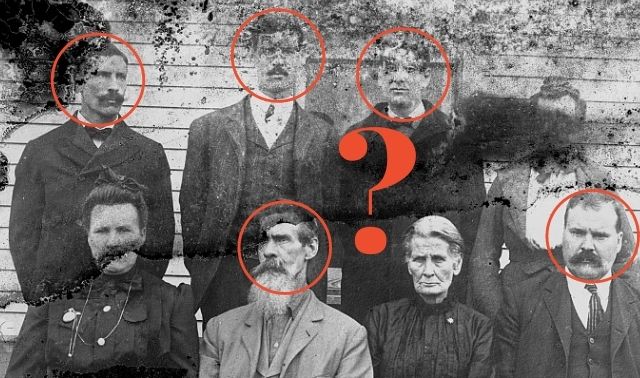

Likewise, when you find two Adam Joneses listed as children in their parents’ households, make note of the siblings’ names. No two men will have brothers and sisters of the same names and ages. Add all these identifiers to your ID table.

Land records

Census research alone may be enough to give you a positive ID for Mr. Right. But if you’re looking for someone who lived prior to the 1850 census, before all household members (except slaves) were listed by name, land deeds will become a critical addition to your search. After all, no two men with the same name—with the possible exception of a father and son—will have owned the same piece of property.

Few county land deeds are available online. Although you may find databases or indexes on the web, they probably won’t contain the details you need to identify someone. Most deeds are indexed; often, counties will have separate indexes for buyers (grantees) and sellers (grantors). You’ll need to look at all the deeds created by the men with the same name.

Let’s say that you find records for two different properties owned by men named Joe Judd. How do you know which piece of land belonged to your ancestor? Make note of who owned the property before and after Joe. If the deed includes neighbors’ names, write those down. Take note of the witnesses. See if any of those names also shows up in your ID table.

Joe Judd Land Deeds

XYZ County, State

| Date | Seller (Grantor) | Buyer (Grantee) | Neighbors | Witnesses | Other Info |

| March 5, 1857 | Joe Judd | Thomas McGraw | Michael Martin Samuel Page David Morrell | John Simon John Zimmer Peter Russell | Joe signed his name. |

| June 28, 1860 | Richard Munroe | Joe Judd | Paul Martin Samuel Treadwell | Michael Jones Thomas Mitchell Abraham Simpson | Joe made his mark. |

| Jan. 14, 1866 | Joe Judd | Charles Atwood | Paul Martin Samuel Treadwell | Thomas Mitchell Charles Ney David Simard | Joe made his mark. |

It may help to create a separate chart listing all the deeds (like the one above) to help you see patterns and sort them out. Notice here that one Joe Judd signed his name, and the other made his mark. Additionally, none of the neighbors or witnesses named in the first deed matches those in the second and third.

As you do more research, watch for the sellers’, buyers’, neighbors’ and witnesses’ names to crop up in other records, connecting them with one of the two Joe Judds. Build your profiles of both men by doing “cluster genealogy.” Emily Anne Croom explains this technique more fully in The Sleuth Book for Genealogists (Genealogical Publishing Co.), but essentially it entails watching for the people who tend to cluster around your ancestor to further identify him. Even cousins who may have had the same name because they were named after a grandparent and were born around the same time in the same locality likely had different friends and associates. These friends and associates often served as witnesses to legal transactions.

Additionally, since deeds are legal instruments and everyone wanted to make sure that ownership was clear, if the county clerk or the person buying or selling land was aware that another man living in the area had the same name, the record may include some kind of identifier—for example, “William Jones, blacksmith,” “Williams Jones Sr.,” “William B. Jones” or “the William Jones who lives on Walnut Creek.”

Some names, such as Sarah/Sallie and Mary/Polly, were so common that a man who married twice may have married two women with the same first name. You might think that Samuel had just one wife named Mary, but a large gap in the births of children or Mary’s having children in her 50s or 60s could suggest that another wife entered the scene. In land records, though, a woman was more likely to be recorded by her full, formal name, rather than a nickname. Sometimes a woman’s maiden name was included to further identify her.

Tax records

Just as with real estate, it’s unlikely that two men with the same name owned the same personal property. Therefore, you can bet that two men with the same name wouldn’t have been taxed on the same items. You won’t find many tax records online. As with land deeds, you’ll need to look for microfilmed copies or published transcriptions of real and personal property tax lists. A table similar to the one for deeds can help you tell the men apart. Also pay attention to the name of the tax collector and his district, as your Mr. Right may have lived in a different district from Mr. Wrong.

3. Scope Out His Address

Your Mr. Right may have lived in one township of the county, while the other guy with the same name lived in another township. But they both would have recorded documents in the same county courthouse. As you search censuses, land deeds and tax records and note neighbors’ names, be sure to write down names of townships, election districts, communities, post offices and any geographical divisions, such as lakes, rivers, valleys or mountain ranges. These are additional identifiers. Use a county map to discover the townships’ boundaries within a county.

4. Pay Attention to Age Indicators

Pay particular attention to the ages of the men you find in your search. As I mentioned before, one may be designated as “senior” or “elder,” which indicates that he is older than the other man. But “older” could be by just a year.

Watch, too, for the absence of this designation. If for several years running you have a John Smith Sr. and a John Smith Jr. and then you find only one John Smith with no identifier, that could be because one of them died, moved away or stopped paying taxes for some reason. But which John Smith died? Don’t assume that it was John Smith Sr. You’ll need to seek additional records to help you sort out who’s gone missing.

