Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

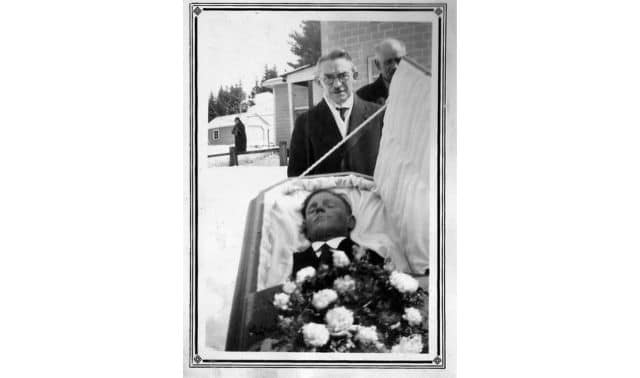

Content warning: This article contains real depictions of death that some may find upsetting.

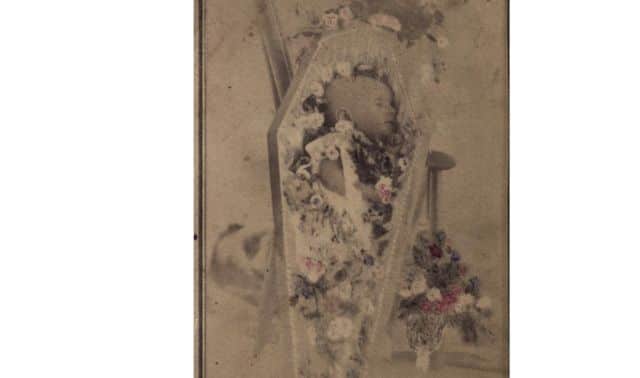

While researching one branch of my family, I came across some old photographs and was startled to discover among them the photo of an infant in a coffin. It was a posed studio portrait. After some little research, I discovered that this was the only photograph taken of a child who had died unexpectedly just months after his birth in 1867.

This striking photo introduced me to the somewhat macabre Victorian-era fashion of post-mortem photography. Victorian post-mortem photography is just one type of memento mori or remembrance keepsake of the dead. It had become highly popular in the nineteenth century at a time when maternal and infant mortality was high and disease could take a life (or many lives) suddenly and unexpectedly. What’s more, because everyday photography was at the time so rare, many saw the remembrance portrait as a necessary way to memorialize a deceased loved one before they were buried left to fading memories.

A number of years ago, my uncle passed away unexpectedly while my parents were traveling outside the country. Since they were unable to return before the funeral, I asked, and was allowed, to take a couple of pictures of my uncle in his casket following the wake for my mother to see when she returned home. I thought that she had later destroyed those photos of her brother but was surprised to learn years afterwards that she had not disposed of them.

Like so many generations before her, that last glimpse of a loved one was something to be treasured and kept. Below, I delve into previous generations’ appreciation for post-mortem photography and what it could reveal to modern-day researchers.

The History of Post-Mortem Photography

Before the invention of photography, history provides many examples of death portraiture in paintings and sketches. The deceased was usually shown as lying in repose upon their death bed, dressed in their finest clothes and artistically arranged to look peaceful and natural. Artists had to work diligently to complete such portraits before natural processes began to deteriorate and degrade the body. Photography, however, made such mementos faster and easier to create and more affordable and accessible to a wider interested patronage. From its earliest development in the first years of Queen Victoria’s reign, the process of photography progressed quickly, becoming associated with that era and with the customs of the times.

Photography is the result of several technical discoveries related to viewing an object and then capturing its image. The first permanent photograph, however, was an image produced in 1822 by the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce. Following his death in 1833, his research partner Louis Daguerre discovered a process that would later be named after him, leading to the invention of modern photography as we know it, notwithstanding similar concurrent research being done around the world at the same time.

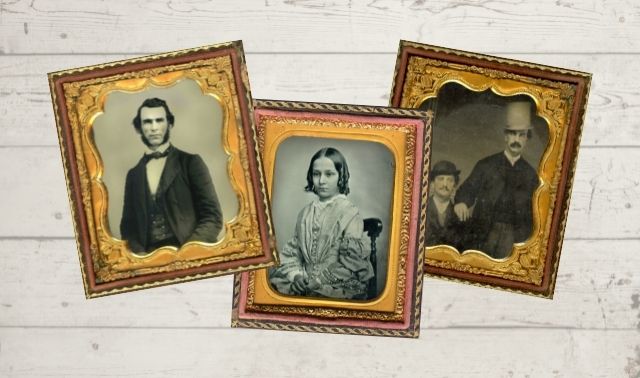

Louis Daguerre publicly revealed his daguerreotype images in 1839, just two years after the ascension of Queen Victoria, and they quickly became popular and increasingly fashionable. Photography as a profession was initiated as these new photographers were hired to portray sitters in a variety of settings and poses. The small but highly detailed images on polished silver were an expensive extravagance, however still not nearly as costly as commissioning a painted portrait.

