Editors’ note: Article written by Rick Crume, unless otherwise noted

Pictures of immigrants passing through Ellis Island, lugging all their worldly possessions toward the promise of a better life, are iconic images of American history. A 27.5-acre island off the tip of Manhattan, Ellis Island was the entry point for 71 percent of US immigrants between 1892 and 1924. Almost half of Americans have someone on their family tree who arrived there.

Shipping companies kept detailed passenger lists, called “manifests.” Before the Ellis Island passenger lists were indexed, finding your ancestor on a microfilmed manifest was nearly impossible if you didn’t know the ship’s name or approximate arrival date.

EllisIsland.org

Launched in 2001, the Statue of Liberty―Ellis Island Foundation website now has a searchable database with 65 million records of passengers and crew who entered the Port of New York from 1820 to 1957. Volunteers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints transcribed microfilmed lists to create the original online index; names in the database link to images of the passenger lists on which they appear. You can search the database and view the lists for free, and purchase immigrant certificates, copies of passenger manifests and photos of ships.

The US federal government started requiring ship captains to submit lists of passengers to customs officials in 1820. Three immigrant processing facilities served New York City: Castle Garden (1855-1890), the Barge Office (1890-1892) and Ellis Island (1892-1954). EllisIsland.org has passenger lists from all three centers and the records continue up to 1957 with lists of airline passengers.

Early passenger lists were recorded on a single page and included full name, age, gender, occupation, nationality, destination (country), the ship’s name and date of arrival. By 1907, the lists expanded to two pages with 29 columns and information on birthplace, marital status, last permanent residence and physical description.

Even if your immigrant ancestors arrived before 1820, you might still find relatives at EllisIsland.org. The indexed passengers include ships’ crewmembers and US citizens returning from abroad. Our guide will help you find your ancestors who stepped foot onto Ellis Island.

Getting started on EllisIsland.org

You’ll need to register for free to view search results on EllisIsland.org and to take advantage of options such as saving searches and annotating records. Click on the icon that looks like a person in a circle at the top right to create an account or to log in with your email and password. Hover your mouse over the Discover tab and select “Search Passenger and Ship Records” or click on “Passenger search” at the upper right. Then click on “Start Your Search” to open the Passenger Search form.

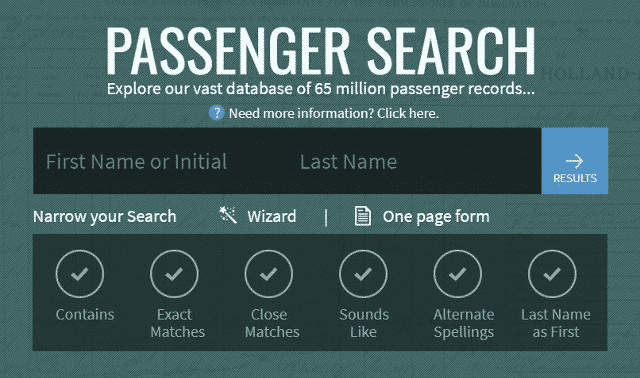

Passenger search

The basic search form has spaces for first name or initial and last name. If you enter just an initial in the first box, matches will include names with just the initial and first names that start with that letter. Click on Exact Matches to narrow your search or on other options to expand your search to include similar names.

Click on the Wizard to add other search criteria, such as date of arrival, town of origin, place of birth, port of departure and ship name. Use the right and left arrows to page through the options. Or click on “One page form” to see all the search options on one page. All fields except last name are optional. Then click on Results to do the search. If you get too many matches or too few, click on Filter to modify how closely the names must match.

Almost all the records in the database include at least a last name and a year of arrival, if these details were legible on the original list, but the other fields may have been left blank. If you choose a term in a field such as ethnicity or town of origin, you won’t get matches on passengers for whom that field is empty. So if you get too few matches, search on fewer fields.

The Sorting Options let you sort the results by first name, last name or arrival date, in ascending or descending order. Under Select View, you can opt to display the search results in tiles or list view. Hover your mouse cursor over the ‘i’’ beside a name to view more information on the passenger. Click on icons in the Action column to display the passenger record, the ship image (if available) and the ship manifest (passenger list).

Other resources on EllisIsland.org

Explore these links at the top of the passenger search page.

Ship Search lets you search the passenger lists by ship name and date of arrival. That could be useful if you can’t find someone using Passenger Search, but you know at least the approximate date of the ship’s arrival and maybe even its name. However, I found that results on this search don’t always link to the right passenger lists.

Family History features several stories that exemplify the diversity of American families.

