Family historians write stories to forge connections with their roots, as well as to help readers imagine knowing their ancestors. But readers can only walk in the characters’ proverbial shoes when they envision the road they walked upon.

The setting of your stories can function as a time-travel device. Vivid descriptions of the places your ancestors lived, worked, fought and visited enable readers to understand your “characters” of the past. Accurate, complex context about a place transports readers out of their 21st-century mindset and into the world of the story—the world of your ancestors.

Establishing a setting entails more than simply naming the town and the date. For the setting to provide context for your characters’ actions, it needs to be meaningful and relatable to readers.

In this article, I’ll discuss why places can play such a powerful role in your family stories—and how you can research them.

The Importance of Context in Stories

Stories don’t take place just anywhere. They’re rooted in a specific time and place, and are affected by that place’s historical, economic, social and cultural context. Those factors affect not just the characters, but also how the plot unfolds.

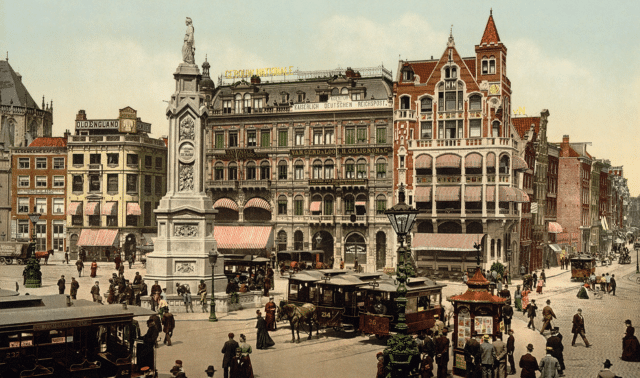

Your words—supplemented by historical and/or family photographs, when possible—spark the readers’ curiosity. They will help your reader better understand the when and where of a story, and emotionally identify with its characters and themes.

In other words, well-written settings can engage hearts, minds and imaginations. Descriptive language and sensory details evoke the sights, sounds, smells and textures of that place at that time.

When the location is known to family members, settings can also remind readers of their own attachment to that place. The image above is of the front yard of my mother’s childhood home. By describing the massive oak tree that shaded years of family gatherings (and the warmth and smell of the wood stove inside), I tap into nostalgia for my relatives. That helps my readers connect emotionally to the story.

However, avoid overly long “dissertations” about a locale. Choose only the details that make the story more vivid, memorable and impactful; you should only sparingly zoom out to the wider historical context.

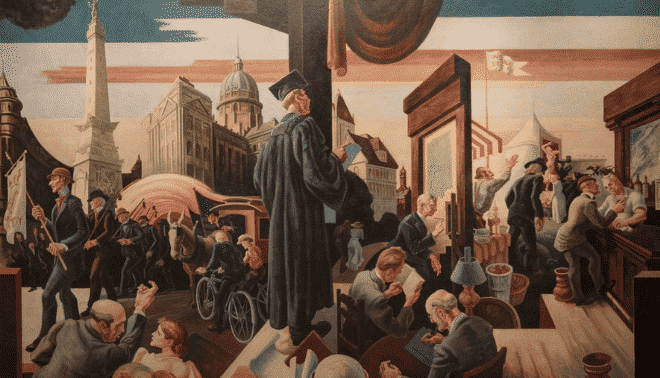

Some settings are widely known to readers, either first-hand or by learning history in school. Many Americans have heard stories about the Great Depression from their elders, for example, but younger generations may only know about the Depression from textbooks.

Different generations and culture will have different benchmarks regarding historic events and time periods. For example, a setting like 1930s Dodge City, Kan., will be familiar to those who grew up watching Westerns. But younger generations won’t have the same associations. Keep a wider audience in mind when describing settings, especially when relying on existing tropes.

Avoid using stereotypes when developing a story in a widely-known setting. Instead, focus on an individual character’s perspective. A family in a bustling city, for example, experienced the Depression differently than one on a farm in a warm climate. What specific hardships did your ancestor endure?

Narrowing the scope of your location can also help your reader better understand the factual historical events being depicted. Settings should reflect just a slice of history—a fairly specific chapter in time—to be effective.

For example, “Colonial Virginia” is very broad, as it could refer to any of the nearly 170 years between the founding of Jamestown and the American Revolution. Characters in that time period would have massively different experiences based on when the story takes place. Was the settlement a remote outpost, or a busy port? Were the characters bound in slavery or servitude, or upwardly mobile gentlemen?

Using Settings to Enhance Character

Writers need to think about both the setting and the characters who live, work and play there. Ask yourself questions like these, which will spur on your research:

- How does your character feel about the setting? Is he a proud, active member of the community, or does he conflict with its traditions and values?

- Does the character struggle against the setting? For example: eking out a living on the frontier, surviving hazardous weather conditions, or facing discrimination or ostracization from local residents.

- Is the land itself a source of conflict?

- Does the place define the rhythms of your ancestors’ lives?

- Does one industry or way of life dominate the place—fishing, millwork, etc.?

Family records and traditions can suggest how your ancestor felt about his setting. That insight, in turn, can help you develop the story’s conflict. Perhaps your great-great-grandfather felt trapped in the countryside and longed for the bustle of a big city. Or a musician took over the family farm rather than follow his dream.

