Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Jump to:

Researching Immigration Records by Time Period

Records of Foreign-Born Ancestors

Researching Immigrant Neighborhoods

Military Records of Immigrant Ancestors

Naturalization Records

Identifying an immigrant ancestor can be both exciting and intimidating. That foreign country listed on a census or in a vital record may finally explain why your DNA test says you’re 19 percent Irish or give credence to Grandma’s fuzzy recollections about her grandfather’s youth in Russia.

Many researchers, though, immediately feel the urge to “cross the pond” with immigrant ancestors and start looking for records from the “old country.” Linking your family to ancestors abroad certainly is a research challenge and opportunity to relish. But don’t leap the Atlantic (or Pacific) or cross the border too soon. First, you’ll want to find your family in all possible US records. For one thing, to land successfully overseas, you’ll need to know the immigrant’s town of origin, which US records may tell you. For another, ignoring the period of time when an Italian family evolved into an Italian-American family means missing out on a crucial chapter in your family history.

So what kind of records should you look for—beginning with (and going beyond) the passenger arrival manifest? These 17 sources will take you from arrivals to alien registers, from foreign-language newspapers published in US cities to federal military documents. And don’t let the word alien throw you. Your immigrant ancestor was from another country, not another planet (even if he’s been particularly hard to research). That’s just the government’s official term for foreign-born residents who haven’t naturalized. In fact, the more you get into your immigrant ancestors’ records, the less “alien” she’ll be to you.

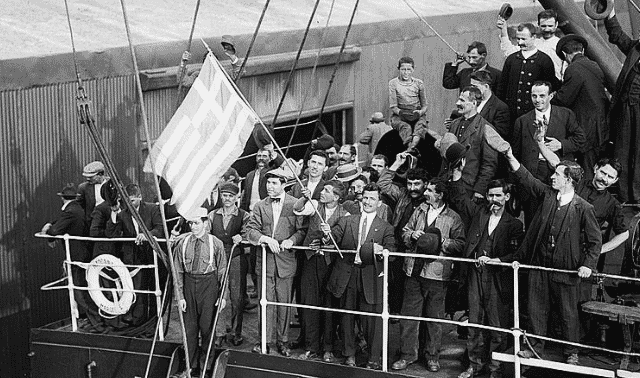

Researching Immigration Records

Whether your immigrant ancestors arrived by sea, land or air, passenger records—created at ports of departure as travelers purchased tickets—may document their first arrival and their return from later visits home. Note that while a passenger record may be your ancestor’s earliest US record, it’s not necessarily the first one to look for. First, learn the names of other immigrant relatives and locate records that point to an arrival date, ship and port. They’ll help you narrow your passenger list search, identify your ancestor with greater confidence and perhaps even spot other relatives onboard.

Collections of passenger records and indexes may be grouped by port, type of arrival and time frame. They break down neatly into three general time periods: pre-1820, 1820 to 1891, and after 1891.

Pre-1820

Before 1820, when the United States mandated recording passengers’ names, passenger arrival records are spotty. Almost all have been transcribed and published in books or databases for various ports or places of origin (Germans, Irish, Scots, etc.). Records may include passengers’ names, ages, years and ports of arrival, and sometimes traveling companions. Many are included in subscription site Ancestry.com’s collection called US and Canada, Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s, which is based on the Passenger and Immigration Lists Index book series by Richard J. Wolfe and P. William Filby. See the box below for more resources.

Hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans were forcibly brought into North America before importing slaves was outlawed in 1808, and the practice continued illegally thereafter. It’s extremely difficult to trace African ancestors far enough into the past to confidently identify first-generation arrivals. It’s even rarer to find ship manifests that enumerated passengers treated as human cargo. Learn more about the early African immigrant experience in books such as The Slave Ship: A Human History by Marcus Rediker (Penguin Books). Another title, Emigrants in Chains by Peter Wilson Coldham (Genealogical Publishing Company), sheds light on the experiences of other forced immigrants during the colonial era, such as convicts, religious nonconformists and vagabonds.

