Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Whenever I was trying to decide what to pack for a trip, Mom always told me, “It’s better to have it and not need it than to need it and not have it.” Because of this bit of common sense, I now fork over checked-baggage fees whenever I fly. No doubt the adage, which expresses a truth based on practical experience, was handed down from her mother and her mother’s mother and her mother.

Our ancestors shared these short bits of wisdom and guidance with younger generations. We’ve come to know them as proverbs. Some cross into many cultures, usually with slight variations, but each one carries a lesson.

Certainly there’s no better time for a time-tested truth than when you’re flat up against that proverbial brick wall in tracing immigrant ancestors and kin in the old country. As the Swedes would say, you can’t prevent the birds of sadness from passing over your head, but you can prevent them from nesting in your hair. Translated into genealogy lingo, that means: You can’t avoid hitting a brick wall in your search, but you can find ways to surmount it.

Your ancestors’ sage words, viewed through a genealogical lens, can help you climb over those brick walls. So let’s put that advice to use: Here are the genealogy research truths behind 13 ancestral proverbs from around the world.

1. Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.

English

This English warning applies when a relative or website proffers a complete genealogy back to Creation (or some other improbably distant date). Be aware of possible errors—especially if that genealogy purports to have scaled a brick wall but cites no source. Although you’d hope other genealogists would be meticulous about properly linking one generation to the next, alas, many are not. Some are merely eager to gather as many names as possible or to show a prestigious lineage. So beware of genealogists bearing faulty genealogies, and double-check the facts using original records.

2. A journey of a thousand miles starts with one step.

Chinese

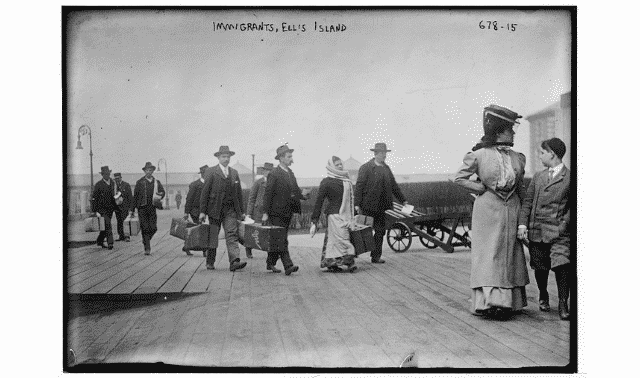

Whether your ancestors came from China, where this proverb is popular, or another country, sooner or later your research will leap from America to your ancestral homeland. But as the Irish would say, it’s no use going to the goat’s house to look for wool.

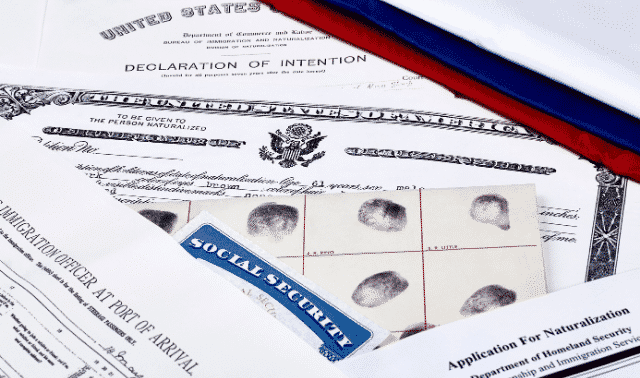

Generally, you won’t be able to begin research in a foreign country without knowing precisely where your ancestor came from—as in a town, city or county name. If you still need that bit of information, scour records your immigrant ancestor made in America for clues that’ll point to his or her origins. In particular, look for naturalization records, death certificates and obituaries.

3. Not the cry, but the flight of the wild duck leads the flock to fly and follow.

Chinese

If searching your ancestors’ records hasn’t revealed their hometown in the old country, heed this Chinese proverb. Many immigrants traveled to America in a pattern called chain migration: A few people would immigrate, then others in their family or town would follow.

When you’re stuck, research relatives and neighbors to see where they came from. Even though your ancestor might not have left the information you need in his own documents, a relative or close associate might have been so kind. When I began researching my Italian “chain,” I knew of three relatives who came to America. Following the chain, I discovered four more relatives:

- Isabel (Veneto) Vallarelli was listed on a March 1916 passenger list as going to join her son-in-law Salvatore Ebetino in Rye, NY. Salvatore Ebetino was on an April 1906 passenger list, joining his brother-in-law Albino DeBartolo of Harrison, NY.

