To access your ancestors’ vital records, probate files, deeds and other important county-level documents, most genealogy books will tell you to “go to the courthouse.” But what if the courthouse is 400 or 800 or 1,600 miles away?

Don’t panic! You can reach these valuable records without trekking across the country. Even long-distance, you can get copies from your ancestors’ courthouse. And if you strike out there, you can explore several alternative methods for getting such information.

So unpack those bags, and find out how to uncover family history clues in the courthouse without actually going there.

Who has the records?

Genealogists flock to courthouses because so much of the important paperwork about our ancestors winds up there. (In a few states, these records are kept at the town level; for simplicity, we’ll use courthouse for any repository that holds them.) Here’s a look at the family history clues courthouses hold:

Vital records: Birth, marriage and death records often contain the keys to unpuzzling a pedigree, just remember that many states didn’t begin keeping these records until the late 1800s or early 1900s. The New England states, however, kept vital records almost from their beginnings. And some large cities kept vital records before the states required them. When governments first mandated vital records, they usually stored them at the county level (at the town level in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Rhode Island and Vermont). Later, registration shifted to the state level, although some records remain on the county level, as well.

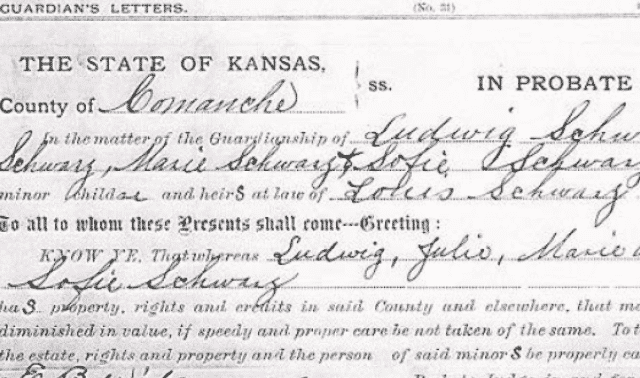

Probate files: Your ancestors’ estate files could contain a wealth of information — not only wills (some don’t contain wills at all), but also settlement papers, inventories, receipts and other records. These papers can provide clues to relationships, residences, dates of death and more. They’re typically kept at the county courthouse, but location may vary (for example, in Connecticut, they’re held in probate districts, and in Rhode Island at the town level).

Deeds: These invaluable resources record transfer of ownership and will give you the name, marital status and address of the seller; the buyer’s name and address; and the price and description of the property. Generally, people acquired land in the United States and its parent Colonies in one of three ways:

- original purchase or grant from the colony, state, territory or federal government

- purchase from a private entity

- inheritance

If your ancestor obtained land from the state or federal government, the record is at the state or federal level. E. Wade Hone’s Land & Property Research in the United States (Ancestry) explains how to research these records. After the original purchase, transfers by deed are usually registered at the county level, except in Connecticut, Rhode Island and Vermont, where they’re registered at the town level. Probate files document transfers by inheritance.

Government Agencies with Online Databases

Some of the most important genealogical documents are kept at the county level. But you don’t have to trek to your ancestors’ old stomping grounds to find them. Now, you can access many of these records without leaving home — thanks to government agencies creating online databases of their holdings. Here’s a look at two agencies in your ancestral county that are keeping up with the information age.

Clerk of courts

The clerk of courts, or county clerk, holds court-proceedings records (appeals, affidavits, indictments), residential records (changes of address, leases, mortgage deeds) and other personal records (name changes, wills, military discharge papers, vital records).

Many clerks of courts have online databases of these records, so you can search for your ancestors’ documents and then order copies. Keep in mind that these databases are new, so some agencies have indexed decades-old records, while others have indexed only recent records, or none at all. But be patient; these projects are ongoing.

To find a clerk of courts’ Web site, type the county name, followed by clerk of courts, into a search engine such as Google. For example, if you wanted to find the Hillsborough County (Fla.) Clerk of Courts site, you’d type in Hillsborough County Clerk of Courts (try putting quotes around the terms — for example, “clerk of courts” — to search for an exact phrase).

From the clerk of courts’ home page, look for a text or graphical link that refers to public records or online records. A disclaimer usually precedes the actual online database, stating that the search is intended for informational purposes only (as opposed to using the records for legal action). Just click OK or I Agree to go to the database.

You can search the database by party name (individual or business), and on some sites, you can limit your search by date or document-type code (there should be a list of codes, such as MAR for marriage records). Search results vary by county. Sometimes, you can view the full record online, either in a text format or as a scanned image. Other agencies provide only a brief description of the record and its location. But once you find your ancestors’ documents, you can order copies for a few dollars (the price goes up with the number of pages).

County property appraiser

If you know your ancestors’ address and want to find out who currently lives there, when the house was built and the current property value, look for your ancestral county’s property appraiser’s Web site. Just type the county name, followed by property appraiser (or tax assessor or auditor), into Google or another search engine.