1820 to 1891

Beginning in 1820, arrival ports maintained customs lists with the names of ship and master; port of embarkation; arrival date and port; and name, age, occupation and nationality of each passenger. You also may find information about deaths at sea. These records exist for the major ports of New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and New Orleans, as well as other minor ports. Records are part of indexes and image collections on Ancestry.com and the free FamilySearch. The National Archives’ Access to Archival Databases has searchable indexes covering various nationalities and years (including the Irish Famine era).

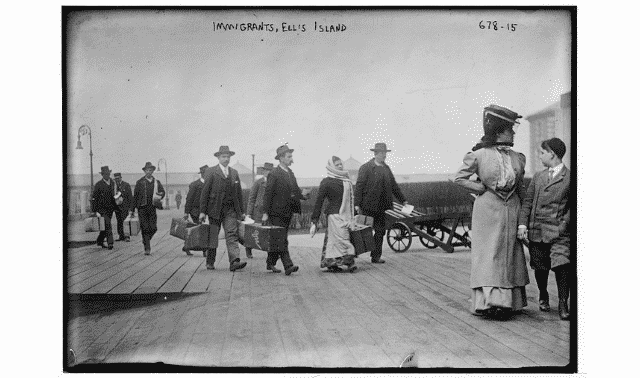

1891 to present

In the early 1890s, the new US Office of Immigration standardized passenger manifests, adding details such as passengers’ previous residence, marital status, prior visits to the United States, final US destination (including name, address and relationship of a relative), literacy status and more. In 1903, race was added; in 1906, a birthplace and physical description; and in 1907, the name and address of the closest living relative in the home country.

Find many passenger lists dating up to about the 1960s on major genealogy websites such as FamilySearch, Ancestry.com, and subscription sites Findmypast and MyHeritage. Try these free websites, too: Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild, and for the Port of New York, CastleGarden.org (1820–1892) and Ellis-Island.org. If you know the port of origin of your ancestor’s journey, you also might search for emigration (or outgoing) passenger lists from that country and port.

Your relatives may have arrived (or left) by road or rail at the Canadian or Mexican border. Consistent border crossing records weren’t kept by the United States until around 1895 or by Canada until 1908. Records don’t exist for every point of entry, but millions of border crossings with are available to search at Ancestry.com and FamilySearch. In the 1900s, you also may find arrivals by airplane in databases on the same sites.

Records of Foreign-Born Ancestors

Before World War I, the federal government didn’t keep close tabs on alien residents. But in the first two decades of the 1900s, the number of foreign-born was at an all-time high, and global warfare began. Some Americans eyed with suspicion their neighbors of German, Japanese or other “enemy alien” origin. A new paper trail began to document noncitizen residents. You may discover documents such as:

1. Enemy alien registration affidavits, 1917 to 1918

When the nation entered World War I, president Woodrow Wilson issued an executive order requiring German, Japanese, Italian and other aliens—and women married to them—to register at the county level. Some of these detailed documents exist in local or state repositories and at the National Archives. For example, San Francisco affidavits are on FamilySearch and the National Archives in Kansas City, Mo., has affidavits for Kansas. Some are accessible in the National Archives catalog.

2. Visa files, 1924 to 1944

As a result of new quotas on numbers of immigrants from various nations, US embassies overseas began issuing visas in 1924. Those who wished to become permanent residents applied for immigrant visas; others applied for temporary or nonimmigrant visas. (Children generally traveled on a parent’s visa.) References to visas often appear on passenger lists during this time period. Travelers’ visas were filed at the INS along with any additional documentation. Order copies through the US Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Genealogy Program.

3. Registry files, 1929 to 1944

These files fill the gap for arrivals in the United States before mid-1924 (when the visa program began) for whom officials could later find no arrival record. The files often include evidence of that person’s arrival and US residence. Order copies through the USCIS Genealogy Program.

