Q: Without knowing my ancestor’s hometown, I can’t seem to find information from his country of origin. How can I learn this key fact?

Q: I think I found the name of a town in Europe where my ancestor came from, but how do I find out where it was?

Q: Were sponsors required of immigrants coming to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

Q: How did sponsoring immigrants work in the 1880s?

Q: Without knowing my ancestor’s hometown, I can’t seem to find information from his country of origin. How can I learn this key fact?

A: After home sources, such as letters and family Bibles, the best place to find an immigrant’s town of origin is US naturalization records. This is especially true for later arrivals: All naturalization paperwork after 1906 lists the new citizen’s town of origin; earlier documents may or may not.

Other naturalization procedures before 1906 also lacked uniformity, reflecting the fact that any court—local, county, state or federal—could handle your citizenship paperwork.

Duplicates of records after Sept. 27, 1906, are with the US Citizenship and Immigration Services; request them using Form G-639. The agency can take a long time to respond, however, so try other sources first.

FamilySearch has microfilmed many naturalization records and indexes, which you can rent to view at your local FamilySearch Center. The catalog can tell you what records are available; you may even be able to browse them online at FamilySearch.org. Ancestry.com has a database indexing naturalization records from 15 states.

MyHeritage.com and World Vital Records have an index of 3.7 million naturalization records. The limited information in an index will likely mean a follow-up to retrieve a complete copy of your ancestor’s paperwork.

You can search digitized documents from a dozen states at Ancestry.com. Also check the regional branch of the National Archives closest to where your ancestor would’ve filed his papers.

You’ll find three types of naturalization records—declarations of intention (“first papers”), petitions for naturalization (“final papers”) and certificates of citizenship. The petitions—filed after a waiting period, typically five years—usually give the most detail. Note that women rarely applied for citizenship before 1922; until then, wives became citizens when their husbands did.

You can narrow the time period for your search using the 1920 US census, which listed citizenship status (Na for naturalized, Pa for filed first papers, Al for alien) and year of naturalization. The 1900 and 1930 censuses listed citizenship status, but not the year.

A version of this article appeared in the December 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: I think I found the name of a town in Europe where my ancestor came from, but how do I find out where it was?

A: The single most important piece of information you need to trace your family abroad (besides their names, of course) is their home village or city.

Knowing just that they hailed from Poland or Portugal—or even a province such as Saxony or Sicily—won’t get you far. Most foreign records are kept and organized at the local level, just as they are in the United States. Even the Salt Lake City-based Family History Library (FHL) catalogs its holdings by locality.

Further, national identities and borders have changed significantly over the centuries. Italy as a unified nation has existed only since 1861, and Germany since 1871. The countries your ancestors left may not even be on the map anymore—think of Austria-Hungary, Yugoslavia and the Ottoman Empire (which once encompassed much of Eastern Europe and the Middle East). But archives and their records tended to stay put. So if your “Austrian” great-grandmother’s village is in what’s now the Czech Republic, you’d have little luck trying to find her birth or death records in modern-day Austria.

The impact of those political changes can trickle all the way down to the search for your ancestors’ town. In areas where land changed hands, cities may have had multiple names reflecting the languages of the various political entities in power. For instance, Bratislava, Slovakia, originated as Pressburg; Ribeauvillé in France’s Alsace region was known as Rappoltsweiler until the 1800s. Then there are the differences in English versus native-language spellings: We know Venezia, Italy, as Venice, and København, Denmark, as Copenhagen.

For these reasons, you shouldn’t make a mad dash to the atlas when you uncover a town of origin’s name in your research. First, figure out the correct spelling of that place, whether the name has changed since your family lived there, and if the word you’re looking at is a city at all. To do that, turn to a gazetteer, a geographical dictionary, for your ancestral country. Gazetteers tell you a town’s location (so you know where to look for it on a map), alternate names and jurisdictions it belongs to (district, province, even the parish in some cases).