Oral Histories lets you listen to interviews with nearly 2,000 passengers and their families, immigration officials, military personnel, detainees and Ellis Island employees. You can search these firsthand accounts of the immigrant experience by name, country and topic.

Honor Your Family lets you commemorate an immigrant or another loved one by having his or her name inscribed on the American Immigrant Wall of Honor located at the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration. For a fee, starting at $150, you also receive a certificate honoring the immigrant. Funds from the project are used to restore and preserve the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Wall of Honor lets you search names already inscribed on the wall.

Flag of Faces is an interactive mosaic of pictures exemplifying human diversity on display in the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration. You can search the photos by the names of people pictured and the photos’ donors.

EllisIsland.org search tips

Many passenger lists, whether handwritten or typewritten, are hard to read. It’s safe to assume that a large percentage of names and other information from these records was transcribed wrong in the passenger lists on all five websites. If you can’t find a passenger, try all the search options for names, such as “Sounds Like” and “Alternate Spellings.”

- Neither the basic nor the advanced search supports wildcards, but you don’t need to spell out the whole first name. The basic search finds first names that begin with what you enter in the box: Search on Joh and matches include Joh., Johann and John.

- Names were transcribed as they appear on the original passenger list, even if they were abbreviated. So search on Chas for Charles, Eliz for Elizabeth, Geo for George, Jas for James, Jno for John, Joh for Johan or Johann, Jos for Joseph, Patk for Patrick, Thos for Thomas and Wm for William. Also, try nicknames such as Ed, Tom and Will and foreign versions of names (for example, Pierre or Pietro for Peter).

- If a last name may be more than one word, search with and without the space, as in Dewitt and De Witt.

- Year of arrival and age at arrival might not match your information from other sources. Search both fields on a range of at least three to five years.

- Many passenger list forms, especially more recent ones, have two pages. Use the ‘previous’ and ‘next’ buttons to make sure you don’t miss any pages pertaining to a particular list.

- Search these passenger lists not only for immigrant ancestors, but also for relatives who may have traveled or lived abroad and came to the United States through the port of New York.

- For clues to when your immigrant ancestors arrived, look for them in the US federal censuses of 1900, 1910, 1920 and 1930. They list each immigrant’s year of arrival.

- The port of departure recorded on a passenger list might not be the port where all the passengers began their journey. It’s often the most recent port where the ship was located before arriving in New York. So a passenger who emigrated from Germany could appear on a passenger list for a ship whose port of departure was Liverpool, England.

Other websites with Ellis Island records

These five websites have the same collection of passenger lists. Note that the New York passenger lists on FamilySearch are divided between three separate record collections. On Findmypast, they’re part of a larger record collection that includes other US passenger and crew lists.

| Website | Record Collection |

|---|---|

| Ancestry.com | New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957 |

| Ellis Island (free) | Passenger Search |

| FamilySearch (free) | New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1920 New York, Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1925 New York, New York Passenger and Crew Lists, 1909, 1925-1958 |

| Findmypast | United States, Passenger and Crew Lists To narrow your search to New York passenger arrivals, select New York and NY as the arrival state. |

| MyHeritage | Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 |

Comparing Ellis Island records search results

You might expect to get roughly the same results when searching any of them. In order to see how they compare, I searched each site for the exact spelling of my last name Crume. The results were surprising.

As the chart below shows, a search on the exact spelling of the surname Crume produces 45 matches on EllisIsland.org, 50 on Findmypast, 53 each on both FamilySearch and MyHeritage, and 60 on Ancestry.com. So, did those other sites find passengers that EllisIsland.org missed? Indeed, each of those sites apparently turned up some matches missing on EllisIsland.org: eight each on FamilySearch and MyHeritage, 10 on Findmypast and 24 on Ancestry.com. But EllisIsland.org also found five matches not on Findmypast and nine missing from Ancestry.com. In fact, all of these sites misread some names. So, for example, several of the 60 Crume matches on Ancestry.com weren’t really Crumes.

This chart shows the results for a passenger search on the exact spelling of the last name Crume. While all of these sites have the same passenger lists, they transcribed some names differently.

Surname spelling matches: New York City Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

| EllisIsland.org | Ancestry.com | FamilySearch | Findmypast | MyHeritage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matches | 45 | 60 | 53 | 50 | 53 |

| Matches on both EllisIsland.org & this site | 36 | 45 | 40 | 45 | |

| Matches on EllisIsland.org, but not on this site | 9 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| Matches on this site, but not on EllisIsland.org | 24 | 8 | 10 | 8 |

Points to keep in mind when searching Ellis Island records online

A closer look at the divergent search results on the five websites’ New York City passenger lists highlights three important points to keep in mind when searching them.