The immediate success of daguerreotype photography inspired the development and marketing of many other photographic techniques. By the 1850s customers could choose the style of their photographic portrait, from the shiny reflective daguerreotypes to glass ambrotypes or metal tintypes and even paper cardboard photos.

The Process of Traditional Post-Mortem Photography

The advent of photography also paralleled the development of Victorian mourning rituals and customs. Photographers, eager to avail themselves of opportunities to utilize the technology, adopted the advertising slogan “Secure the shadow, ere the substance fades,” the “shadow” referring to the photograph that should be made and the “substance” being a reference to the frailty of the body once inevitable death had begun to decay the flesh. It was a melancholy and pessimistic expression but successful in convincing Victorians that they could preserve images of their loved ones beyond death.

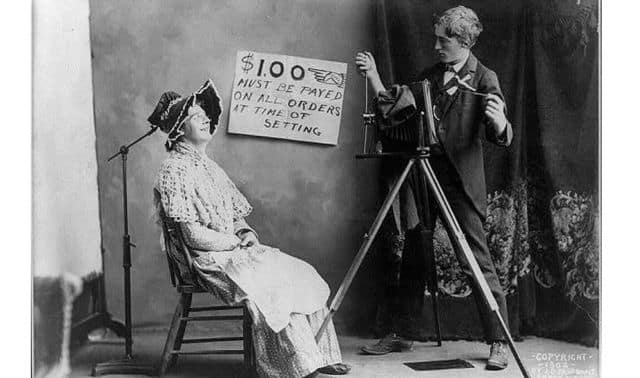

Photographing the dead was a complicated business for photographers, as they had to balance respect for the mourning family with the careful maneuvering of the photographic equipment, the body and props. Often times, photographers could complete the job at their professional studios; however, sometimes, they would have to travel to the home of the deceased, all of their equipment in tow. After the photo session, particularly during the technical reproduction process, the photographer might then also manipulate the negative or even the final print to produce a particularly desired effect.

Post-mortem photographs held a value beyond ordinary photographic portraiture and that value was recognized and reflected in the high fees that were charged. Photographers were, first and foremost, business people who took advantage of the ardent desire of grieving customers to obtain such a specialty service as death portraiture and, as a result, those commissions could be expensive for the family. But as the number of photographers grew and the competition for business soared, the cost of death photography decreased. More efficient procedures and cheaper materials also became available, making such photos more available to a wider economic customer base.

The increased popularity of post-mortem photographs did not lessen their significance, however. For many Victorians, these photographs of the dead were not only a way to cope with grief, they were a way for them to memorialize lost loved ones.

“It is not merely the likeness which is precious,” wrote Victorian-era English poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning about post-mortem portraiture in 1843, “but the association, and the sense of nearness involved in the thing…the very shadow of the person lying there fixed forever! It is the very sanctification of portraits I think- and it is not at all monstrous in me to say…that I would rather have such a memorial of one I dearly loved, than the noblest artist’s work ever produced.”

The Art and Technique Behind Death Photography

Post-mortem photography sought to capture more than merely the image of the deceased. A common technique was the “last sleep,” where the deceased’s eyes were closed and they were posed reclining on a bed, a settee or in the arms of a living family member to provide the impression of peaceful rest. This style played upon the prevalent belief that death was akin to eternal sleep and later similar poses were actually photographed with the deceased ensconced in a coffin or casket. Often the resulting photos were hand-colored or tinted to add a lifelike blush to pale or mottled skin, concealing the realities of illness and death and further enhancing the image of serene and untroubled sleep.