You can find historical gazetteers at major public libraries, as well as the FHL and its branch Family History Centers (FHCs). We like the online worldwide gazetteers listed by the New York Public Library and Falling Rain; check the listings for your ancestors’ region or try a Google search on the place plus gazetteer to find country-specific sites. Many online gazetteers even will plot towns on a map for you.

Q: My daughter-in-law’s father, born in Germany, came to the United States in 1950 aboard a ship manned by the US Navy. Why would he have immigrated this way?

A: He may have been transported under the Displaced Persons Act, passed after World War II to help deal with the crisis of displaced individuals throughout Europe. Beginning in 1948, more than 200,000 displaced persons and 17,000 orphans received visas without regard to immigration quotas. The act was amended in 1950 to add another 121,000 visas plus additional provisions for orphans, and extended in 1951. Those classified as displaced persons were mostly Eastern Europeans, often who’d been forced to work in German factories and farms; others were survivors of German concentration camps. Before being issued a visa, a person had to have an American sponsor and be screened by a board set up in Hamburg “to sift out Communists and other subversives.”

The US Navy and the Army Transport Service (later the Military Sea Transportation Service) transported many of the “DPs,” mostly from the port of Bremerhaven. Built to move nearly 3,500 GIs, a troop ship typically carried fewer than 700 refugees, according to an account at the American Merchant Marine at War site.

One crewman aboard the General M.B. Stewart recalled its arrival in New York with passengers ranging from 7 weeks to 79 years old: “As the ship approached the Statue of Liberty, the fireboats sent up their streams of water and the whistles of greeting reached a crescendo. New York was welcoming these citizens-to-be as only New York can welcome … Amidships were 11 foreign flags representing the nations from which these future citizens had been drawn.”

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2015 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

Q: Were sponsors required of immigrants coming to America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries?

A: Sponsorship in US immigration has a complex history. Today, the term refers to family members who sponsor relatives under the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which repealed the national origins quota system and gave priority to family reunification. Sponsors also can be companies who bring employees to the United States, referring to visa requirements and application for a “green card.”

Sponsoring laborers was outlawed by the 1885 Contract Labor Law, which forbade Americans from engaging in labor contracts with overseas individuals prior to their immigration, and banned ship captains from transporting immigrants under labor contracts. Family Tree Magazine immigration expert Sharon DeBartolo Carmack explains, “Officials wouldn’t release an immigrant to a ‘sponsor,’ because there was worry of contract labor, white slave trading, prostitution, etc., especially if it was a woman traveling alone. It still went on, but underground. That’s why passenger lists began reporting who paid for a traveler’s voyage.” Women traveling alone or with small children were often detained until a husband or male relative arrived to collect them.

You may have heard that during the period of mass immigration through Ellis Island, beginning in 1892, US arrivals with little funds had to rely on a sponsor to enter the country. “The amount of money they had to have on them—perhaps $30—depended on the time period, and if they didn’t have it, they were supposedly deported,” Carmack says. Immigrant aid societies sometimes served as informal sponsors.

The term is also used in naturalization for people who could attest to how long the immigrant had lived in the United States.

Answer provided by David Fryxell

A version of this article appeared in the January/February 2014 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: How did sponsoring immigrants work in the 1880s?

A: Sponsoring an immigrant (that is, paying for another person’s passage to America with the condition that he or she works off the debt upon arrival) is an old tradition. Many arrivals during the Colonial period had their passages paid in exchange for a seven-year period of servitude known as an indenture. This custom persisted into the 19th century, providing newcomers with food, shelter and clothing, in exchange for work and training in new trades. Sounds like a good deal — but if the immigrant didn’t meet the terms of the agreement (often it was more like slave labor with minimal freedom), he risked fines, imprisonment, whippings, disfigurement or additional years of indenture.

Congress legalized contract labor for immigrants in 1864, then flip-flopped and outlawed such contracts 21 years later. As a result, many immigrant sponsorships simply went underground. Because the practice was illegal, the odds of finding a paper trail are slim — unless your ancestor or his sponsor was caught. Passenger-arrival lists won’t be of much help to you, either: Officials didn’t begin asking immigrants who paid for their passage until 1903.

