Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

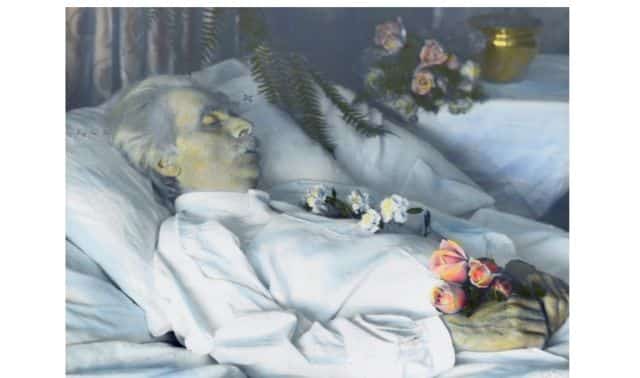

Content warning: This article contains real depictions of death that some may find upsetting.

Family memorabilia and the trappings of past lifetimes live on in attics, basements, closets and storerooms. They exist in limbo: no longer wanted or used by the family, but unable to be thrown away. But that detritus may contain many genealogical riches—maybe even heirlooms of surprising value. Amid the trunks, old clothes and unused furniture are sure to be wonderful treasures and unexpected curios.

A family Bible, old journals or framed portraits have obvious utility to family history. But what will you do with a box full of funeral cards? Or an album of morbid post-mortem photographs? Or a strange framed wreath that looks like it was made from … hair?

The Latin phrase Memento mori comes to mind: “Don’t forget that you have to die.” Philosophers and theologians encourage reflecting on mortality—the certainty of death—to motivate and inspire your life.

Preoccupation with death reached its peak in the Victorian era, when elaborate rituals surrounding death were practiced by all levels of society. Many relics of that time have survived even as society has lost its taste for the macabre and morbid.

Throughout this article, we’ll look at some examples of memento mori heirlooms that may live in your attics and cellars. And we’ll consider the value they have to modern genealogists.

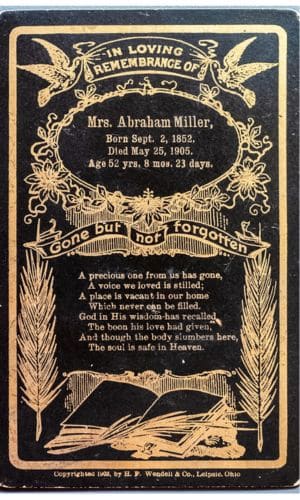

Mourning, Mass and Memorial Cards

From Victorian times to today, mourners have commissioned and printed funeral cards for various purposes. These cards originally informed family and friends of a person’s death and of upcoming funeral and burial services—or conveyed the news to those loved ones too far away to attend the memorial.

But they often had artistic elements, too, with elaborate designs, poetry or scripture verses. And genealogists will appreciate birth dates and places, death dates and places, and occasional names of family members. Most funeral and memorial cards were small and rectangular, usually about 3×4 inches and printed on various thicknesses of card stock paper. A thick black border around the card was the standard indicator of mourning.

Later, funeral cards were created as memorial keepsakes, intended for display and distributed widely at the wake, funeral, interment and luncheon as favors. They may have been a larger size, appropriate for framing, and included a photograph of the deceased.

These are excellent sources of family connections, and can lead to funeral homes, churches and cemeteries. Digitize and preserve these cards as you find them—and hang on to cards you receive at funeral services yourself.

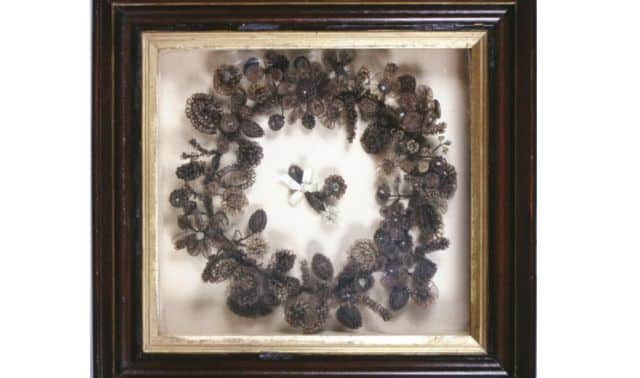

Hair Wreaths and Jewelry

Animal and human hair alike have long been used in household furnishings: furniture cushions, pincushions and pillows. But it was in the Victorian era that hairwork crafts became a form of lasting artwork, too.