Settings sometimes define characters, rather than the other way around. For example, the ethnic Germans who settled along Russia’s Volga River faced “Russification” in the late 19th century. Their geography largely defined their existence: their proximity to the czar; the flat, riverside terrain that made it ease for Russian forces to enforce his wishes; their distance from ethnic relatives; and their farming way of life reliant on land.

In a more-personal example: My grandmother wrote about how she and her grandfather rescued a buck rather than harvesting his rack as a trophy. In her description, she mentioned the dilapidated state of her grandparents’ house (a sagging roof and broken porch steps). Those details underscored her grandfather’s economic hardship, as well as his kindness—he was willing to forego an economic opportunity to treat the deer with dignity.

Studying Local Histories

To better portray your setting, immerse yourself in that place’s history. The more you know about the historical context there, the better you can appreciate and understand your ancestors’ actions—and convey that to readers.

For most, this means research. But it’s the fun, deep-dive type of research that’s particularly rewarding for family historians. Here are some important sources for studying places:

- The FamilySearch Research Wiki has pages for individual regions, counties and cities.

- Historical and genealogical societies specializing in cultural or national groups offer a wealth of information through their websites and (often) Facebook pages.

- Newspapers and city directories will give you a feel for the place. Look through biographical sketches and advertisements. Did the furniture maker also offer coffins? Did many local companies bear the same family name?

- Maps of various kinds—Sanborn fire insurance maps, plat maps, land surveys and atlases—depict the streets your ancestors traveled.

- Libraries and archives may have special local collections not available elsewhere.

- Published local histories were curated specifically to chronicle the annals of a place.

- JSTOR has many academic articles, including about places and time periods (e.g., “women in the California Gold Rush”).

- Books such as Writer’s Digest’s series of The Writer’s Guide to Everyday Life books can convey the rhythms and minutiae of life in historical places.

You may not use all the information you uncover, but that understanding will still shape how you approach your story.

Consider questions such as the following:

- What made the location unique?

- What were the push and pull factors that brought people to the area or caused them to seek other homes? (Or: What encouraged them to stay as others were leaving?)

- Were there local or regional events that shaped the community?

For instance, my maternal ancestors came to Lunenburg County, Virginia, in 1745. Despite a long history of settlement, Lunenburg County remains sparsely populated to this day (with fewer than 12,000 inhabitants as of the 2020 census). I was the first one in my direct line to be born outside of the county; why didn’t my ancestors relocate despite impoverished circumstances?

Ideally, you could travel to your ancestral homeland yourself. But many people will have to simply imagine the land: the severity or abundance of its climate, the local floral and fauna, how it relates to nearby landmarks and geological features (mountains, rivers, etc.), and what’s changed since your ancestors’ time.

You can virtually “walk” some places using Google Street View. You can also tap tech tools to give you more information about a place—for example, to calculate the distance between two locations and hypothesize whether travel was feasible on foot or on horseback. Historical photos (those taken by your ancestors as well as by others) can also provide information.

Balancing Accuracy and Creativity

Fiction writers have a distinct advantage over nonfiction storytellers: If they don’t know something, they can make it up.

That might make research-minded genealogists uncomfortable. But family historians can educate themselves and their readers about what would have been normal for the setting, even if you take some creative liberties with details. You may not know the exact windspeed over a hill on a particular day in 1865, but research can reveal what would have been typical for your location during that season.

Similarly, historical or family photos might show you typical clothing for the time and place. (“If Joseph was like most farmers in Lunenburg County, he would have worn….”) Of course, you always want to disclose what’s fact and what’s speculation—perhaps in a foreword or author’s note.

Another factor to consider is how much detail to include in your piece. The trick is to engage readers in a setting without overstimulating them with too much information. It may seem counterintuitive, but imaginations actually need a little room to take off on their own. You can reveal the setting as the story unfolds—you don’t need to detail every aspect of a place right at the story’s beginning.

Focusing on a specific time frame can help, making it easier for you to convey small bites of historical information to readers. When they’re inundated with hard-to-digest facts and exposition, readers might be drawn out of the narrative.

Consider Jeannette Walls’ first line in her book, Half Broke Horses: A True-life Novel: “Those old cows knew trouble was coming before we did.” In a few words, she foreshadows the conflict and hooks readers. But she suggests—in a single, plainspoken sentence, without outright telling—the setting. The reader is passively encouraged to think of a small farm, with swaybacked cows wandering aimlessly in a pasture. It’s not a highfalutin place.

Writing Vivid Place Descriptions

Effective writing paints a picture for the reader, capturing the imagination. Choose strong, active verbs and concrete adjectives to keep your readers engaged.

For instance, instead of writing “The roof was damaged by the storm,” play with specific details that help visualize the action. “The wind ripped shingles from the roof” or “Shingles flew as the wind pounded the house” better convey the storm’s power. Figurative language can be helpful, too: “The mighty fallen oak took the gutters down with it, as if clinging to them in a last-ditch effort to stay upright.”

Editing can help you punch up your language. Even best-selling authors have to rework their first drafts to make them shine. Be on guard for overwriting—providing too much detail—and instead focus on only the most vivid details, especially if you need to cut your word count.

Exploring and depicting your ancestors’ physical and emotional landscapes provides insight into your forebears’ lives—and history itself. As you share your family through stories, experiment with the power of place to help bring them alive for your readers.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the November/December 2024 issue of Family Tree Magazine.