If your ancestor arrived before 1885 and you suspect he or she was a contract laborer, you’ll want to read social histories for your relative’s ethnic group to determine what organizations and businesses may have advertised or recruited immigrants in the old country. Also take note of the place your ancestor first settled in America and the type of work he did. Say your ancestor worked as a laborer for a railroad company upon his arrival. You could check with the railway company’s archives or museum, or write to the state historical society to find out who keeps related records. Availability varies from one company to another since not all organizations retain their records or make them publicly accessible.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

A version of this article appeared in the August 2006 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: I would love to know how much it cost for my grandparents with their four children to sail from Bremen to New York in 1896. Any suggestions where could find this information?

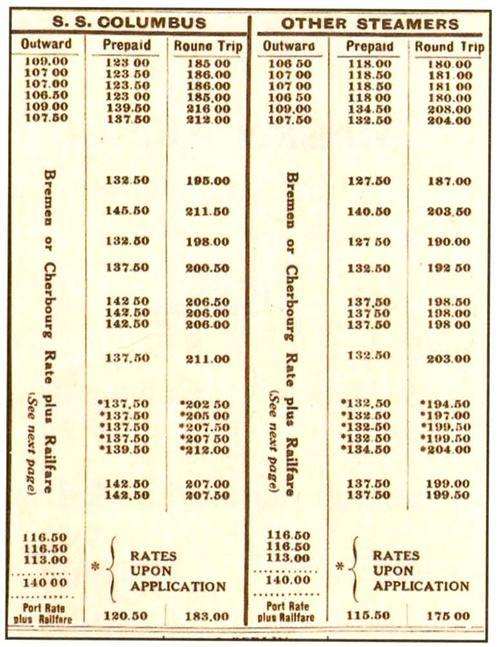

A: The cost to travel from Europe to America varied by the class, the departure port and the destination, just as today we have different fares to travel by air. Around the turn of the 20th century, a typical steamship one-way passage was from $10 to $35 for third class (steerage), $40 for second class and $80 for first. But just as airline-ticket costs fluctuate today, prices rose and fell when our ancestors came to America by ship. It might be more costly to go during a particular season than another.

If you know the name of the ship, the steamship line and precisely when your grandparents came, you might be able to find more specific costs by contacting maritime museums, such as The National Maritime Museum or Mystic Seaport Museum. Although the company doesn’t do research, New Steamship Consultants’ ocean liner memorabilia website sells brochures listing steamships’ schedules and fares. You can also try contacting the steamship line directly, if it’s still in operation. Most published sources about the immigrant experience contain the average fares as mentioned above.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

A version of this article appeared in the April 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Q: My problem is that the US and Irish records I need to find my family were destroyed in fires. I know my great-grandfather died on the ship coming over to the United States. Is there a website or other source that lists deaths on ships?

A: What a wonderful idea! Someone should compile a list of all those who have died aboard ship coming to America. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been done yet, either in print or online. I checked with two Irish experts, two Internet genealogy gurus, TheShipsList Home Page and Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild. None of these resources were aware of any such compilation, either.

Passengers who died aboard ship were recorded usually on the last page of the entire manifest, or a notation might have been made on the passenger’s entry on the list. Their names should be indexed along with other passengers. Not all ports and time periods have been indexed, however. For more information on using passenger lists and indexes, see A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Immigrant and Ethnic Ancestors (Betterway Books).

I find it unusual that all the US and Irish records you need were destroyed in fires, since many people are successfully doing Irish immigrant research. My suggestion would be to consult two primary works that will tell you whether the records you need still exist, and if they don’t, other research strategies and records that might indirectly give you the information you seek: A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Irish Ancestors (Betterway Books), by Dwight Radford and Kyle Betit, and Discovering Your Immigrant and Ethnic Ancestors mentioned above.

Answer provided by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack

A version of this article appeared in the June 2001 issue of Family Tree Magazine.