Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Hands down, the most-common problem I’ve heard from genealogists throughout the years is “I can’t find my ancestor in the census.”

Though censuses might have simply missed a family, we can often find ancestors “hiding” in the census by using alternate search strategies. But when we do find our ancestors in censuses, should we assume all the information recorded there is true?

Experienced researchers know the answer to that question is no. One census record (indeed, one source of any kind) can, at most, be considered evidence. Without corroborating information in it with other sources, we can’t know a census’ accuracy.

Federal censuses are so common that we sometimes take them for granted. But no researcher is immune from being fooled into thinking they’re inherently correct. And census records are plagued by problems that bedevil even seasoned genealogists.

Read on for some of the most-pernicious ways that censuses can fool us—and how you can overcome them.

Error-Prone Details in Census Records

Population, non-population and state census records contain a rich variety of details about our ancestors’ lives. For many of us, census records form the foundation of genealogical research. And because the federal census is frequently the first source we find, it often serves as a door to the future wonders we uncover about our family.

From literacy and infrastructure to socioeconomic factors and migration, several overlapping factors impact the accuracy of information in the census. The source of the information (which, before the 1940 census, wasn’t noted by the enumerator) also affects our analysis of its reliability.

Because census records are so foundational, any inaccuracies they contain can have an outsized impact on our research. Here are three categories of census information that deserve special scrutiny—plus our own biases that we bring into research.

Ages

You’ve likely noticed that some ancestors didn’t age exactly 10 years between the decennial enumerations. An ancestor that’s 24 in the 1900 census (birth year, c. 1876), for example, might be 36 in the 1910 census (birth year, c. 1874).

This is partially because earlier generations (especially those in an agriculturally-based society) didn’t need to know their exact birthdate. Only in 1935, with the advent of the Social Security program, did that level of detail become relevant. Respondents may have also had reason to fib about age—for example, to avoid military service or to appear older or younger than their spouses.

You should always correlate the ages (and implied birth years) found in census records with more-reliable sources for age, such as birth certificates or military, court or Bible records.

Names

Census enumerators often spelled names phonetically. I’ve been genuinely surprised at creative spelling variations: for example, Watuz for the surname Waters. These variations can cause us to entirely miss ancestors, especially given our increasing reliance on keyword-searching to find records.

To help remedy this, review the actual census images in the neighborhood where you expect to find your ancestor. I’ve lost count of how many “missing” ancestors I have found this way.

Additionally, create a list of all the spelling variations you find in censuses to help you search for the same variations in other source types.

Relationships

As the meat and bones of genealogy, family relationships should be correct lest we attach ourselves to families we aren’t related to. Beginning in 1880, censuses recorded the relationship of everyone to the head of the household. Like all the information we find in censuses, we should verify those relationships using other reliable sources such as probate, court, tax and deed records. Spending more time analyzing information as opposed to searching is key.

Your own assumptions

In addition to the common errors within records themselves, we also bring our own assumptions. Subconsciously, these shape our interpretation of the information we find, creating a perfect stew of costly mistakes.

For example, if we expect all parents to be married at least 10 months before the birth of their child, we may miss valuable evidence to the contrary. (Isn’t it great to know how human our ancestors are? The foibles and flaws that vex us today also affected them.)

Other common assumptions that can create confusion include that children automatically took the surname of their birth father, that all children survived to adulthood and that people stayed in the locale of their birth for their whole lives.

4 Ways the Census Can Fool Us

Here are some specific pitfalls of using census records, with examples I’ve encountered in my own research.

1. Relatives recorded as boarders, roomers or lodgers

Beginning in the 1880 census, people could be recorded as a boarder, roomer or lodger in addition to familial relationships. However, some individuals labeled as such were actually biological relatives. With this in mind, you should always thoroughly research anyone recorded in the census to uncover possible familial relationships.

For instance, Lydia Cottman’s household in the 1900 census of Somerset County, Maryland, includes three young men named (John) Cranston, James and George Waters. All three are inaccurately recorded as boarders. But other sources revealed these men were actually Lydia’s sons from her prior marriage to a man named Daniel Waters.

2. Divorcees recorded as widows

In the past, divorce was socially stigmatized. Nevertheless, when I first began my research, I was surprised by just how many divorces occurred. People divorced for many of the same reasons they do today: desertion, infidelity and (in some cases) abuse and violence.

Many people understandably did not want divorce recorded as their marital status in the census. Instead, many simply told the enumerator they were widowed. Single unmarried women with children sometimes claimed widowhood. Even some men did the same.