When you find the site for your ancestral county, look for terms such as appraisal roll, property research or real estate to link to a public database of properties. Then, you can search by owner or street address to find a general property assessment, tax information and sales records, detailing when the house was sold and for how much.

As with clerk of courts records, available information varies by county. But you might be lucky enough to find a map and a detailed property description, listing the number of bedrooms and bathrooms, and even building materials, in your ancestors’ house.

This information was written by Chad Neuman and appeared in the October 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Requesting copies of records

Often, the easiest way to get copies of records is by writing and requesting them from the courthouse. First, do some preliminary genealogical research, so you can help courthouse personnel identify the correct record (You’ll waste time if you request records that don’t exist, or contact the wrong place.) Your ancestral county also may have an official Web site with information about records and cost of copies. See if the USGenWeb site for that county links to the official government site, or use a search engine to find it.

When writing to a courthouse, remember:

- First impressions count.

- Be sure your letters are legible; print carefully or type them.

- Include full contact information: postal address, e-mail address and phone number.

- Send letters to the correct office. The books listed on page 26 will help you figure out how to address your letters.

- State what record you’re looking for; provide fill I names of ancestors and relevant dates. You might need to provide female ancestors’ maiden names.

- Keep letters short. Your ancestor’s story may be fascinating, but busy courthouse employees can’t spend hours wading through several pages trying to figure our what you want. Ask about fees for records.

- Enclose a self-addressed envelope.

- Include only one or two requests in each letter. Courthouse personnel will respond most quickly to the letters that are easiest to answer. If a letter requests six records — two death records, two marriage records and two birth records, say — and the records are on different floors, it may come to the top of the pile and then go back to the bottom again.

Requesting records by phone isn’t a good idea because many letters of the alphabet sound alike over the phone. You may get a response that no record was found for your ancestor Jacob Sitler, when you’d carefully spelled out Jacob Fitler — bur when you said F, they heard S.

Vital records requests

When requesting vital records by mail, state that you’d like the documents for genealogical research. Give your relationship to the subject (s) of the record and provide this additional information if you know it:

- Birth records: full name of the person (woman’s maiden name); sex and race; date and place of birth; names of parents

- Marriage records; full names and ages of the couple; date and place of marriage; names of parents

- Death records: full name of the person; sex and race; date and place of death; names of parents

If you’re requesting the document in hopes of finding some of this information, explain this in your letter.

Probate records requests

When writing about probate files, give the full name and date and place of death — and make sure to state that you want copies of all papers related to your ancestor’s estate. Don’t say, “Just copy the important papers.” Courthouse personnel don’t have rime to read through the documents to decide what’s important, and they might not recognize the document you need to solve a pedigree problem.

Ask about the cost of copies in advance. Costs for probate files vary widely. While some agencies charge a small, per-page fee for copying, others charge a relatively high fee to check the index for estate files. Even if the fee per page is low, some estate files comprise many pages.

If your ancestor’s land belonged to different counties at different times, check with each county. In some cases, they all might have files relating to the estate.

Deed records requests

Requesting deeds is more complicated than requesting vital records or probate files. While most people have only one birth or death record, at most a few marriage records, and one probate file, your ancestor might have a large number of land transactions scattered across the state, or even across the country.

Begin by writing to the registrar of deeds in the county where your ancestor lived. If your ancestor lived there before the current county was formed, also write to the registrar of deeds in the parent county (and that county’s parent county, and so forth) to investigate earlier records.

Ask the registrar of deeds to photocopy the pages from the grantor {seller} and grantee (buyer) indexes for your ancestor’s name for a 100-year period starting when your ancestor turned 18. Sales after his death might be registered under his name (as “estate of lancestor]”) if land was sold in settling his estate or if land he bequeathed to an heir was sold later.

Your request to the registrar of deeds may yield one of four possible responses: no entries for your ancestor; a few entries; many entries for the name (possibly including other people with the same name); or the courthouse won’t research deeds by mail (most supply a list of researchers in the area).

If you don’t find land records for your ancestor — but you know he had land — he might have acquired the land in two other ways: inheritance or original grant or purchase from a government.

If your ancestor has only a few listings, order copies of the deeds. If the indexes list many deeds for your ancestor’s name, look for clues to identify your ancestor’s deeds — for example, the other person in the transaction is a known relative or associate. You can request these deeds; however, the methods in the next section may be more efficient.

When the records arrive, match up purchase and sale deeds. Are there purchase deeds for land that has no sale deeds? If so, did the ancestor bequeath the land to someone? If not, the land might have been sold as part of a bankruptcy proceeding and registered in a different set of books, or the sheriff might be listed as the grantor. The sale also might be indexed under the name of the administrator of your ancestor’s estate. If you have a sale deed with no matching purchase deed, is there a chain of title that gives clues as to how your ancestor acquired the land? Investigate the records the chain of title suggests.