1. If you don’t find a passenger on one of these five websites, try the others.

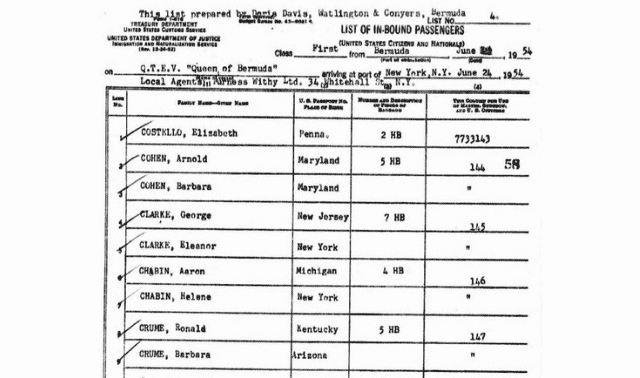

- Ancestry shows that S. Anna Crume arrived on Dec. 6, 1910, on the ship Thames, but the passenger is recorded as male. Ancestry.com, EllisIsland.org and FamilySearch all transcribed the name as S. Allan Crane, which looks more likely.

- According to Ancestry.com, passengers Bruno and Maria Crume from Bremen arrived on the ship Susquehanna on July 14, 1922. The record image shows the first 13 columns of the passenger list. Click on the right arrow and you can view columns 14 to 33 on the next image. Column 19 asks for the name of the friend or relative in the United States whom the passenger was going to join. It shows that Bruno’s brother Emil Gruhn (Maria’s brother in-law) lived in Brooklyn, New York. While Bruno’s last name isn’t clear, Emil’s is — so their last name must have been Gruhn, not Crume. The other four sites correctly indexed the name as Bruno Gruhn.

- Ancestry.com shows a Pauline Crume, a domestic servant from the city of Paris arriving on Nov. 10, 1926, on a ship named Paris. All the other sites transcribed the name as Pauline Grume. The names are in alphabetical order on this passenger list and Pauline is listed after names starting with F, so her last name was definitely Grume, not Crume.

- All the sites, except EllisIsland.org, show that my relative James Arthur Crume arrived on Feb. 19, 1945, on the ship Carl B. Eielson from Port Said, Egypt. The name is printed very clearly on the passenger list. The name must have been transcribed wrong or missed altogether on EllisIsland.org.

- All the sites, except EllisIsland.org, show that Rita Crume arrived in 1948 on a ship named Ancon from Panama. The name is typewritten and clearly legible.

2. Take a close look at the image of the original passenger list to see if all the information was transcribed correctly and to look for additional clues.

- Among the Crume matches on FamilySearch, Findmypast and MyHeritage is the name Masscias Crume. Actually, he’s not listed as a passenger, but as the father of passengers Rosa and Angela Krume of Wien (Vienna), Austria, who arrived on Nov. 28, 1907, on the ship Amerika. (This passenger list asks for “the name and complete address of nearest relative or friend in country whence alien came.” All three of these sites index the names of those friends and relatives.) These sites transcribed Rosa and Angela’s last name as Krumd, but it looks like Krume to me, and their father’s name as Masscias Crume, but I think it looks like Matthias Crume. Apart from errors in transcription, the original record seems to have spelled the same last name two different ways (Crume and Krume).

- Ancestry.com shows that a passenger named Alice Crume arrived from England on May 14, 1926, on the ship Mauretania. That passenger list has a column for name of the passenger’s closest friend or relative in his or her home country and Alice’s was her “Mother Mrs S Crump” back in Staffordshire, England. While the last letter of Alice’s surname is hard to read, her mother’s name is clear, so Alice’s name must have been Crump, not Crume. The other four sites correctly indexed the name as Alice Crump.

3. Take advantage of each website’s unique features.

- While these five websites have similar search options, there are differences. For example, only Ancestry.com and EllisIsland.org let you search on a passenger’s exact date of arrival.

- If you can’t find someone using Passenger Search, but you know at least the approximate date of the ship’s arrival, it might be worthwhile to browse the original passenger lists. All of them, except EllisIsland.org, let you browse the lists by date.

- EllisIsland.org’s basic search form requires you to enter at least a last name, but you can search without a last name on the other four sites. If a search on first and last names together fails, try searching on just a first name or a last name in combination with other information, such as date of arrival, ship and town, region or country of origin.