- Albino DeBartolo was on a September 1905 passenger list, joining his cousin Giuseppe Lambarella of Harrison, NY.

- Giuseppe Lamporelli was on a March 1905 passenger list, joining his cousin Francesco Lamparelli in New York City.

- Francesco Lamparello was on a December 1904 passenger list, joining his daughter Giacchina Lamparello in New York City.

It’s easier when you’re dealing with immigrants who came in the early 20th century, because passenger arrival lists of this period record who the immigrant was joining in America.

4. A tiger dies and leaves his skin; a man dies and leaves his name.

Japanese

The Japanese knew names are important. Although in genealogical research the spelling of a name can vary widely (as in the Lamporelli example above), it’s critical to know your immigrant ancestor’s name in the old country—not necessarily the one he used in America—if you hope to find him in the records there. But the Irish knew that even if you put silk on a goat, it’s still a goat. Sometimes ancestors shortened their names, such as Adamczyk to Adams; in other cases, they adopted loose translations, as in Giuseppe Verdi to Joe Green. Check with family members to see if they’re aware of any name changes. Most likely, you’ll find the ancestor’s original name on passenger lists and naturalization documents.

5. Ask about your neighbors, then buy the house.

Jewish

Do you lose your immigrant ancestor from one census to the next? Doing as this Jewish proverb suggests could help. One trait is common to almost all immigrants, no matter when they arrived or what their ethnic background: Upon arrival, free people often settled with friends and relatives from the homeland.

Families and neighbors tended to migrate on to other places together, too, so track those folks if you “lose” your ancestor. In Ireland, if one sheep puts his head through the gap, the rest will follow. Watch for clusters of the same neighbors or relatives in census records and property deeds. Track your ancestor’s brothers, sisters and in-laws. Where they go, your ancestor probably went, too.

6. Look for the good, not the evil, in the conduct of family members.

Jewish

That’s probably good advice for getting along with living relatives, but flying in the face of this Jewish proverb can be productive when you’re tracking dead people. The ones who got into trouble with the law or with their neighbors usually left more records. In researching a family member’s “evil conduct,” you might find your brick wall ancestor was a victim or testified on behalf of the wayward one.

Sometimes the ancestor didn’t do anything wrong, but she died in an unusual or mysterious way that triggered a coroner’s inquest: Mary Hogan, born in Ireland, died in New York City from apoplexy in 1847. Her sister, Catherine Hogan, told the coroner they had arrived in the United States about six weeks earlier on the Alexander. This might be the only place the immigration details survived. Court records, newspapers and coroners’ inquests are prime resources for tracking the black sheep in your family.

7. Despair doubles our strength.

English

You might need to put this English proverb into practice when trying to find arrival dates and ports. Determination is sometimes the only way to find answers. Narrow the date of arrival by searching every possible record the immigrant created within the time frame you think he came to America. City directories can help because they were usually published annually, but remember that many immigrants don’t show up in them for several years after arriving.

Twentieth-century censuses provide the year of arrival, and in some cases, this may be the best you can get. You might not find a passenger list even when you have an exact date and port. Bavarian immigrant Julius Ney’s naturalization record pegged his arrival on July 23, 1854, through the port of New York, but I still don’t have his immigration record. I’m determined to keep watching for newly available resources and indexes, though, and I continue the search for others with early connections to Julius.

8. You may go where you want, but you cannot escape yourself.

Norwegian

This Norwegian proverb reminds us that our ancestors didn’t necessarily leave the old ways behind when they moved to America. Or as the Irish version goes, you can take a man out of the bog, but you can’t take the bog out of the man. Historians have found that the first generation of immigrants typically tried to maintain native customs. Remembering these social customs could help you solve genealogical riddles.

In the 1900 census, 10-year-old Lillian Denny lived with her uncle and aunt John S. and Dollie Stephens in Hopkins County, Texas. But is John the brother of Lillian’s mother? (The two different surnames tell us Lillian’s father wasn’t John’s brother.) Or is Dollie a sister to one of Lillian’s parents

Guessing that Lillian was in the care of her mother’s sister—more in accord with social custom—I found a marriage record for John Stephens and Dorothy B. Minter. Now I had a potential maiden name for Lillian’s mother. Another search of Hopkins County marriages revealed a J.H. Denny marrying Mattie E. Minter, who turned out to be Lillian’s parents.

9. Prepare your proof before you argue.

Jewish

Citing the sources of your information will help you stay on the right research track and keep you from retracing your steps. But more important, keeping track of documentation and making a chronology for a difficult ancestor can help you evaluate your findings and ensure that you aren’t, say, tracing two same-name people in the same community. And if your genealogy disagrees with Great-aunt Alice’s, just as this Jewish proverb advises, you’ll have the evidence you need before you debate.

