Everyone has their “go-to” record collection for research. But what do you do once you’ve looked at it? You see a name, identify your ancestor, and maybe gain other details like a location or date. What do you do next? How does finding information on a document enhance your research? Is it another lead? Have you considered its accuracy?

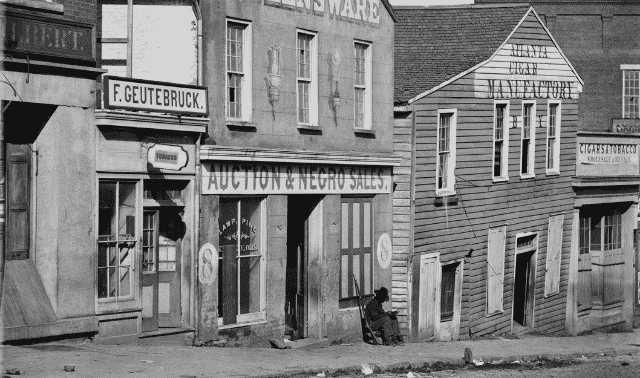

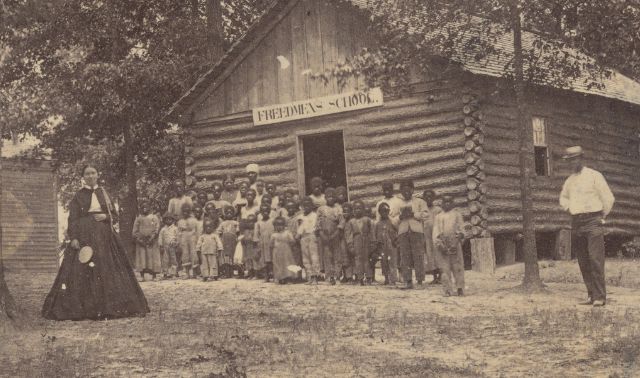

My work has included locating descendants of enslaved laborers for the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers. African American genealogical research, like that required for this project, has its challenges. But I found one key collection—a must for researching African Americans prior to 1870—the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

The collection is not new, though recent digitization efforts by FamilySearch and Ancestry.com have made it more accessible. But it does combat the myth of African Americans not being able to locate information on their ancestors prior to 1870.

As with other “go-to” resources, the key to using Freedmen’s Bureau records is knowing what to do with information once you’ve found it. This guide to understanding the Bureau and the records it created will help you get started.

The History of the Freedmen’s Bureau

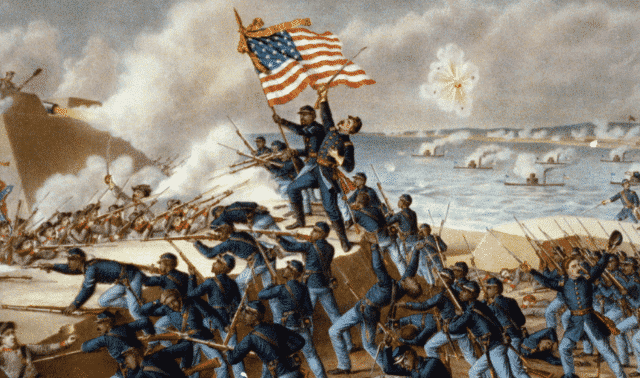

The organization was formally called the “Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands.” As its name implies, the Bureau was chartered in 1865 to provide aid for refugees (most of them white) and newly freed African Americans (Freedmen), as well as manage property confiscated during the Civil War.

Relief assistance included education, health care, food, transportation, rations, employment, clothing, the construction of refugee camps, legal recognition of marriages and more. The Bureau also helped Black servicemen and their heirs collect pensions and backpay.

As a federal agency, the Bureau was operated by the federal government (specifically the War Department). Its records are thus in federal custody, categorized as Record Group (RG) 105. Records were created through the Bureau’s full lifetime (1865–1872), though “pre-Bureau” records exist as early as 1863 in Mississippi, Louisiana and Virginia (Ft. Monroe).

The Bureau faced many difficulties, from a lack of funding and staffing to violence by the Ku Klux Klan and other Southerners who resented federal help for Black people. Congress shut down the Bureau in 1872 amid flagging support from Northerners.

The National Archives (NARA) has created “descriptive pamphlets” about the Freedmen’s Bureau in each state involved. The pamphlets describe, in detail, field office information and location, as well as the contents of what is on each roll. For example, the Virginia pamphlet reads:

“The Freedmen’s Bureau’s efforts to provide relief to both blacks and whites in Virginia began almost as soon as Orlando Brown assumed office as assistant commissioner for the state in June 1865. From late summer to early fall 1865, the Bureau issued more than 350,000 rations at a cost of nearly $33,000. By mid-October 1865, however, the number of rations issued had declined from a previous 275,000 to less than 236,000. During the same period, the number of people receiving rations decreased from 16,298 to 11,622.”

As previously mentioned, the Bureau operated in several areas of society. Documents include marriage records, reports, letters, ration notes, labor contracts and land applications. Taken together, they can provide you with:

- Times, dates and places for major life events, including births and marriages

- Residences, including former locations before the Civil War

- Relationships and names of family members

- Ages

- Medical conditions

- Information about military service

- Race

- Occupations

- Names of former slaveowners

How to Access Freedmen’s Bureau Records Online

Genealogy is ultimately about time, place and asking a lot of questions. One of those questions: How do I access information?

Let’s first look at how the military was organized. The department had field offices scattered across the South, covering specific places, usually cities, towns or counties. Overseeing field offices were the sub-assistant commissioners, then the assistant commissioners at the state level. Assistant commissioners reported to headquarters in Washington, DC.

The National Archives assigned separate microfilm numbers to state field office records:

- Alabama (M1900)

- Arkansas (M1901)

- District of Columbia (M1902)

- Florida (M1869)

- Georgia (M1903)

- Kentucky (M1904)

- Louisiana (M1905)

- Maryland and Delaware (M1906)

- Mississippi (M1907; pre-Bureau records in M1904)

- Missouri (M1908)

- North Carolina (M1909)

- South Carolina (M1910)

- Tennessee (M1911)

- Texas (M1912)

- Virginia (M1913)

New Orleans has its own microfilm collection (M1483). Assistant commissioner and superintendent of education records are generally in separate microfilm collections.

Thanks to digitization efforts, you won’t necessarily need to consult the original microfilm. FamilySearch holds field office records and records of the assistant commissioner’s office for most states, organized by state/location of field office. The records aren’t fully indexed, but volunteers for the Freedmen’s Bureau Project created an every-name index; learn more about this and search the index.

In 2021, Ancestry.com compiled a centralized database of indexed Freedmen’s Bureau records. Though Ancestry.com is a subscription site, the 3.5-million-record collection is free to search.

You can visualize the Bureau’s work and determine where records are online for your area of interest at Mapping the Freedmen’s Bureau. (Read a tutorial to that site here.) The site also publishes the National Archives’ research guides.

Start Your Search

Here are some quick steps to get started in your search:

1. Read NARA’s guides to state records

Become familiar with what letters, documents and records are included. You might even find the collection contains a field office from another state.

2. Determine who you will research, and set a realistic goal

You can have more than one goal, but just make sure your goals are specific and short. Think about the key things you are looking for, such as: where a person was born; when and to whom they were married; the names of their parents and children (if any); the names of their former slaveholders (if any); and the places they lived.

3. Face your research challenges head on

You’ll encounter numerous challenges when researching African Americans prior to 1870, whether your ancestor was free or enslaved. Just a few of those challenges are:

- Records that were never created, or have since been destroyed

- Surnames changing over time

- The fact that African Americans were seen as property, not has humans (limiting their presence in records)

- Changing slaveholders

- 21st-century thinking that clouds your research

You can take on these challenges through what I call the three E’s: Expect challenges, embrace them, and let them enhance your research skills. Careful, thorough research (including seeking to understand the county/community and laws of the time) can help you do that.

4. Access the mapping site

Once you have a location, use Mapping the Freedmen’s Bureau to identify the nearest field office.

5. Scroll through images

From a field office page, the mapping site will take you directly to the National Archives or FamilySearch. Page through record images, looking for clues like familiar-sounding surnames or neighbors. The name-index will help.