- There is a way to search EllisIsland.org without a last name. Using either the Wizard or the one-page form, enter the number ‘0’ in the Passenger ID field. Then enter information in the other fields, including, optionally, the first name field. To cover all passengers in the database, also try the same search with a ‘1’ in the Passenger ID field. This strategy works because every passenger in the database has an ID number containing ‘0’ or ‘1.’

- Usually, if you right-click on an image on the web, you get an option to save the image, but that function is disabled on EllisIsland.org.

Rick Crume

Ellis Island records on microfilm

Castle Garden customs lists (1820–1891)

Prior to the mid-19th century, the United States had no immigrant inspection stations. Then in 1855, Castle Garden (now known as Castle Clinton National Monument) opened on the southern tip of Manhattan. Here, short inspections and medical examinations of arriving passengers took place. Castle Garden gave way to Ellis Island in 1892. Passenger lists from 1820 to about 1891 were known as customs lists. They were usually printed in the United States, completed by ship company personnel at the port of departure, and maintained primarily for statistical purposes. So they contain only bare-bones information: the name of the ship and its master, the port of embarkation and the date and port of arrival, plus each passenger’s name, sex, age, occupation and nationality.

These lists (with some gaps) have been microfilmed and are available through the National Archives (NARA), and through FamilySearch and its local centers. Generally speaking, NARA’s regional records services facilities have films for the ports in their jurisdiction. The guide Immigrant & Passenger Arrivals: A Select Catalog of National Archives Microfilm Publications, Revised details more fully the availability of records and indexes for each port, or you should be able to locate a copy at most genealogical libraries.

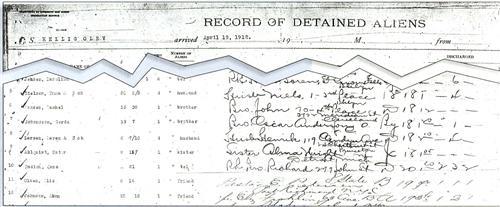

Records of Detained Aliens (1903 and forward)

Beginning about 1903, the passenger arrival lists began to include a supplemental section for detainees. Many immigrants were detained for short periods of time at the port of arrival until relatives came to claim them; this was particularly true of unescorted women, whether or not children accompanied them.

Detainee lists, or Records of Detained Aliens, that have survived were microfilmed with their corresponding passenger lists at the end of the lists of arrivals. They contain each detainee’s name, the cause for detention and the date and time of discharge. The number of meals the detainee was fed during detention was also recorded. If the emigre was deported before being released from the immigrant receiving station, these records stated the reason and the deportation date. The abbreviation LPC meant “likely public charge” (that is, likely to wind up on the public dole), and LCD signified “loathsome contagious disease,” two main causes for deportation.

Check subsequent passenger lists and indexes for aliens who were deported — they might have entered the country later when they were able to pass inspection. Another common way for aliens to re-immigrate was to save enough money and re-enter as a first-or second-class passenger, who underwent less stringent exams aboard ship.

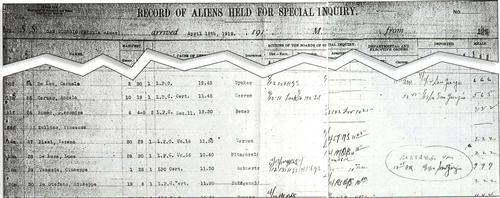

Following the Record of Detained Aliens will be a page or pages of the Record of Aliens Held for Special Inquiry. This form noted the cause of the detention or rejection, along with actions taken by the Board of Special Inquiry, the date of hearings and the number of meals eaten during detention. For deportees, you’ll find the date and the name of the vessel and port from which they returned to their native land. If a rejected immigrant was waiting for someone, the form will also include the name and address of the American contact.

Stowaways: Got a family story of Great-grandpa being a stowaway on a ship bound for Ellis Island? It would be extremely rare for an ancestor to slip by all the inspections upon arrival. Once a stowaway was discovered, his name would get recorded on the list and indexed like anyone else. Of his fate once he was discovered … ah, that’s another story. He might be deported, so check the list of those detained and those held for the Board of Special Inquiry.

Port of New York microfilmed passenger lists indexes

For the Port of New York, indexes to the microfilmed passenger lists span the years 1820 to 1846, 1897 to 1902, 1902 to 1943, and 1944 to 1948. Some of these indexes are alphabetical; others use the Soundex code, which turns each last name into a letter and numbers so that similarly spelled (and misspelled) names are filed together. In Soundex, for example, Lenin and Lennon are both L550. The alphabetical indexes may not be in strict alphabetical order, however, or may be misfiled. Here’s how the Port of New York’s indexes are supposed to be arranged:

- 1897 to 1902: Alphabetical by surname, then by given name.

