Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Q: I’m researching my great-grandfather Col. Samuel John Calhoun Dunlap, and have traced the family to the mid-1700s in the Camden, S.C., area. I’ve hit a roadblock many with family of that era face: How do I make the link back to Scotland? I understand no US passenger lists exist prior to 1820.

A: Your roadblock may not be as frustrating as you fear, although you’re correct that official passenger records weren’t kept before 1820. A number of other resources might help, such as Genealogical Publishing Co.’s Colonists from Scotland: Emigration to North America, 1707-1783 by Ian Charles Cargill Graham (originally published by Cornell University Press in 1956). You can search this book on HathiTrust.

Check WorldCat.org to find a nearby library that holds this volume, along with other potentially useful titles. Scottish Emigration to Colonial America, 1607-1785 by David Dobson, for example, might help you understand your ancestor’s passage to America.

The subscription site Ancestry.com has several databases for finding early arrivals from Scotland. Its Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s lists some 600 Scottish rebel prisoners transported to the American colonies in 1716. Among these, interestingly, is a James Dunlap, who potentially could be connected to your family. Ancestry.com also has three databases titled Original Scots Colonists, which cover 1607 to 1707, 1612 to 1783, and Caribbean colonists 1611 to 1707. In the first of these, I happened to find several Dunlops who emigrated to South Carolina. A group of some 150 Scots colonists arrived in Charleston in 1684; given that several Dunlops were among them, it’s possible your ancestors trace to this migration.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2012 Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: February 2025

Q: Where are passenger lists for ships sailing from Antwerp, Belgium? I can find the arrivals in New York, but not the corresponding departures.

A: Antwerp was an important departure port not only for emigrants from Belgium, but also for Germans headed to America. Unfortunately, only the embarkation lists for 1855 have survived; these are indexed and are available on microfilm through FamilySearch. This index covers about 5,100 emigrants, many from Germany, and lists name, age, place of origin, name of ship and place where the passport was issued. German troops destroyed the other registers in 1914, at the outbreak of World War I. The Ludwigsburg State Archives has preserved a list of emigrants on the ship Vaterlands-Liebe, leaving Antwerp for Philadelphia in May 1817, but only those from Württemberg. You may be able to find records relating to your ancestors’ departure from Antwerp in the City Archives of Antwerp, which includes hotel registers, lists of émigrés, general records on German emigrants, and passport and visa registers. Most of these records are incomplete, however, so finding your ancestors may involve some luck.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2014 Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: February 2025

Q: Are there American records on immigrants who left US ports to go back to their native countries?

A: The United States didn’t require passenger records for ships departing from American ports, only for arriving vessels. A handful of such records do exist, primarily in private hands, and the free Olive Tree Genealogy site has a special project to transcribe them all. You also can check old newspapers, which sometimes published names of outbound passengers.

Many foreign countries did maintain records of arriving passengers, much as the United States did, so you might find records of outbound Americans in the country where they landed. For example, Ancestry.com has a database of UK and Ireland Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960 from the UK National Archives; it indexes the Board of Trade’s passenger lists of ships arriving from foreign ports outside of Europe and the Mediterranean, including the United States. Another database, England, Alien Arrivals, 1810-1811, 1826-1869, lists non-British citizens arriving in England. Not all nations’ arrival records are as complete or readily accessible as the United Kingdom’s, but this is likely the best avenue to explore.