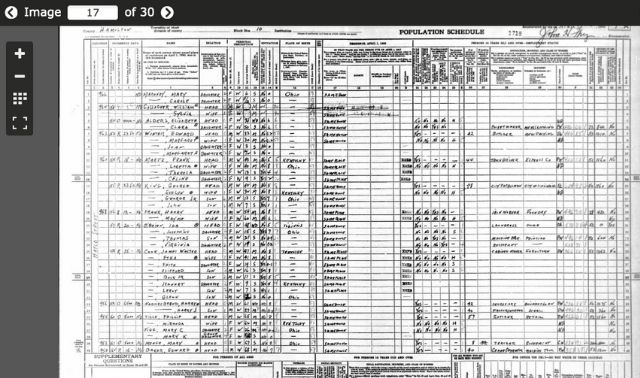

My ancestor Hannah (Barnes) Harbour was enumerated with her husband, Joseph Harbour, in the 1880 census in Hardin County, Tennessee. By 1900, Hannah headed a household of five children and was categorized as a widow (circled in red below). I was a new researcher and couldn’t locate Joseph in the 1900 census, so I believed Hannah was in fact a widow.

Local circuit court minutes revealed the true and tumultuous story. Still married to Hannah, Joseph was charged in 1883 with committing “lewdness” with a woman named Rachel Shannon. He eventually divorced Hannah and married Rachel in 1884.

The next year, Rachel also filed for divorce. Joseph and Rachel’s divorce was messy and chaotic, filled with accusations of infidelity, abuse and neglect. Joseph even noted that the child born during their marriage was not his. (Reality TV today has nothing on our ancestors!)

Last documented in county records in 1898, Joseph Harbour may indeed have died before 1900. However, he did not make Hannah a widow when he did.

3. Assuming the wife is the mother of all the children

This is another example of how assumptions hurt our research. It’s almost second nature to attribute all the children in a census family to the woman listed as the head of household’s wife (assuming she’s old enough to have birthed them).

But if we’re careful about studying the census columns that record marriage and birth information, we may be able to discern that not all are her biological children. Questions vary by census, but look for columns that report on how many children were birthed and how many are living (in the 1900 and 1910 censuses), in addition to columns that calculate marriage year. Compare between mother and supposed children, and correlate with other sources, such as marriage records, birth certificates, family Bibles or Social Security applications.

My ancestor J.M. (James) Holt appeared in 1900 in Obion County, Tennessee, with wife “Alora” (Elnora). The household includes five children, aged 13 years to 10 months. Other columns reported the couple as having been married 17 years, Elnora as having given birth to five children (five of whom were living).

Nothing could have been further from the truth. Records show that the couple actually married on 26 October 1895, less than five years prior to the census. Only the 10-month-old infant was Elnora’s biological child; the older four were James’ children with his first wife, Mintha Barnes. Only by thoroughly researching the lives of James, both of his wives and all the Holt children in sources such as vital records, deeds, military records and newspaper articles did I reveal the inaccuracy of this single census.

4. Inconsistent use of first names, middle names, nicknames and initials

Almost every genealogist encounters this at some point. In addition to phonetic spellings and transcription errors, the census can list people by a variety of names, complicating our task of proving identity.

To determine if different names in censuses refer to one person or multiple people, lean into the subject’s relationships with others: spouses, parent-children, siblings and so on. Then use probate, deed and death or burial records (and details like landownership or literacy) to verify accuracy. You can also make a timeline to determine whether multiple censuses could plausibly describe one person.

You can also research possible nicknames. “Bill” is a well-known nickname for William. But would you think to look for a Margaret as “Daisy” or “Peggy”? Family Tree’s guide to female nicknames and websites such as Cyndi’s List and FamilySearch are good sources to find possible nicknames.

In other cases, a person’s given name was just too much of a mouthful. In his 1917 WWI draft registration, my ancestor Phlenarie Holt found that name too complicated and decided to go by Flynn instead.

Middle names can help untangle a person’s name—or complicate them further. One of my ancestors was called “Leanna Moccaby” in the 1870 census, “Harriet L. Mockaby” in 1900, “Leanna McAbee” in the family Bible and “H. Leannah McAbee” on her headstone.

Be vigilant about documenting middle names and initials when they appear. Censuses, headstones and death certificates might include a middle initial or entire middle name. Military draft registrations often included middle names for men, and Social Security applications requested middle names.

People in certain occupations (such as ministers) were frequently referred to by their initials. Research censuses and newspapers using those initials, as the earlier example with minister J.M. Holt illustrated.

There’s no shortage of reasons a census might be incorrect. A census enumerator may have been too tired to return to a home and decided to ask a neighbor for the information. Or perhaps an enumerator made errors when copying information or misheard the pronunciation of a name.

But respondents may have also had reason to lie. Embarrassment may have caused an ancestor to provide false information about marriages or children. And people who could pass for “white” could migrate to another locale and assume that racial category to claim expanded privileges.

Develop a skeptic’s eye, and never take any single source at face value. Even the tried-and-true census can send us on a wild goose chase up the wrong family tree. Being aware of common census traps can strengthen our skills and help us accurately reconstruct our families.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the September/October 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine.