Editors’ note: When this article was written and published, Google’s AI tool was known as Bard. In February 2024, it was renamed Gemini. It’s more than a name change, however, as the entire experience—user interface and backend—has been updated. Any references to Bard in this article hopefully can now be used in the same way with Gemini.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a difficult topic to avoid these days. You read about it in the news and see it mentioned in social media and even in day-to-day conversations with family and friends. Should you be concerned? Do you know what AI really is? Should you be using AI in your genealogy and family history research?

In this article, we will explore what AI entails, how the worlds of AI and genealogy often intersect and even how you could harness its powers to assist you in your genealogy research.

The Basics of Artificial Intelligence

What is AI?

AI stands for Artificial Intelligence and represents computer-based systems that can “mimic” human intelligence and thus perform human tasks.

A task could be as simple as entering a customer service-related question on a company’s website and having AI generate a response. Now that might appear like simple stuff—the computer just “looks up” a response and posts it to the chat panel. But AI-based systems might prompt you with more questions in order to generate the most helpful answer. And the system could capture your questions and “learn” more about the way you use the product in order to better respond in the future.

The most discussed features of artificial intelligence are “deep learning” and “generative AI.” Deep learning mimics the human brain in that it looks for patterns, using vast amounts of information to interpret photos, audio and text. Generative AI actually “generates” new photos, audio and text, based on information provided by the user, and uses its own database of “training data” to understand patterns and create output that matches the user’s query.

AI Platforms

While several of the big names in genealogy like Ancestry.com and MyHeritage are incorporating artificial intelligence into the features they provide to users, there are some popular general-use AI platforms open to the public that you might want to consider using. Some of the most popular platforms include:

- Bard: Developed by Google, Bard describes itself more as a conversational chatbot that can “generate text, translate languages, write different kinds of creative content, and answer your questions in an informative way.” Bard is the main competitor to the ChatGPT platform.

- ChatGPT: Meaning “Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer,” ChatGPT is the most popular publicly-accessible artificial intelligence platform.

- Perplexity: A relative newcomer in the world of AI platforms, Perplexity presents a curated list of sources when answering user queries.

Current Uses

Believe it or not, genealogists have already benefited from artificial intelligence whether it is just spelling and grammar check in Microsoft Word when writing a family story or genealogical report. Below are some specific ways in which AI has helped carry out significant projects and functions in the world of genealogy.

- Family photos: Over the past three years, MyHeritage has been offering a variety of photo enhancement tools, including ways to colorize images and make them clearer. It has also released Deep Nostalgia, a unique feature that can “animate” an ancestor based on a photo and even help determine the date of an image based on characteristics such as fashion styles, hair styles and more. Finally, its recent Reimagine tool offers all these tools in an easy-to-use app.