6. Plan what’s next

As you locate new information, continue developing your research plan. Ask yourself questions about what those record details mean, and where they might lead you next. Create a timeline of information to identify next steps.

Sample Records

Let’s now take a look at several types of records you can find among the Freedmen’s Bureau’s collection.

Marriage Records

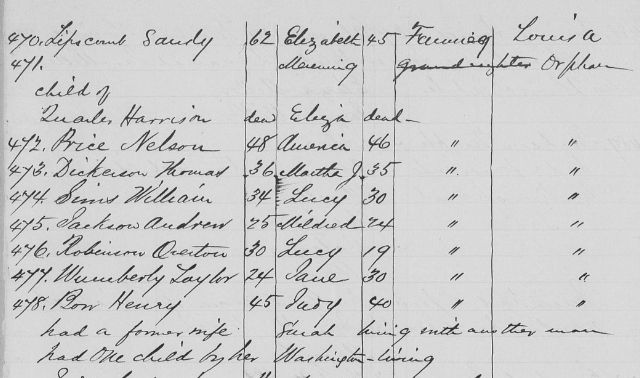

When taking a deep dive into Bureau records, you should start with what you know. Here’s what I knew about Nelson Price, who was a subject of my research.

Nelson Price was an enslaved laborer who was rented by Egbert R. Watson from Albemarle County, Virginia, to the University of Virginia in 1863. Watson also lived in Albemarle County, so Nelson would have been there during his enslavement.

Note that Nelson had a surname different than his slaveholder. Where did Nelson obtain his surname, then? An Ancestry.com tree for Watson’s family reveals Egbert’s mother’s maiden name was Price, providing one explanation.

But I wanted to learn something different: Did Nelson Price marry? He’s listed alongside six children in the 1870 census of Louisa County, Virginia, but no woman. Who was the kids’ mother?

I first need to identify a field office, and I have a couple different options. I can click Browse All Images on the FamilySearch collection for Virginia, which opens a list of field offices included in the collection. Or I can go to the Mapping Freedmen’s Bureau site and home in on Louisa County, Virginia, using the interactive map. Both indicate there was a field office in Louisa Courthouse, located in roll 104.

Clicking the Louise Courthouse link (on FamilySearch) or the microfilm rolls link (on Mapping the Freedmen’s Bureau) will take you to that part of the collection on FamilySearch. Roll 104 includes a register of Black persons married by the Virginia Assembly, effective 27 February 1866. Click that heading to browse images; fortunately, the collection has at least a name index, making it easier to read the handwriting.

Line 472 (page 24) lists a 48-year-old Nelson Price and his wife America, age 46. The quotation marks in the last two columns indicate Nelson’s information is the same as the line above him (presumably, line 470), so Nelson was a farmer that currently lived in Louisa County. Nelson’s age lines up with his listed age in the 1870 census, and I can estimate birth years for both him and America based on their ages in 1866.

Nelson and America’s children aren’t listed in the marriage register, but some other couples’ are. Other marriage records created by the Bureau might also indicate who either party was formerly owned by, how long the couple lived together, the ages of any children, and even notes about military service. All those details can spawn more questions.

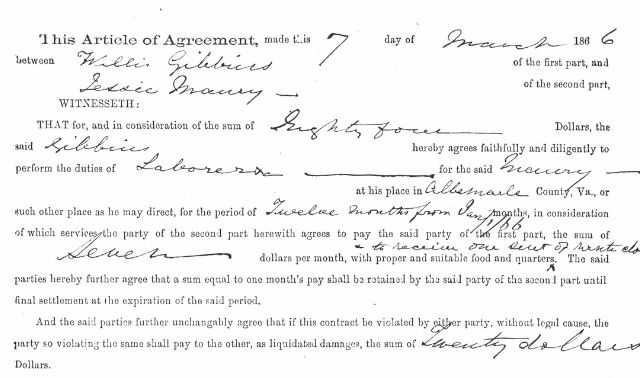

Labor Contracts

The Bureau also provided employment contracts for the formerly enslaved. Often, the agreement was between the freedman and his former slaveowner to do the same job as during enslavement, but now with pay. Details include the names of the parties, the date, a location and the terms of the contract.