5. Research Family Members

Just like the Bachelorette, you should get to know a man’s family before deciding if he’s your Mr. Right. I’ve already mentioned the importance of identifying his wife, kids, parents and siblings. If you’re still scratching your head over which man is your ancestor, dig deeper into the family. Be sure all the connections are solid and that one generation connects to the next and to the previous one. Ask, “What proof do I have that this is a child of Adam Marks?” Analyze each document carefully for all its information. Highlight or mark in red any discrepancy that you find, as this might alert you to another person of the same name.

6. Analyze the Handwriting

Another means of identifying two men of the same name is to compare handwriting, either from a signature or lack thereof. Deeds and wills are the records in which you’re most likely to find a person’s signature. Before you assume that the signature at the end of a will or deed is your ancestor’s, though, compare the handwriting with other signatures in the record book. You may be looking at the clerk’s handwriting. If the signatures are all distinctive, then the signature in question is more likely to be your ancestor’s.

If two Charles Browns lived in the same county at the same time, and one signed his name while the other only made a mark, you’ve got a pretty solid way of distinguishing between them. But that works only if you have other documents that required a signature or mark. This is why it’s important to note neighbors, witnesses and associates in records and to get to know your ancestor’s family.

7. Watch for Inconsistencies and Contradictions

It’s true that people are consistently inconsistent. Yet you still should watch for contradictions and inconsistencies in behavior or patterns as you research. Say the man you believe to be your ancestor has consistently lived in one township his whole life, but you find him witnessing a deed for a person whose name is totally unfamiliar to you from the research you’ve gathered so far, in another township on the other side of the county. Is this your guy? Perhaps not. Perhaps someone new has moved into the county and has the same name as your ancestor.

Say you’re certain your ancestor died in 1848, but you find his name on a deed selling land in 1850. That should send up a red flag. Either you have the wrong death date, or someone else has the same name. Or maybe you find a Civil War record for someone with your ancestor’s name, but your ancestor was 70 during the war. Odds are good this isn’t your ancestor. Don’t forget to do the math. This is when a chronology can help.

8. Make a Timeline

In addition to an ID table, you should make a chronology of every event and document you’ve found for the men of the same name. Record all of the events on one sheet of paper, and then highlight events or details that provide a solid identity or relationship.

If you look at the chronology above, you’ll see that John Riggs had dealings in both Accomack and Northampton counties in Virginia, but there were two John Riggses in these counties’ records. Don’t rule out the possibility that your ancestor had connections in more than one county.

Chronology of John Riggs

| Date | Person | Event | Locality | Comments |

| circa 1701 | John Riggs | Birth (presumably the John Riggs who later married Jemima Melichop) | Presumably the son of Abraham Riggs | |

| Dec. 1735 | John Riggs | Pays fine/cost for Jemima Page; will “bear the Parish harmless for her bastard child” | Accomack County, Va. | |

| Aug. 1736 | John Riggs | Complaint against “negro man owned by John Riggs” | Northampton County, Va. | Negro was ordered to give security to appear at next court. |

| July 1738 | John Riggs Jr. | Southy Rew petitions for Indian corn owed him by John Riggs Jr. | Northampton County, Va. | “The original account was to John Riggs, who assigned to John Riggs Jr.” |

| Feb. 23, 1741 | John Riggs | Land partition | Accomack County, Va. | “John Riggs and Jemima, his wife, late Jemima Melichop, late of Accomack County, spinster.” 216 acres in Pungoteague Neck on Assawoman Creek |

| September 1742 | John Riggs | John was guardian of Absabath Potter and summoned to render an account of his guardianship. | Northampton County, Va. | |

| October 1742 | John Riggs | On a list for a proposed road | Northampton County, Va. | Also on the list is a Peter Kellum. |

| July 1743 | John Riggs | Dispute over line dividing the 88A of land sold to John Riggs of Northampton by Richard Johnson of Accomack | Northampton County, Va. | Papers include the deeds and surveys now in old plat file in clerk’s office in Eastville, Va. |

| Nov. 29, 1743 | John Riggs | Purchased 80 acres from Littleton Eyre | Accomack County, Va./Northampton County, Va. | Littleton Eyre of Northampton County, sold 80 acres and a plantation in Accomack County for 70 pounds to John Riggs, planter, of Northampton County. Land is on the north side of Pungoteague Creek in Accomack. |

9. Try Writing It Out

If you still aren’t able to distinguish between the two men after charting their life events, try writing a biographical sketch of the person in question. As you write out all the details in complete sentences, putting them in narrative form, you should start to see discrepancies. You may realize that the Joseph Reynolds who served in the Revolutionary War couldn’t be your guy after all, because your guy—the one you know is yours because other information is consistent—didn’t arrived in America until after that war ended. That red flag may have been right before your eyes in the chronology, but perhaps you failed to notice it until you started writing your ancestor’s life story.

In genealogy, if not in love, a fear of commitment can be a good thing. Keep asking yourself, “How do I know this is my ancestor?” Explain your reasons in writing, or talk through your logic with another researcher. When you’re sure that you’ve found Mr. Right, you can confidently hand him the rose and place him on your family tree.

How to Avoid Mixing Up Same-Named Ancestors

In The Family Tree Problem Solver (Family Tree Books), Marsha Hoffman Rising describes five common genealogical pitfalls that could lead you to research the wrong family:

- Connecting an event (such as a birth, marriage or death) or a relationship to an individual for no reason except that the name is the same

- Neglecting to search records thoroughly and systematically

- Moving too eagerly to a previous generation before fully exploring the generation you’re currently researching

- Relying on secondary sources, such as undocumented family histories you find in print or online

- Drawing hasty conclusions based on insufficient evidence

Tip: Try using printed census indexes to help you easily find similar surnames and people of the same surname in the same place as your ancestor.

A version of this article originally appeared in the September 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Last updated: Jan 2023

Related Reads

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in affiliate programs through Amazon and Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.