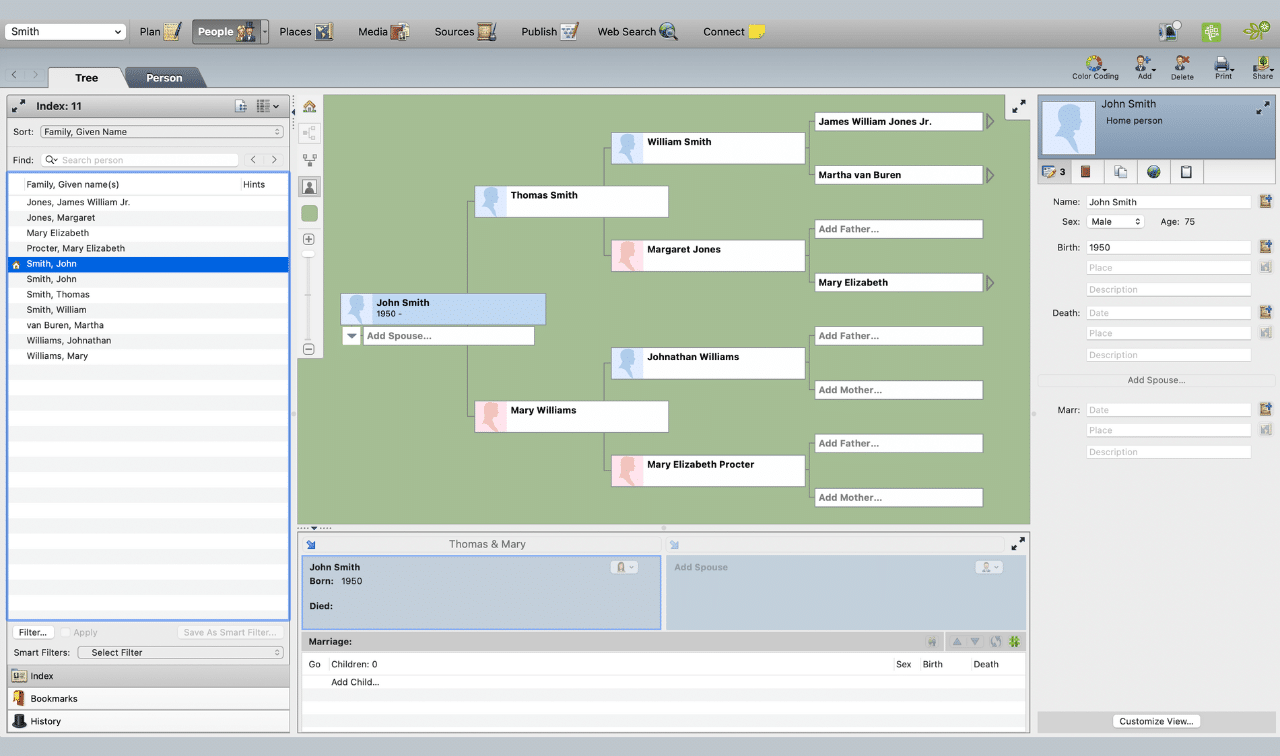

- Transcription: The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), in conjunction with Ancestry.com and FamilySearch, used artificial intelligence to index the 1950 US Census population schedules released in April 2022. Entries made by enumerators were scanned and transcribed then released for use at a much faster rate than what was accomplished with manual indexing performed for the 1940 US Census release in 2012. For the 1950 US Census, users were encouraged to review the transcriptions and submit corrections as part of a community effort by genealogists and other researchers.

- Suggesting records: Ancestry.com and other genealogy platforms have been listing “related” or “suggested” records in the sidebar of the web page when a user is viewing a record as part of a search. In addition “hints” will often pop up suggesting records and family trees that a researcher might want to review due to similarities in data.

- DNA matches: With over 30 million people having used personal DNA testing kits, 23andMe, AncestryDNA, FamilyTreeDNA and MyHeritage all leverage AI to find connections between testers based on shared DNA data. Given the sheer amount of information involved, these match results are only possible with artificial intelligence.

AI: Benefits and Concerns

With all the “hype” surrounding artificial intelligence, it can be difficult to critically measure the technology’s pros and cons, especially when misinformation is still prevalent. Below I outline both potential benefits and drawbacks of AI, especially when it comes to its use for genealogy.

The Benefits

New technology often brings with it endless opportunities for exploration, and AI is no different, especially when it comes to searching for ancestors. Here are some notable benefits of using AI for this purpose:

Analyzing vast amounts of data: There is a lot of information available online for genealogy research, but humans cannot possibly analyze that information as quickly as artificial intelligence. Leaving this task to AI can lead to the discovery of new connections between data points and better understanding migration patterns and motivations, F.A.N. club relationships, the impact of social history on our ancestors, and more. In sum, what is not obvious immediately to our human minds can be quickly determined by using artificial intelligence.

Block chaining: I’ve long been an advocate of using block chaining for genealogy data, especially DNA data. Block chaining involves tagging data with specific information including ownership and tracking its use by others. The chain of use is kept in a public “ledger. The owner can better understand who is using that data and why, which is a common concern when it comes to DNA testing and who has access to that personal information.

Translation and transcription: As already demonstrated with the release of the 1950 US Census images, AI promises to make the transcription and translation of record images faster and easier. I recently uploaded a newspaper clipping from a historical newspaper that has not yet been digitized, and the AI platform did an amazing job in transcribing the content (see below for more details, as well as the newspaper clipping in question).

Timelines and mapping: For those genealogists who want to fill in the “dash” between an ancestor’s birth date and death date, artificial intelligence can help build complex timelines and “map” event dates to locations for a better understanding of how our ancestors lived.

The Concerns

Copyright: Many copyright and intellectual property issues related to AI have popped up in the past year. U.S. courts have ruled that content created by artificial intelligence cannot be copyrighted. In addition, several content creators have sued major AI platforms such as ChatGPT and Bard for scraping copyright protected content from the internet to help create AI-generated content.

Privacy violations: Artificial intelligence can quickly collect data entered at genealogy platforms when performing research and creating family trees. In addition, users are tracked as to searches performed and this data is analyzed to create new features and products. More importantly, DNA data is captured and despite privacy policies that ensure the use of only metadata, recent computer hacks at vendors such as 23andMe have caused a steep decline in the number of people using personal DNA test kits.