Loved ones and relatives often gave locks of hair as tokens of friendship, personal connection and love. These could then be braided and placed in a locked, mounted, bent around a wire into a variety of shapes or even framed. Because it outlasted the donor, hair became a tangible keepsake of a departed loved one. In fact, whole books were written to provide instruction on creating works of art from hair: wreaths, floral designs and jewelry. (The latter was one of the few adornments permitted by strict mourning customs.)

Today, we may admire these crafts as beautiful until learning they’re made of human hair. (As with some other mementoes we’ll discuss, they’re often seen as macabre through a modern lens.) But their genealogical intrigue remains.

Note that current technology requires the roots of hair to test for genetic genealogy—and most clippings were cut far from the root. But in the near future we may be able to test any section of hair for genealogically useful DNA, opening up new avenues of research.

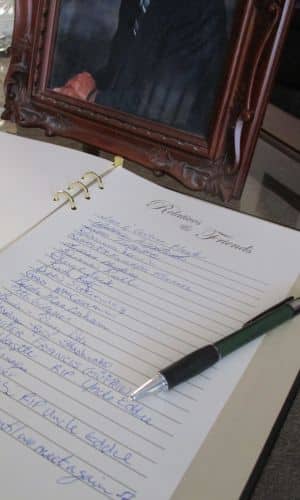

Funeral Guest Books

These are another kind of heirloom still created today, albeit less frequently than they once were. Such books hold the names of guests at a funeral service—often relatives (both close and distant), friends, neighbors and business associates.

With the right attitude, you can use funeral guest books as a kind of directory of the deceased’s social network. Each name is a valuable lead in your research, and comments might provide clues to the deceased’s personality. They’ll also provide a treasure trove of autographs, which are heirlooms in their own right.

Post-Mortem and Funeral Photography

Thanks to digital cameras and smartphones, we have so many photos of ourselves and our loved ones—even of our pets. But when photography was first invented in the Victorian era, being photographed was a once-in-a-lifetime event for some people. In fact, loved ones may not have had a photo of a person.

Photographers were quick to develop a business around this need. Post-mortem photography—photos taken after a person’s death—were the result, capturing departed relatives for posterity. Though grim to a modern audience, this commonly accepted practice was done with love and retained the deceased’s dignity.

It afforded years of lasting personal memories to those the deceased left behind. After all, Victorians keenly understood the value of celebrating the lives of deceased family members and honoring their memory. Like other memento mori heirlooms, these were intended as keepsakes: prominently displayed in homes, proudly sent to relatives or kept close to the heart inside lockets, brooch pins or even insets in watch covers and pocket mirrors.

Coffin Plates

These adornments are usually made from soft, easily engravable metal such as lead, pewter, tin, copper, brass or silver. They were often engraved with the deceased’s name, death date and age. But other messages could include different details or simple endearments such as “Our Darling” or “Baby.” The plates were then nailed to the lid of a wooden coffin for funeral services, removed before burial and kept by loved ones.

Once reserved for the rich, coffin plates became common at all levels of society. Like other memento mori heirlooms, they may have been displayed in the home in a frame or on a mantelpiece or table. Coffin plates today are sometimes required in order to identify the deceased for transportation, burial or cremation. However, they’re rarely removed and kept as keepsakes.

Don’t rush to get rid of these or similar strange, morbid, wonderful collectibles. That attic, basement or closet may hold a cache of relics for generations to come.

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2024 issue of Family Tree Magazine