Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

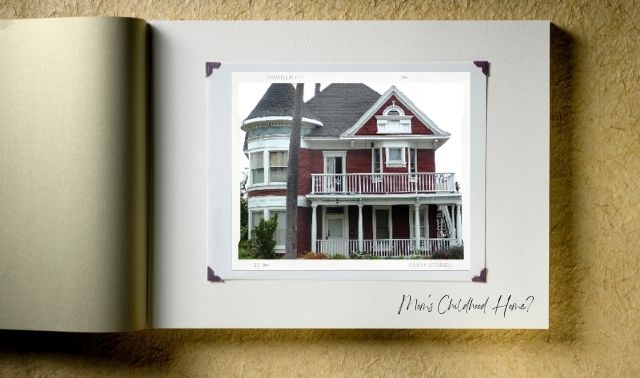

Wouldn’t it be terrific if we could read between those handwritten lines in census records in order to answer our nagging family history questions? When the 1940 US census was first released and I eagerly examined the records for my mom’s parents, I expected to find them living in the grand old Victorian house Mom often pointed out as her childhood home. But instead, they showed up in a more modest house a few miles away.

Many of our parents and grandparents—and even some of us—are represented in the most recent publicly available census, taken in 1940, giving us access to all kinds of information about everyday life at the time. And nearly 75 years later, many of us also have inherited family keepsakes and household miscellany from those same parents and grandparents who appear in that enumeration. Add the clues from these items to the ones in the 1940 census, and you can read quite a lot between the lines of the census.

Today, the Victorian stands on a busy Santa Ana street, with a wide lawn and stately turret that make it a local landmark. I wondered: Did Mom really live in that house? How could my grandparents, who didn’t own a home and moved frequently—Grandpa traded home repairs for rent—afford to live for any length of time in such a large and elegant old house? The answer was hidden in the census. The same four strategies I used to read between the lines of the census and discover surprising facts about my grandparents’ resourcefulness can help you unlock clues to solve family mysteries, too.

1. Target the right census.

Census information is the backbone of genealogy research, and the 1940 US census is one of the richest surveys of all for family history data. If you’re looking for answers about a particular aspect of your ancestor’s life, it’s helpful to home in on a specific census during his life that highlights pertinent questions. I turned to the 1940 US census, with its wealth of Great Depression-prompted employment data, to get a handle on my grandparents’ living situation and whether they indeed could have lived at some point in the big house my mother remembered.

Census surveys have always reflected the signs of the times, whether the government wanted stats on males eligible for military service, massive immigration, literacy or the population shift from rural to urban life. Like many men, my grandfather had a tough time finding work between 1930 and 1940. The Census Bureau was especially interested in discovering how well Americans were doing economically in the wake of the Great Depression, and more than a quarter of the questions on the 1940 census dealt with employment status and wages. Other questions asked about internal migration, including where Americans lived in 1935 and if they were at the same address April 1, 1940 (the official census day). I started my investigation with the 1940 census employment data.

2. Transcribe, extract and analyze.

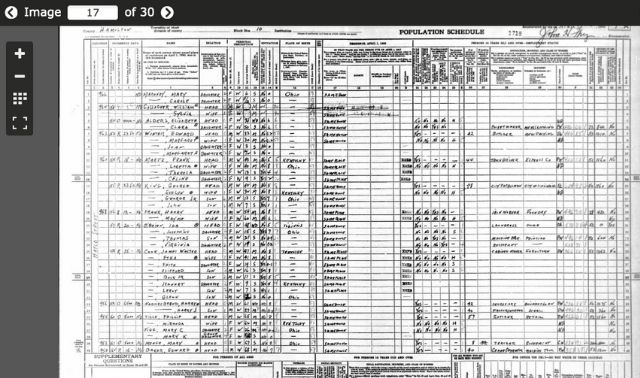

Squeeze every drop of information from census records by transcribing—copying word for word—the information on the sheets. Because census data are presented in table format, I like to transcribe the information the same way using a chart or spreadsheet with columns labeled the same way as on the census.

When I find an obvious error—for example, a household member’s first name is spelled wrong—I copy the word as it appears and indicate the correct word in brackets: Suzannah [Susan]. If a word is illegible, I write [illeg] so I know information wasn’t skipped.

After transcribing the Frank Brown household information, I copied the details into my genealogy database software. Next, I made a list of information that generated comments and questions for future research. I wanted to discover when the Browns lived on North Broadway, so I marked with an asterisk any clues that might be helpful with that research. You can see my chart below.

| 1940 Census Information | Notes and Questions |

|---|---|

| 1940 Census Information | Notes and Questions |

| On April 9 (the day the census taker visited), Frank A. Brown was the head of household, renting the house at 1021 E. Cypress for $25 per month. | • Where is 1021 E. Cypress? Locate it on a map. • What is average rent in the neighborhood? |

| Frank was a white male, age 47, who attended school through eighth grade. | |

| He was married to Arline A., age 49. He had two daughters, Frances L., age 9, and Suzanne W. (my mom), age 7. | • When did Frank and Arline marry? Possibly 1930 or 1931. |

| Frank was born in California (in 1893, estimating from his stated age). | • Birth information confirmed by birth record. |

| In 1935, Frank and family lived in Kansas City, Saline County, Kan. They didn’t live on a farm. | • How long did the family live in Kansas City? |

| For the week of March 24-30, 1940, Frank didn’t work in any capacity. He was seeking work and had been unemployed for 78 weeks prior to March 30 (on the census return, 18 mo. is lined out and 78 is penciled above). Frank was a cannery worker by trade. He hadn’t worked in 1939. His wages that year were $0, but he had other sources of income totaling over $50. | • Was unemployment common in the neighborhood? • What other sources of income did Frank have? |

Like many Americans of their era, my grandparents left their home in Kansas to look for employment and opportunity in California. Mom remembered living in the old Victorian house at 1315 N. Broadway sometime in the 1940s, but the census showed they weren’t living there on the April 9, 1940 survey date.