10. Often a cow does not take after its breed.

Irish

Some of our immigrant ancestors took great care to assimilate into their new society, doing everything possible to be “American” and even disassociating themselves from their national origins. Sometimes people tried to disguise ethnic origins that suffered from prejudice: Decades ago, for example, people were often reluctant to admit having American Indian blood.

Many an immigrant found that no one in his new country could pronounce his name, so he changed it. The name “Toliver,” common in Virginia, is one example: The Colonial-era immigrant’s Italian surname was actually Taliaferro. But it was too difficult for Virginians to pronounce, as the story goes, and it evolved into the English-sounding Toliver. So pay attention to this Irish proverb and be on the lookout for clues that might point you in an unexpected direction.

11. There are many ways of killing a pig other than by choking it with butter.

Irish

What the Irish are saying here is to get creative. One approach to a brick wall problem might not work, yet another one will. That’s why networking with other genealogists is critical. Each person has different research experience because his family history is different from yours. Learning from the experts can help you expand your repertoire of research strategies, too. Two must-read books for solving brick-wall problems are Marsha Hoffman Rising’s The Family Tree Problem Solver (Family Tree Books) and Emily Anne Croom’s The Sleuth Book for Genealogists (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

12. Courtesy that is all on one side cannot last long.

French

After you’ve done substantial research, consider posting your findings online or in print to help others. Giving back to the genealogy community is an important aspect of sharing, as the French remind us with this proverb. Plus, when you make your research available, it might help you discover others who are working on the same branch of the family. There’s no better way to bust through a brick wall than making your research available and reaching as many people as possible.

But the Spanish also said that one falsehood will lead to another. Before you publish your genealogy findings on a website or in a book, proofread your work. Better yet, have another genealogist proofread it for you, double-checking that dates make sense, generational connections are sound and spellings are correct. As many have learned the hard way, an error in a genealogy posted online or in print may be impossible to correct, and it will be repeated in others’ genealogy research.

13. Even a blind squirrel finds a nut once in a while.

English

The English folks who came up with this gem would tell you that sometimes serendipity, gut instinct and simple logic are your biggest helpers in breaking through brick walls. Write out your genealogical dilemma as if you were writing that person’s biography. Are there gaps in the information? Does everything make sense? Irish immigrant Daniel “Dinnavin” (Donovan) signed his name to receive land grants in Allamakee County, Iowa, in the early 1850s. In the late 1840s, Daniel “Dunivan” received a land grant in bordering Clayton County, from which Allamakee County was formed. Same man? Perhaps not, because this second Daniel signed with a mark. Don’t ignore those little nuts.

The truth is genealogical breakthroughs rarely happen in a flash of brilliance. Instead, the dogged, repeated application of these time-tested proverbs is what will bring you answers. And the results will be worth it: As the Spanish say, patience begins with tears and ends with a smile.

Quiz: Match each old proverb with its genealogy translation

Now that you’ve had some practice, see if you can match each proverb with its genealogy research truth. The answers are below.

Proverbs

- A cat with gloves never catches mice (Greek).

- Poor men take to the sea, the rich to the mountains (Irish).

- Don’t cry “hurrah!” till you are over the ditch (German).

- The only truly dead are those who have been forgotten (Jewish).

- Don’t put all your eggs in one basket (various).

- Comparison is not necessarily proof (French).

- A little thing can ruin the whole thing (Norwegian).

Genealogy research truth

a. Take care that you’re tracing the right ancestor, not someone with the same name.

b. Make sure newly discovered facts and dates fit with what you already know from other sources.

c. Look for the same information in a variety of records, rather than relying on just one. The more sources you can find for Great-grandpa’s birth year, the sounder your conclusion that it was 1881.

d. Don’t limit yourself by assuming a record won’t tell you anything new. You never know what’s on a record until you look.

e. A significant error in the genealogy you post online—like inadvertently skipping a generation—may call all your findings into question. Have another genealogist review your work.

f. Your immigrant ancestor likely wasn’t the firstborn son. Firstborns typically inherited the land and stayed in the old country (so you might still have relatives there).

g. Don’t neglect female lines or siblings who never married. They may hold the key to unlocking information on other relatives.

Answers: 1. d, 2. f, 3. b, 4. g, 5. c, 6. a, 7. e

A version of this article appeared in the September 2009 issue of Family Tree Magazine.