For more on land records, see Locating Your Roots by Patricia Law Hatcher (Betterway Books).

Other ways to obtain courthouse records

You may have trouble getting copies of records directly from the agency that holds them. Since Sept. 11, 2001, many localities lave restricted release of vital records. Some counties will photocopy records if you give them a citation, but they won’t check Indexes. You also might find the cost of a search to be prohibitive. A thick probate file means a huge photocopying cost. Or perhaps you’re researching all the members of a large family, and you need so many records that you can’t afford to order them all.

Although some genealogical records are available only from courthouses, many have been transcribed and published in several formats:

- books and magazine articles

- microfilm or microfiche versions of books, periodicals or actual records

- transcriptions, abstracts or scans of records on CD-ROM or the internet

All these formats convey the same information. Here’s how to find out if records you’re seeking are available in these formats — and if so, how to get them:

Books

Many transcriptions or abstracts of courthouse records are published as books or as articles in genealogy journals. And usually, these books and journals include the information you need to order copies of the records. You can find books of transcriptions or abstracts by searching the catalogs of libraries with large genealogy collections; most of these catalogs are now searchable online (see next page). For catalogs that use Library of Congress subject headings, as most do, look for subject headings such as these (substitute your state and county of interest):

- Armstrong County (Pa.) — Genealogy

- Wills — Pennsylvania — Northampton County

- Deeds — Pennsylvania — Butler County

- Probate Records — -Illinois — Morgan County

- Marriage Records — Tennessee — Carter County

- Registers of Births, etc. — Ohio — Muskingum County (this subject heading includes births, deaths and vital records)

Once you’ve identified books of records from your ancestral area, find out if they’re still available from the publisher, or on interlibrary loan. If you find a book that might have information about your family but isn’t available on interlibrary loan, ask your librarian to request photocopies of the table of contents and the index pages that list your ancestors. From these pages, you might identify other pages that will help your research, and then you can request more copies.

You may also belong to a genealogical society that can help. For example, the New England Historic Genealogical Society (NEHGS) loans some of its books to members for a small fee.

Magazines

You can tap several indexes to genealogy-magazine articles. The most easily accessible is the Periodical Source Index (PERSI). Created by the Allen County Public Library (ACPL) in Fort Wayne, Ind., PERSI indexes genealogy and local history periodicals written in English and French since 1800. This resource began as a print publication, but it’s now available as an online subscription database through Ancestry.com. Your local library also might have access to PERSI. Use one of the locality search options to look up your ancestor’s county, and choose vital records, probate records or deeds as the record type.

Check an online catalog to find out what record books are available on interlibrary loan.

You can order copies of articles indexed in PERSI from the Allen County Public Library (ACPL, 900 Webster St., Box 2270, Fort Wayne, IN 46801, 219-421-1200). Contact the library or visit the ACPL website for current fees. Also check to see if your local library can get the material for free or for a smaller fee. Some magazines have been digitized by the society that published them.

Transcriptions

Many transcribed records are available on CD-ROM. You can find them by checking the Web sites or catalogs of the major genealogy CD-ROM publishers. Just be sure to investigate the contents before buying, as some titles suggest broader coverage than the CDs actually have. You may also be to view transcribed records online.

Online options

Because of privacy considerations, many viral records will never be available on the Internet. But many primary sources are available online. These sites can help you find courthouse records:

Cyndi’s List includes headings for Births & Baptisms, Death Records, Marriages, Wills & Probate, and US — Vital Records. Click on the United States Index, and you’ll find links to state and county sites.

USGenWeb aims to provide Web sites for genealogical research in every US county. Surf the USGenWeb site — which is organized by state — to find a link to your ancestral coounty’s site; it might include transcribed or scanned records.

Be sure to check the websites of historical or genealogical societies for the area where your ancestor lived. For example, the New England Historic Genealogical Society has posted transcriptions of Massachusetts vital records. You have to be a member to view them, but membership may be cheaper than visiting the area in person.

You also can use a search engine such as Google to find sites relating to your ancestor’s county. To help weed out false hits, include the state name in your search.

Ancestry and other commercial sites also offer scans, abstracts or transcriptions of courthouse records. You’ll need to subscribe to view these, but you can do the first step for free: Search for an ancestor’s name and dates, or a surname, and see what turns up in the database. This will help you decide whether it’s worthwhile to buy a subscription.

After some research, you may be curious enough to visit your ancestral home — to see what it looks like and to do research there. Or you might hire a professional genealogist who’s familiar with sources in the area and can do more thorough research than you can from a distance. Using a combination of strategies and resources, you can obtain many of the documents created by or about your ancestor. They’re all waiting for you to find them — in the courthouse.

A version of this article appeared in the June 2003 issue of Family Tree Magazine.