4. Alien registration (AR-2) forms, 1940 to 1944

During the WWII era, aliens older than 14 had to register at local post offices or upon entering the country. They were assigned alien registration numbers and carried receipts to prove they were lawfully registered. Order copies of microfilmed forms through the USCIS Genealogy Program.

5. Internment camp files

“Enemy aliens”—and sometimes their US-citizen relatives—were incarcerated during both World Wars. This wasn’t a widespread practice in World War I, although more than 2,000 Germans were detained in camps. More infamously, during World War II the federal government detained about 120,000 Japanese citizens and Japanese-Americans in war relocation camps. The National Archives has a free searchable database of inmate files, where you also can learn about War Relocation Authority records.

The Immigration and Naturalization Service also interned more than 30,000 enemy aliens, including those of German and Italian descent, who lived across the United States and in several Latin American countries. Records of those camps are at the National Archives (part of Record Group 85), as are records of the Alien Enemy Information Bureau relating to civilian detainees (Record Group 389). Some Federal Bureau of Investigation files on alien enemy detentions are in the FBI’s digital Vault (search for the subject Custodial Detention).

6. Alien case files, 1944 to the present

These “A-files” are compiled for nonnaturalized immigrants since World War II. Organized by alien registration number, these include AR-2 forms, other pre-naturalization documents and naturalization paperwork (if naturalized after April 1, 1956). Original case files are at National Archives offices in Kansas City, Mo., and San Bruno, Calif. You’ll find an index to alien case files through 2003 for those born before 1909 at Ancestry.com. Order files dated April 1, 1944, to May 1, 1951, through the USCIS Genealogy Program. Learn more about alien case files and related documents.

Researching Immigrant Neighborhoods

Since colonial days, immigrants with shared heritage have clustered together in ethnic enclaves and communities. Many have acquired nicknames, such as New York’s Little Italy, San Francisco’s Chinatown and Cincinnati’s Over the Rhine. Here they found support and the ability to shop, worship, go to school and socialize according to their own traditions and languages. These communities may produce records that point to overseas origins and reveal insights into the transitional time between arrival and assimilation.

Records created by or about immigrant communities are often in their native tongue. Google Translate can help with simple phrases. Genealogy word lists found in the FamilySearch Wiki also may prove useful, especially for the Latin script found in some church records.

7. Church records

Millions of immigrants brought their faiths with them across the sea and flocked to ethnic churches: Norwegian Lutheran, Dutch Reformed, German Baptist Brethren. By the late 1800s, Catholic national or ethnic parishes became more common, too. Poles, Slovaks, Italians, Germans, Irish and other Catholics all were (understandably) happier worshiping with others who adored the same saints, ate the same food and prayed in the same language.

Membership and sacramental records of these churches may report the exact overseas birthplaces of immigrant members. Many pre-printed Catholic baptismal registers in use by the late 1800s had a place to record the birthplace of a baby’s parents. Some Protestant faiths accepted letters of transfer from new members. The letter itself (if kept) or notations in membership registers or minutes may state the prior residence. Church records aren’t always easy to find. Try these strategies:

- If the church still exists, check with its office first. Run a search in your web browser for the name of the church and/or denomination and the location.

- If the church has closed or no longer has its old records, look to regional or central church offices or archives, regional and university archives, and local genealogical and historical societies. Your ancestor’s congregation may have merged with another or sent its records elsewhere to be archived.

- Search for microfilmed or published church records. For materials in libraries, search the WorldCat catalog; for original records in archives, use ArchiveGrid. If records were transcribed in a journal or newsletter, they may be listed in the Periodical Source Index (PERSI) at Findmypast.

- Try genealogy websites. Ancestry.com hosts large collections of Dutch Reformed/Dutch Christian, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, Quaker and Methodist records. Findmypast has launched the Catholic Heritage Archive with a growing number of baptismal, marriage and death/burial records.

