State government records range from governors’ papers to state land records to records collected by licensing boards. For example, the Records of the Arkansas State Board of Barber Examiners, Deceased Barber Files, 1937-1987 might not raise your heartbeat on first glance. But it’s an amazing collection that traces an entire profession throughout the state. While most of us regularly visit our barber or hair stylist, how many would think to search such records for family history information?

Was your ancestor involved in a profession similarly regulated by a state board? Auctioneers, bail bondsmen, court reporters, dieticians, foresters, medical practitioners, plumbers, embalmers — all were licensed by state boards. If you suspect your ancestor might have been in such a profession, then take a turn off the main record road. Search for and examine those lesser-used records. You may even find a “long lost” photo of your ancestor in some dusty state archive.

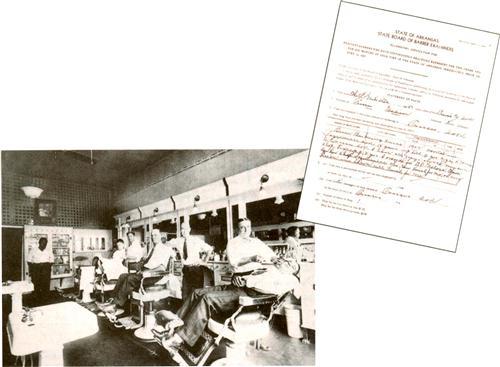

Let’s take those Arkansas barbers, for example. The barber-examiner records are currently available on microfilm in the Arkansas History Commission research room. Looking at them, you can determine basic information including age at the time of application (a clue to the person’s birth date), race, how long your barber ancestor had been in practice, his educational background, whom he worked for and where the barber was located. Since the license was renewed yearly, barbers are easily traced when they moved to new locations, even outside of Arkansas. The file might also include the barber’s actual written test, correspondence between the barber and the board, and copies of obituaries. It may contain medical information, too. Barbers, for example, had to submit to a yearly examination for syphilis, and later tuberculosis, to help prevent the spread of disease.

As a photo archivist, I’m particularly thrilled that the board required each barber to submit two photographs with the application. One was attached to the license and the other stayed with the barber’s file, where you can find it today. Some photos include dates the photo was taken, the photographer’s name and location, and other photographic information such as postcard backs. Sometimes the photo gives a glimpse of the barber’s shop and even parts of the surrounding town.

The Arkansas History Commission’s Stage One Digitization Project is currently digitizing the records and photos of barbers who are no longer active. The commission plans to make the images and their bibliographic records available on its Web site <www.state. ar.us/ahc/> by June 2001.

Who knows what similar treasures might await you in your ancestor’s state records? To start your search, check with the state history commission or archives.