Lack of transparency: One of the most pressing challenges for AI users is the inability to determine the source of the reference material used when generating content. Another issue: recognizing AI-generated content. Most users are not adding source citations to AI-generated content or watermarks to AI-generated images.

Bias: Studies have proven that many AI platforms can be biased, especially since content used as reference material is supplied by humans. The same biases we see in terms of race, gender, and age are easily replicated by artificial intelligence. Recent examples have included a bias towards generating white or Caucasian faces rather than people of color when asked to create certain types of images.

False information: When one uses AI to gather information, who or what is determining what is true and what is false? A recent example of a law firm submitting a legal filing created by artificial intelligence—resulting in a list of fictitious court cases to support legal arguments—demonstrates the problem. This is another reason that “human review” is often required before relying upon AI-generated content.

High costs: While not often discussed, deploying artificial intelligence can be expensive for many organizations and individuals, resulting in higher prices for the genealogy consumer. The machines and servers used for AI processes require more powerful chips as well as simply just more power to run. Besides an increase in costs, there are environmental and climate impact costs through the need for more energy to power AI computers.

More on Copyright and AI

There are several issues involving artificial intelligence and intellectual property that should concern you. Some of these issues have already been discussed and decided by agencies and courts. Many of them, however, have not been resolved.

The two main issues are:

AI-generated content: Can content that is created by artificial intelligence based on your query be copyrighted? What if you ask Bard to generate an image of what your 5th great-grandfather who fought in the Revolutionary War might look like? And the query was based on your research information as to his physical description taken from letters or diaries? Who owns the resulting image?

Currently, lower courts have stated that AI-generated content cannot be copyrighted since there is no human author. Much like the case of the “Macaque monkey selfie” where a monkey took a photograph of itself using equipment set up by a British photographer, there is no “consent” involved. Animals cannot give consent or enter into a legal agreement, so it was determined that the resulting image was copyright free. The courts are using the same method to determine who owns that ancestor photo you generated using artificial intelligence.

Source or reference content: Another common copyright concern involves how AI platforms are gathering their reference information used to generate content. When one asks ChatGPT to generate a sonnet about genealogy in the style of Shakespeare, the algorithm must have Shakespeare’s sonnets in order to understand his writing style and create the genealogy sonnet.

In this case, all of Shakespeare’s works are in the public domain according to US copyright laws. But what about an author such as Tom Clancy or Stephen King whose works are still under copyright? And what about AI-generated images or even recordings based on a celebrity’s image and voice? Most platforms are not transparent as to what reference content is being used and how it was acquired. This becomes an ethical issue and only furthers general fears about artificial intelligence.

Your Personal Information and AI

Some common question many newcomers to AI have are simple: What query information is captured by AI platforms? How is that information used? As a rule in genealogy, personal information for living persons is never disclosed publicly in family trees. But what if you create a query for a living person that includes their birth date or current address? What does Bard or ChatGPT do with that information? Do they save it and use it to train their platform to respond to future related queries?

ChatGPT and other platforms do have ways for you to keep your input data private, but these preferences or settings are not by default. To avoid any uncertainty, you should always review a platform’s Terms and Conditions or Privacy Policy, which will typically include language regarding how personal information is stored and used.

The Ethics of AI

When you hand over any task to an artificial intelligence platform, the issue of trust comes into play, especially since you are essentially allowing the platform to perform a task for you. How do we know there isn’t some bias towards a person based on geographic location or other information?

One main concern is the lack of transparency overall in the AI world. Initial versions of ChatGPT did not disclose the reference information for generated content. Currently, the platform does use footnotes for some content with links to the information it used in the algorithm to answer a query.

What about full disclosure when using AI-generated content? Should genealogy societies be concerned about article or presentation submissions being generated by ChatGPT or another platform? This concern carries over to AI-generated images as well. Should digital watermarks be required for all photos, videos, and audio recordings generated by artificial intelligence?

The myriad of ethical questions and concerns has fueled a push for governmental regulations. The European Union has already passed a basic set of regulations and the United States government—including the US Copyright Office—are working on implementing regulations. Regulations may be needed to assure users of AI, but they also could be too restrictive so as to deter further growth of the technology.

My recommendation is to always disclose when you are using AI-generated content and include source citations when possible. Below is a guide to help you cite properly.

Source Citations

Those new to genealogy and family history quickly learn the importance of source citations in proving relationships as well as facts about an ancestor. Usually, source citations document how we find and use records such as census population schedules, death certificates and even letters or diaries.