- 1902 to 1943 — A through D surnames: Arranged by Soundex code, then alphabetically by the first letter or first two letters of the given name, then by date of arrival (or volume number when date is not given).

- 1902 to 1943 — D through Z surnames: Arranged by Soundex code, then alphabetically by given name, followed by those whose ages were not given (for the years 1903 to 1910), then by age at arrival.

If you don’t find your ancestor, check for him or her by initials, instead of a full given name (Patrick Murphy as P. Murphy), and check for variant spellings. As in the computerized database, women might be recorded under their maiden names, not their married surnames. The microfilmed index cards will look different, depending on the arrival year. Some cards have all the fields written out and are straightforward, giving name, age, group number, list number, sex, citizenship, steamer, line, date and port. But other cards may baffle you. Finding the name is no problem, but what are all those other numbers? The Soundex code number is always in the upper left corner.

Other information available by year: Below is a guide to the other information during different years. This pertains primarily to the cards for the Port of New York; other ports may have their own irregularities.

- Dec. 1903 to June 1910: name, group number, list number, vessel, date of arrival

- July 1910 to 1937: name, age/sex, list number, group number, volume number

- 1937 to June 1942: (top line after Soundex code) month/year; (center line) name, age/sex, list number, group number, volume number; (bottom line) vessel

- July 1942 to Dec. 1943: (top line) Soundex code, vessel or plane, date; (center line) name, age/sex, list number, group number, volume number

How to find immigrant ancestors on passenger lists microfilm

Once you’ve found a mystery immigrant in the index, copy all of the information from the index card. Next, go find the full passenger list on microfilm (or you may now know enough to find your ancestor online as well).

The arrival date is given on cards prior to June 1910, so let’s look at these first. The microfilm rolls for the passenger lists will be catalogued differently in different repositories, so check with the librarian to find the roll with the date you need. Regardless of how the films are catalogued, however, they’re all microfilmed in rough chronological order; some lists may be out of order.

You’ll typically find two to three “volumes” filmed on one microfilm roll. A title sheet precedes each volume, giving you the volume number, the arrival dates, the names of the steamships in the order they’ve been microfilmed, the ports of departure and the number of sheets in each manifest.

Location of group number on the passenger list

Once you find the ship’s list, use the other information from the index card to find the exact page. The “list number” refers to the line number on the manifest, running down the left side of the sheet. The group number is the tricky one. You’ll probably note several numbers on each passenger-list page: stamped numbers, numbers handwritten in grease pencil, numbers on the bottom of the page and numbers at the top. Once again, the placement of the group number varied by year. Here is the breakdown for the Port of New York:

- 1897 to 1902: usually top right comer

- 1902 to 1908: usually greased pencil or stamped numbers at top left

- 1908 to 1943: usually stamped numbers at bottom left

To decipher the information on the cards after 1910, on which no date appears, you’ll need to do an extra step. Consult the finding aid Immigrant and Passenger Arrivals: A Select Catalog of National Archives Microfilm Publications (see box) to find the appropriate volume number, which will list the date of arrival for that volume, along with the National Archives microfilm roll number. If you’re at the FamilySearch Library in Salt Lake City, consult the immigration finding-aid binders in the reference section of the United States/Canada floor. Look for the volume number, which gives you the date of arrival, followed by the library’s microfilm call number.

The advantage of microfilm

Anyone who’s used both microfilm and online records knows it’s far faster to crank through a roll of microfilm than it is to download computerized images of passenger lists, one page at a time. Sometimes, the lists span two pages, so it takes several minutes to view your ancestor’s full list. And some of the pages, for whatever reason, were digitized out of order. So you might land on the second page of information; then you need to figure out whether to click on Next Page or Previous Page. The images of pages that don’t include passenger information were also digitized, making it time consuming to view the whole ship’s list.

Microfilm also makes it easier to see tilings in context. Passengers traveling in first and second class were recorded in a separate section of the same list for that ship. So on microfilm, you’ll find a page or two for the first class passengers first, then a few pages for the second or saloon class, then multiple pages for the steerage or third class.

Perhaps the biggest disadvantage I’ve found in using the computerized images is that it takes forever to get to the end of that ship’s list. Why would you need to see the end? That’s where more good stuff is hiding: Look for records of aliens who were held by the Board of Special Inquiry at the end of the passenger list.

Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the December 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: May 2025