8. Foreign-language newspapers

Unless they became famous or infamous, your immigrant ancestors were more likely to have their names appear in newspapers aimed at their own communities than in mainstream newspapers. You may find obituaries, wedding or anniversary announcements, birth notices, professional profiles, travel accounts and even “missing persons” messages from immigrants trying to locate relatives. Obituaries can be especially rich resources, providing the most complete surviving biographical sketch of an immigrant’s life. Of course, you’ll need to enter search terms and names in the language of the newspaper. Also try browsing issues published around births, deaths and other family events.

Research guides for ethnicities or locales of interest may suggest papers (as well as other ethnic resources) to consult. Digitized collections on subscription site GenealogyBank include some German-, French-, Italian- and Spanish-language papers; Newspapers.com holds German titles. The Library of Congress’ Chronicling America website lists newspapers published in nearly 100 languages. From the home page, click on US Newspaper Directory to search the most comprehensive list of newspaper titles available by place, time period, language and other criteria. Then search the catalog listings there and at WorldCat for print, microfilmed and other copies of the newspapers you want. Some editions may be digitized on the site.

Offline, local libraries may house back issues of locally published foreign language and other papers. The Immigration History Research Center (IHRC) in Minneapolis has collections that include many foreign-language newspapers. Browse its Periodicals section by language; you can visit or submit a research request.

9. Society records

Immigrants formed charitable societies and banks to provide insurance and help their fellow countrymen with the financial and logistical challenges of coming to the United States. Fraternal organizations and social clubs, such as the Swiss or German turners (gymnasts) or Jewish community centers, helped immigrants preserve their culture.

You might catch a glimpse of a family name or face in photos, published histories or news clippings about these groups, or just learn basic information about the group as a whole. A note that many of the group’s members hailed from a specific town in Italy or Poland, for example, would be valuable.

It’s possible you’ll get lucky and locate surviving membership lists or files. Use strategies similar to searching for church and other original records. If the organization still exists, ask at its office. Search online for collections of original records in libraries and for published books or articles, and contact the IHRC and local repositories. You might find a few indexes online, such as Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society records on Ancestry.com.

Military Records of Immigrant Ancestors

Noncitizens have served in American military forces since colonial days. In fact, expedited citizenship has been—and still is—offered as a perk to qualifying immigrants. In addition to regular military enlistment, service and pension documents, look for foreign-born ancestors in draft registrations, which record even men who didn’t serve.

10. Draft registrations

The federal government registered potential conscripts—including eligible aliens—during the Civil War, World War I, World War II and afterward. In more recent draft registrations, you’ll find a 4-C classification for alien or dual nationals, who are sometimes exempt from service.

11. Civil War records

Search surviving registers on Ancestry.com. They don’t routinely note overseas birthplaces or citizenship details, though.

12. World War I records

Draft registration cards give naturalization status and country of citizenship; the second draft (for men born from about 1886 to 1900) also requested specific birthplaces. Search WWI draft cards free at FamilySearch; they’re also at Ancestry.com, Fold3 and Findmypast.

13. World War II records

Cards include birthplaces but not citizenship status. Find available cards on Ancestry.com, Fold3 and FamilySearch (for birthdates (April 28, 1877, to Feb. 16, 1897). Order cards for men born from Feb. 17, 1897, to July 31, 1927, following instructions on the National Archives website. Aliens also may have filled out personal history forms and/or applied for exemption from service; many states’ records are part of National Archives Record Group 147. Scattered collections are online, such as a few states’ records at Ancestry.com and others at German Genealogy Group (under Naturalizations).

14. Post-World War II records

For men born 1897 to 1957, request copies of draft registrations using the link above. You’ll need the full name of the applicant and his address at time of registration.

15. Case Files on Drafted Aliens

This special group of records exists for noncitizens who were drafted into the Civil War and were subsequently released from service. A case file may include a draft notice, depositions regarding foreign citizenship and official correspondence relating to releases. Find these at the National Archives (part of Record Group 59).