For the most part, you won’t find records when making queries on an AI platform. But you may find information that serves as a clue for further research or, more likely, as social history about how an ancestor lived. In these situations, a method of citing AI-generated content is needed.

Citing sources need not be intimidating or time consuming. Stick to the basics: the information found, how it was found, information about where it was found, and locator data so another researcher can find the information.

For artificial intelligence content, here’s the formula you might consider using as proposed by the Modern Language Association of America (MLA):

“[QUERY]” prompt. [NAME OF AI PLATFORM], [DATE OR VERSION OF PLATFORM], [NAME OF AI COMPANY], [DATE OF QUERY], [PLATFORM URL]

So, if I asked Bard to determine the value of my great-grandfather’s home in the 1930 US Census listed as $80,000 in 2023 dollars, here is the source citation I would use:

“Value of home in the 1930 US Census listed as $80,000 in 2023 dollars” prompt. ChatGPT, 25 September 2023 version, OpenAI, 1 October 2023, https://chat.openai.com/share/712a395f-c0be-4c42-86c0-72037d7c5ba4

Examples of Genealogy Projects Completed With AI Tools

Above, I showed examples of how AI has assisted big-name companies and organizations with major genealogy functions. Here are a few examples of how you yourself can use the major AI platforms when searching for ancestors, as well as some personal examples from me.

Social history

Hugo Freer, my 9th great-grandfather, settled in New Paltz, New York, along with other Huguenot settlers about 1675. His house (the Freer-Low House) built in 1699 is still standing. Wanting to know more about how Freer lived, I used this query at ChatGPT: What was life like in New Paltz, New York, in 1699?

The information provided is extensive but also rather generic for any location on the East Coast of the United States. In addition, the section on housing states the use of wooden buildings with thatched roofs, when in fact New Paltz was known for its early homes built using stones excavated from the fields.

Record Sets

My 3rd great-grandfather Gustave Henneberg arrived in New York from Germany about 1881. I posed the following query at Perplexity in order to determine which records I should use for research purposes: What records can I use to locate an ancestor who arrived in New York City in 1881?

Perplexity bills itself as different from ChatGPT and Bard in that it curates sources which are presented at the top of the generated content.

Transcription

Robert Austin was the brother of my great-grandfather John Ralph Austin (1896-1976). Robert drowned in 1924 at Long Beach, New York, while trying to rescue a child. I uploaded a newspaper article about the incident to Bard and in the query prompt entered Transcribe.

Bard did a great job despite the article image having some clarity issues!

Relationship Clarification

During my genealogy research, I’ve located a person to whom I’m related via a maternal great-grandmother. The document I am using for research states that the person was my great-grandmother’s niece. I want to determine how I am related to this person. Prompt: How am I related to my great-grandmother’s niece?

Future Uses for AI in Genealogy

The concern over artificial intelligence in general, and specifically in family history research, is similar to the concern over social media almost 15 years ago. Remember when genealogists were worried about Facebook and X (formerly known as Twitter)?

We are experiencing the “First Phase” of using artificial intelligence when it comes to genealogy and family history research. Five years from now we should be in “Second Phase” mode. What does this mean?

Remember when Netscape was THE browser everyone used when the Internet became popular in the early 1990s? The second phase of a new technology usually brings vast improvements in terms of functionality, ease-of-use and value.

Here’s a short list of what you can expect to see in the next five years:

- DNA triangulation tools that will quickly determine relationships on family trees.

- Conversion of handwriting into searchable text including older forms of English and German handwriting.

- Creation of source citations for a variety of records using specific formats such as MLA, Evidence Explained and AP style.

- Discovering connections between F.A.N. club members using digitized historical newspapers content and other records.

- Identification of ancestors in old family photos based on “traits” such as facial features including connecting family members based on similar traits.

- Suggesting records for expanding genealogical searches including those records not yet digitized.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence may seem valuable in its scope but also intimidating in its relative newness. It isn’t much different than how our earliest ancestors reacted to the discovery of fire. That new technology had great benefits and advanced progress in many areas of human life. But fire also brought new dangers and uses that might not have been anticipated.

The best way to cut through the current hype and misinformation around AI is to stay informed. Learn from other genealogists how they are using artificial intelligence to improve their genealogy research. Stay up to date on how companies like Ancestry.com and MyHeritage are incorporating AI.

Whether you decide to take a full plunge or just dip your toe in the AI pond, you’ll discover amazing possibilities and ways to take your search for your roots to the next level.