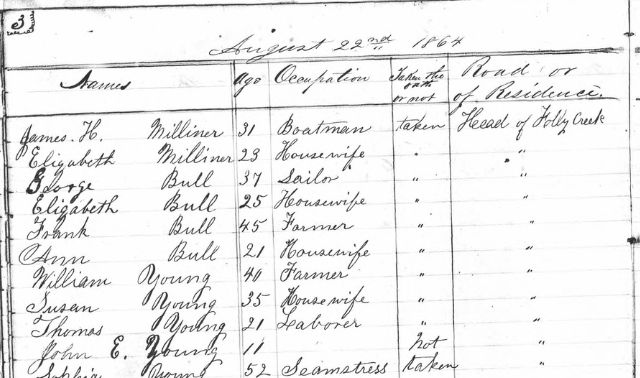

Oaths of Allegiance

The Bureau kept registers of people who were required to take an oath of allegiance to the United States following the Civil War. Details include names, ages, occupations, roads or residences, genders, a section for remarks and (of course) whether the person elected to take the oath. This acts as a useful kind of enumeration, which might give you the names of former slaveholders in a county or the location of plantations.

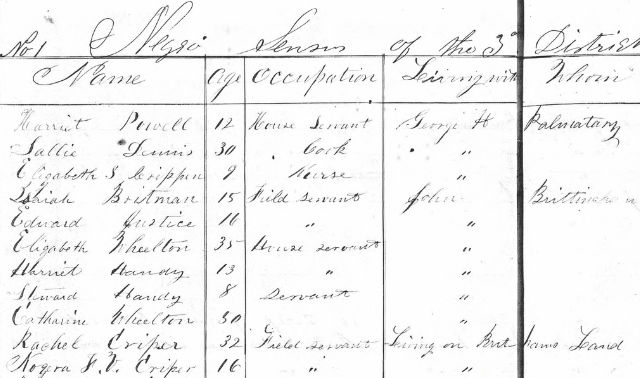

Censuses

Though not taken in every county, the Freedmen’s Bureau’s self-conducted censuses can also be helpful, especially when filling in the gap between the 1860 and 1870 federal censuses. Accomack County, Va., for example, created two separate schedules during the 1860s: one for white communities and another for Black communities. Listed are names, ages, occupations, locations and any notes. Taken together, names and ages can suggest family units.

Correspondence

Among the Bureau’s documents are letters and administrative documents, both between government officials and petitions from civilians.

In one series of letters to and from a field office in North Carolina (not pictured here), two parents ask the Bureau to assist them in recovering their twin children from their former slaveowner, who concealed them from authorities after the war was over. The parents were ultimately unsuccessful, and studying the correspondence illustrates both the Bureau’s strengths and limitations in advocating for the recently enslaved.

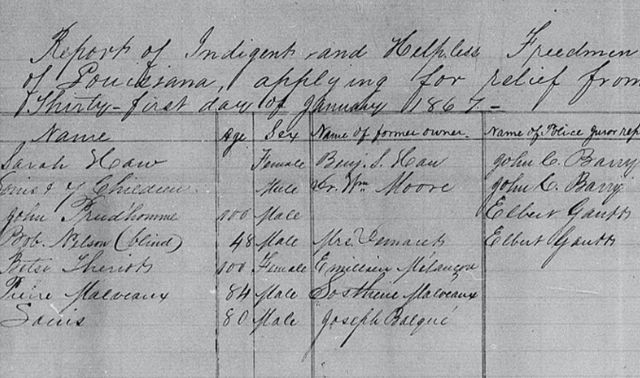

Ration Reports

To facilitate distribution of food and supplies, the Bureau created ration reports that provide names, ages, sex, names of former slave owners and dates.

The sample record above includes two 100-year-olds on a report from St. Landry Parish, La., dated 1 January 1867. Think about the life lived by one of them, Betsy. She was born in 1767—before the United States was even a country. She probably spent her whole life enslaved. She may have even come over on a slave ship, and she lived long enough to see her freedom.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the May/June 2022 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025