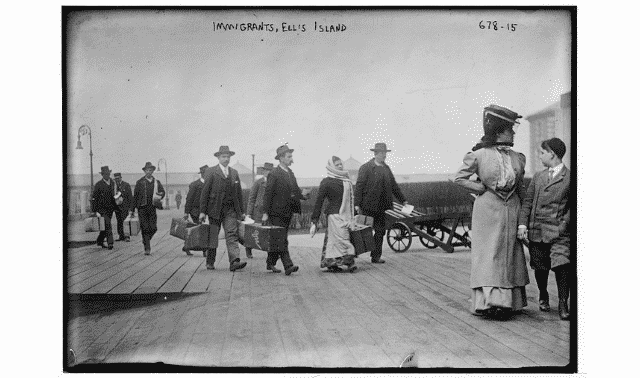

If you believe your ancestor returned to the United States after a sojourn back in the old country, keep in mind that those non-immigrant passenger list entries can be found just like any other arriving passenger records. Many of the arrivals recorded in the Ellis Island database, for instance, are for persons already living in America.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2014 Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: February 2025

Q: What’s the best place to find passenger ship crew lists? According to his naturalization certificate, my great-grandfather entered the United States at New York in January 1856. I suspect he was crew, as he lists himself as a mariner and ship’s cook.

A: An early 19th-century law required the masters of American vessels arriving at US ports from abroad, or leaving US ports on foreign voyages, to file crew lists with the customs agent at the port of entry. The original purpose of the act was to protect American mariners against the threat of impressment, by providing a convenient means of identification. But the crew lists often included both Americans and foreign-born sailors. The National Archives and Records Administration has 19th- and 20th-century crew lists on microfilm. The microfilmed records constitute the only existing copies of these records, as the originals were destroyed after the Immigration and Naturalization Service microfilmed them in the 1950s. Find descriptions of many of these holdings by searching on crew lists in the Archival Research Catalog. Some of these records have been digitized online and the FamilySearch Wiki provides links to online collections.

It’s possible your ancestor arrived aboard a foreign vessel. Non-US vessels were exempt from the law until the passage of the Immigration Act of 1917, which required all alien seamen on vessels entering the country to be documented. The National Archives has an “Index to Alien Crewmen Who Were Discharged or Who Deserted at New York, New York,” but unfortunately it covers only 1917 to 1957. It is available on FamilySearch. Whether crew or not, if your ancestor got off the ship and entered the United States, he should be listed in immigration records such as those at Castle Garden, which hosts 11 million transcribed records from 1820 through 1892.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the December 2010 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: February 2025

Q: I can’t find a passenger list for the 1738 voyage of the Princess Augusta, which sailed from Rotterdam, Holland, and wrecked in December of that year on Block Island, R.I. What happens to passenger lists of ships that never reach their final destination?

A: Passenger lists weren’t common until after 1820, when the United States passed a law requiring them, so it’s likely one didn’t exist in the first place. After 1820, lists were created at the port of departure as passengers obtained tickets. The lists traveled with the captain to the arrival port, where immigration officials matched up names on the list with passengers coming off the boat. If the ship went under, the list probably did, too.

You may be able to learn something about who was on the Princess Augusta, though. The wreck is the basis for John Greenleaf Whittier’s poem called The Palatine (so-called because the ship carried many people from the Palatinate region), published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1867.

According to a Boston-based news site, now archived on the Wayback Machine, surviving Princess Augusta crew members testified in a deposition that during the voyage, “provisions were scarce, half the crew had died, and others were hobbled by the extreme cold.” After the ship ran aground in a snowstorm, its captain, Andrew Brook, encouraged those on board to take what they could.

The deposition was reprinted in 1939 by E.L. Freeman Co. The short book is called Depositions of officers of the Palatine ship “Princess Augusta”: wrecked on Block Island, 27th December, 1738 and which was apparently the “Palatine” of Whittier’s poem. You can find it at large libraries (try to borrow it through interlibrary loan of yours doesn’t have it).

You also may find more information in articles such as “The Emigration Season of 1738—Year of the Destroying Angels,” in The Report, A Journal of German-American History, volume 40 (1986), from the Society of the History of the Germans in Maryland.

Two legends grew out of the incident. According to one, Block Island residents nursed rescued passengers back to health; the second says islanders lured the ship onto the shoals with false lights for the purpose of pillaging it, then set it afire. Supposedly, apparitions of a burning Princess Augusta haunt the island today.

Answer provided by Allison Dolan

Last updated: February 2025