16. Enrollment lists

Thousands of immigrant men served as paid substitutes for Civil War draftees. Details may appear under the draftee’s name on original descriptive or enrollment registers. The National Archives maintains these documents by state and congressional district in Record Group 110.3.1; search for additional collections using ArchiveGrid or your web browser. Enter the name of state or the congressional district and the keywords civil war, descriptive or enrollment.

17. Military naturalization petitions

Beginning with the Civil War, honorably discharged noncitizen veterans age 21 or older could petition for citizenship without the usual first round of paperwork (the declaration of intention) or waiting period. These military naturalizations may have been filed like other naturalizations, but many county courthouses have separate volumes for military naturalization petitions. You can find a few military naturalization collections indexed online. An index to those for World War I is at FamilySearch. Ancestry.com and Fold3. Ancestry.com has a few indexes for World War II and the Korean War. Find other scattered indexes at such sites as the German Genealogy Group and ItalianGen.

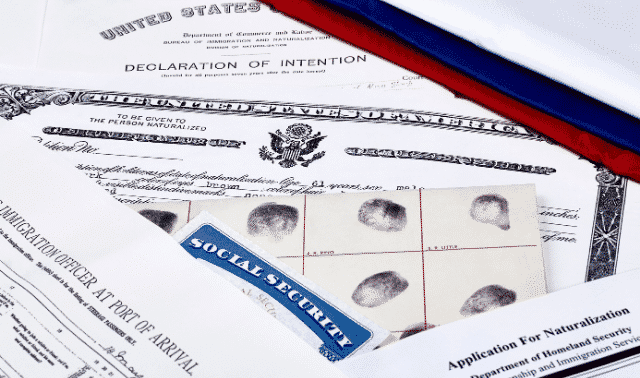

Naturalization Records

Not all immigrants became citizens. For some, the perceived benefits weren’t worth the effort. Others wanted to maintain official loyalty to their homelands. Some weren’t eligible. Until 1922, immigrant family members derived their citizenship from that of a husband or father. From 1907 until 1922, a female citizen who married an alien man lost her citizenship. Today, just under half of US immigrants have naturalized.

But for many immigrant ancestors, citizenship is another chapter in their lives—and uncovering their petition to naturalize, oath of allegiance and declaration of naturalization is another chapter in your genealogical discovery. Immigrants could file these records in any court of record. Starting in 1906, courts used standardized forms that were forwarded to the federal government. Ancestry.com, Family-Search and Fold3 have many naturalization record indexes and images, and you can order records from 1906 and later through the aforementioned USCIS Genealogy Program. To learn more, turn to our Naturalization Records Workbook, which appeared in the downloadable September 2015 Family Tree Magazine.

After searching in these American-made records, you’ll be better prepared to cross the pond to your ancestral homeland. You’ll likely have a better idea where you’re heading and who you’re looking for. And you’ll certainly carry with you a much better appreciation of what it meant to be a stranger—an alien, even—in a new land.

More Resources

- American Passenger Arrival Records: A Guide to Immigrants Arriving at American Ports by Sail and Steam, revised ed., by Michael Tepper (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Angel Island

- A Bibliography of Ship Passenger Lists, 1538–1825 by Richard J. Wolfe (New York Public Library)

- Castle Garden

- Ellis Island

- Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins by Loretto Dennis Szucs (Ancestry)

- Emigrants in Chains by Peter Wilson Coldham (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Immigration History Research Center Archives

- Passenger and Immigration Lists Bibliography, 1538-1900by P. William Filby (Gale Research Co.)

- National Archives

- The Slave Ship: A Human History by Marcus Rediker (Penguin Books)

- They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins by Loretto Dennis Szucs (Ancestry)

- They Came in Ships by John P. Colletta (Ancestry)

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2017 issue of Family Tree Magazine.