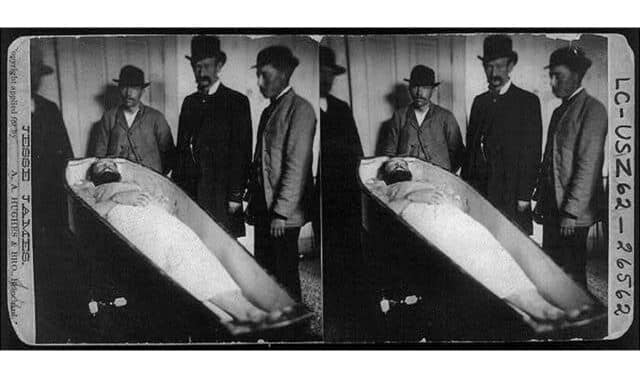

Another technique of death photography attempted to recreate the life that had been lost. Touching scenes known as “mourning tableaux” posed subjects in realistic or lifelike poses, oftentimes seated instead of reclining, and in settings together with living family members or holding a toy or some favorite possession. Often the eyes of the deceased remained open. The style was designed to evoke a recollection of the deceased as they were in life. This would be, after all, the final, if not only, lasting image of the deceased loved one for bereaved customers.

A photograph was often referred to, at the time, as “the mirror with a memory.” This is especially true of death photos that had the specific purpose of capturing and preserving memories for posterity. Such memento mori were kept as keepsakes, prominently displayed in homes, proudly sent to friends and relatives, or kept close to the heart and worn inside lockets or brooch pins and even inset in such regularly used objects as watch covers and pocket mirrors. The introduction of post-mortem photographs into daily life became part of the complex and intricate mourning and memorialization process, much like wearing black clothing, covering mirrors, stopping clocks and other common death traditions.

Society at the time required that mourning be conducted on a grand scale. For this reason, the Victorian period has been nicknamed the “cult of death”. But the strict adherence to detailed customs and elaborate rituals was applied to many elements of nineteenth century life, not only to those surrounding death and burial. For those who could afford the extravagant and expensive observances, and for the middle and working classes who tried to emulate the attitude and etiquette of those more prominent and notable, media like post-mortem photography allowed for the expression of grief in a society that otherwise valued restraint.

Changing Times and Attitudes

Certainly the tradition of memorial portraiture declined in the twentieth century with the development of personal cameras and the increased affordability and accessibility of the process by the masses. The advent of home snapshots decreased the desire for that form of memento mori as most families would have many photographs taken in life. There were still occasional examples of casket photos or funeral photographs but these became less frequent by mid-century, especially as attitudes changed what had been a respected mourning tradition into what seemed to be a macabre and morbid practice. Shifting away from Victorian ideals about death, post-mortem photography has continued as, and currently remains, a valuable tool in medical research, forensic medicine and crime detection and documentation by clinicians, pathologists and investigators.

For many today, the Victorian tradition of post-mortem photography may seem like a gruesome and unsettling gothic custom. But for our ancestors who lived during those times, it was a commonly accepted practice, done with love, dignity and respect. It also afforded years of lasting personal memories. After all, the Victorians did understand the value of celebrating the lives of deceased family members and honoring their memory. Those final images captured loved ones who remained, in death, immortal.

And for those of us who have discovered such mementos in our own family, they provide a glimpse of history that would otherwise be nothing more than a name and some dates as well as a rare insight to the hearts and minds of our ancestors.

Identifying Post-Mortem Photographs

How can you tell if a photo was taken post-mortem? There will usually be several signs that are easy to identify with careful observation. These signs include:

- The subject has a blank expression and off-staring or closed eyes.

- The subject is posed lying down or reclining as though resting or sleeping.

- The subject is posed in an awkward position or propped while seated.

- One subject is cradled or held in position by another.

- The subject may be emaciated, pale or have dark circles around the eyes, signs of recent illness.

- The photo may have been retouched with color added to make cheeks and lips appear rosy and healthy.

- A coffin or a casket would be a dead giveaway.

Where Can You Find Post-Mortem Photographs Related to Your Family?

- Start at home. Look through all your old family photos including albums. Post-mortem photographs can often be found in old albums dating from the first years of the 20th century and earlier—the older the album, the more likely.

- Check with extended family members. Their branch of the family may have possession of photos and albums from a common ancestor or may have received post-mortem photos sent to them at the time.

- Check Local Places. You may have post-mortem photographs of ancestors right at your disposal in your hometown already. Check with the archives of local libraries, museums and other municipal collections where such photos may have been donated.

- Turn to the internet. You might start by posting queries and forum message boards. You never know who might have photos ready to share. Have a look at websites that deal in historical artifacts like eBay, eBid, Etsy, Shopify and other online selling sites. Finally, particular collections of historical mourning and memorial images can be located online at The Thanatos Archive and at The Burns Archive.