I transferred the non-asterisked notes and questions to my genealogy to-do list for later research. (My genealogy software has a to-do list feature; another option for tracking to-dos is the Research Planner and Log.) Then I got to work on my prioritized questions.

3. Understand the neighborhood.

I used the web to find the exact location of the Brown home on Cypress. Typing the street address and town name into Google brought up a map of the location on Google Maps. With Street View, I could get a close-up look at the house. Then I hit Get Directions to find the distance between this house and the other one. The Browns’ 1940 home at 1021 Cypress was 1.6 miles from the house Mom remembered at 1315 N. Broadway.

Next, I looked closely at the families in their neighborhood. By comparing the Brown family with a dozen or more households listed near them in the census, I was able to see how my family fit within the economic and social sphere of their neighbors.

A quick tally showed that about half the families in this working-class neighborhood were homeowners, and half were renters. But only a few families paid more rent than my grandparents’ $25 monthly; most paid between $10 and $20 a month. It also seemed to be a fairly stable neighborhood, with most residents living at the same address five years earlier (a data point noted in the 1940 census).

The Browns were typical for the time and place. Their neighbors were a mix of native Californians and newcomers born in Texas, Iowa, Germany and many other places. Times were tough in 1940s Southern California; my grandfather wasn’t alone in his long unemployment. Many of his neighbors didn’t have jobs, either.

After extracting information from the census and evaluating my relatives’ place in the neighborhood, I still had some questions:

- Why was the Brown’s rent higher than their neighbors’ rent?

- What was Frank’s other source of income?

- When did the family move to the Victorian house at 1315 N. Broadway?

- How could the Browns possibly afford the rent on the larger house?

To conduct your own neighborhood survey, use a tally sheet that includes the key data items you want to examine. Locate the residence on a map and draw a border around the neighborhood. The typical neighborhood was usually an area of several blocks that included a grocery store, school and church. By 1940, many rural and suburban families owned a car, and their community was even wider, but people still often chose their residence near friends, family, church and school.

Start with the next-door and across-the-street neighbors for your target family. Extend your sample to at least two or three city blocks or several miles in a rural area. You’ll want a few dozen households in each direction to get a sense of your family’s neighborhood.

4. Look beyond the census.

The first stop for any type of family history research is your own home and the homes of your relatives. I’ve inherited a trove of letters, photos and assorted memorabilia from my mother, aunt and grandparents. It’s easy to recognize the genealogical value in old letters and photos, but harder to know what information you can learn from old bank passbooks, ration books, library cards and the like. I was glad I saved those things when I began to tackle this research problem. I wanted evidence of residence—where the Brown family lived in the decade following the official 1940 census.

The answer to my questions was in my family archive. I pulled out a box of old financial records left in my grandparents’ estate and started looking for any papers dated in the 1940s.

I started with letters, looking at the address, return address and postmark to discover where Frank, Arline, Frances and Suzanne lived. I found several different addresses for members of the family. To organize the information, I created a timeline of dates, names and addresses. Next, I looked at other items that might hold clues to a residence: address books, ration cards, membership cards. Here’s a list of helpful items you may have inherited:

- appointment calendars

- auto insurance or registration papers

- bank account passbooks

- driver’s licenses, library cards, club memberships and other identification cards

- household bills and receipts

- letters

- magazines (look for an address label)

- paycheck stubs

- ration books

- rent and mortgage receipts

- school or medical paperwork

- tax returns

- utility bills

I was surprised to find a small book with the title Money Receipts, the kind used by landlords in collecting rent. The book runs from January 1944 to November 1945, and includes stubs of receipts for weekly room rent, amounting to $5 and $7. Were my grandparents bootlegger-landlords who were subletting the garage?

Next, I found a loose, torn receipt made out to my grandfather and dated Sept. 1, 1942. It was for payment of $25 rent for a house on Broadway.

The clues all fell into place with two more items: a carbon copy of a typed letter from the Office of Price Administration, dated May 20, 1943, denying the landlord’s petition to evict my grandparents, as well as a handwritten Tenant’s Complaint signed by my grandmother one week later.

It looks like Arline had been subletting rooms in the house, and the building’s landlord decided either to evict the tenants or raise the rent. At the time, this required permission from the Office of Price Administration, the government agency established in 1941 by executive order to control the prices of sugar, gasoline, coffee, meats, rent and other commodities.

Arline’s complaint is a goldmine of information. She states her address, when she moved in, the amount of rent paid and number of occupants. Evidently, the landlord was denied permission to evict the Browns and instead tried to raise the rent to $35 per month, prompting Arline’s appeal to the local housing authority.

In many family history investigations, solving one puzzle leads you to another question. The 1940 census revealed clues prompting me to further research, which helped me unlock my family history mystery. I now know my mother did indeed live with her family in the beautiful old Victorian at 1315 N. Broadway during the 1940s, just as she remembered, and I have a pretty good idea how my savvy grandparents afforded the rent for the entire downstairs of the big house. Grandma and Grandpa, working-class renters, took a lesson from their own lives and become landlords themselves, making getting by a little easier in wartime California.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.