Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The results of DNA testing are important genealogical evidence, much like a census, vital or land record. Any type of record, though, may not provide information about the individual or relationship in question. Sometimes you can’t find a person in the census for a given year, or a person may not have owned any land. Similarly, a DNA test might not help you answer this question, but you won’t know until you run the test and analyze the results.

Sorting similar surnames with DNA testing

Although there’s no guarantee that DNA will provide any insight into your question, there is a good chance that it could be helpful. Accordingly, the first step of this process will be to construct a DNA testing plan that describes the type(s) of DNA test to be taken and the individual(s) to be tested. Every DNA testing plan will be different depending upon the specific facts of the research question. In this case, you should consider both Y-DNA and autosomal DNA as potentially revealing a connection between the Mullin and Mullen families. In order to do that, individuals in both families will have to be tested.

Y-DNA is passed down from father to son, an inheritance pattern that follows the surname is in many cultures around the world. As a result, there’s typically an association between the Y-DNA and the test-taker’s surname. Surname projects take advantage of this association to learn about relationships among those with that name.

So you could approach your research question by testing a male member of the Mullin family with the Mullin surname, and a male member of the Mullen family with the Mullen surname. Comparing those results will potentially help determine whether the two lines are related on the surname line, as you suspect.

It may not be necessary to identify and test a member of the Mullen family, however, if one has already tested. Check existing surname projects for a project of interest. For example, testing company Family Tree DNA lists the Mullen-McMullen Surname Project and the Mullins Surname Project. Together, these groups have hundreds of members who could be potential matches. Although most projects don’t list test-takers’ names, you’ll often see the name and/or location of the most distant paternal ancestor. Use this name to help identify any members of the family who’ve already tested.

DNA Testing Cousins

You may need to locate male members of the Mullin and Mullen families who are willing to test. You can then compare the results of the Mullin test-taker to those of the Mullen test-taker. A close match would strongly support the hypothesis that the two families are related. Together with any traditional documentary evidence, this may give you enough evidence to prove that the families are related.

Nonmatching Y-DNA results weigh against the hypothesis that the Mullin and Mullen families are related—but this doesn’t necessarily disprove the hypothesis. It’s possible that one line experienced a misattributed parentage event, breaking the association between the Y-DNA and the surname. Testing other members of the Mullin or Mullen family can help you check for a misattributed parentage event.

You also might find that the results of the Mullin testing reveal an association with another surname, or may reveal matches with existing Mullin test-takers, thereby providing other research clues.

Autosomal DNA may also help determine whether the Mullen family and Mullin families are related, although at this genealogical distance, the results might be inconclusive.

Because Hamilton Mullin was your great-great-grandfather, any descendants of Hamilton’s siblings would be your fourth cousins, or perhaps your third cousins once removed (these cousins would be of your parent’s generation). Cousins related through Hamilton’s parents or grandparents would be even more distant (fifth and sixth cousins, respectively).

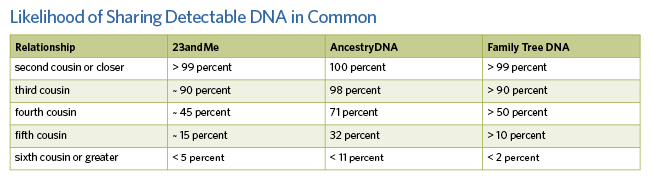

Testing yourself and these potential cousins may reveal shared DNA to help you find the right family for Hamilton. But the likelihood of sharing DNA with a fourth or more-distant cousin is very low. As shown above, the chances you have a detectable segment of DNA in common with a cousin drops drastically after the third cousin level and is even lower for more distant cousins.

Mullin vs. Mullen

If Mullin and Mullen descendants share DNA, that suggests the families are related, although the relationship could be on any of the test-takers’ other family lines. For that reason, you’ll need to do considerable research in genealogical documents to compare the entire family trees of the test-takers. A lack of shared ancestors other than on the Mullin/Mullen lines would support the hypothesis that the families are related on those lines. If they do share lines other than Mullin/Mullen, it’ll be difficult to determine which line was the source of the shared DNA.

What if the Mullin and Mullen descendants you test don’t share DNA? This doesn’t weigh strongly against your hypothesis. If the likelihood of sharing DNA is low anyway, a lack of sharing doesn’t provide helpful information. But testing more people will increase the probability of detecting any shared DNA between the families.

A DNA testing plan will help you determine which tests to use and who could provide the appropriate DNA. For example, a Y-DNA test is best to determine whether two surname lines are related, and you need male-line descendants from each family to test. An autosomal test might be helpful, but the low probability of sharing at this genealogical distance means you must carefully analyze results, and a lack of sharing won’t be meaningful. Together with the traditional evidence, DNA may provide an answer this example question.

Save this article for later: