Many beginning genealogists are advised to be aware of the mistake called “the name’s the same.” That phrase refers to finding someone in a source—perhaps a census or tax record—and assuming they’re the person of interest simply because they have the same name.

But that’s not always the case, as many people (even within one community) could have the same name. This creates a problem of identity.

If you’ve also found people early in your research who you thought were relatives but later discovered they weren’t, you know the disappointment. You might feel you’ve wasted your time, or even resist letting go of these phantom ancestors if you’ve spent long hours in the search.

But don’t despair. We can learn the skills and strategies to properly solve problems of identity in our research.

Here are different factors to consider when establishing someone’s identity, plus a case study for how I was able to sort through a many-named research subject.

What Is Identity in Genealogy?

Genealogical research usually begins with a question we want to answer. That research question keeps our focus on the sources most likely to contain the information we need and helps us use our time efficiently.

Genealogists typically have research questions that fit into one of three broad categories:

- Relationship: Is X related to Y? For example: Is Thomas the father of James?

- Event or circumstance: When and where did X do Z? For example: When did Thomas immigrate and what port did he arrive in?

- Identity: Are these two the same person? For example: Is this “James Tanner,” in Woodford County, Kentucky, in 1850, the same person as my ancestor, James Tanner?

That third type of question is our focus. Genealogy Standards by the Board for Certification of Genealogists describes identity as: “Characteristics and contexts distinguishing one person from all other people throughout history.”

This definition gets right to the beautiful point: We are all unique in time and place, and so were our ancestors. Through our research, we search for evidence of what made our ancestors one-of-a-kind.

How do we do that? By looking for defining attributes or characteristics, what I call “identity markers.” These describe aspects of our ancestors, and (other than name) include:

- Birthdate/birthplace

- Occupation

- Location (or residence)

- Religious affiliation (or lack thereof)

- Middle name

- Nickname

- Landownership (or lack thereof)

- Military service (or lack thereof)

- Literacy (or lack thereof)

- Handwriting

- Place of death/burial

We use markers like these alongside other experiences and relationships that we’ve identified, forming the basis of “cluster research” or “F.A.N. [friends, associates and neighbors] research.”

If we can weave together enough identity markers, relationships and experiences from the sources, we can arrive at the unique person in time and place.

Common Mistakes With Identity

There are two major categories of identity mistakes we encounter in genealogical research.

The first is merging identities when sources that actually describe different people are believed to describe one person. For example, two males named Levi Prather lived in the first district of Montgomery County, Maryland, in 1870. One was a 3-year-old living with his presumed parents, and one was a 30-year-old man living with his presumed wife. The two Levis had different ages and living arrangements, but could be mistaken for one man.

In a similar way, the other major identity mistake is splitting identities when sources seem to refer to several different people but actually refer instead to one. For example, a man named Joe Doran appeared in several Hardin County, Tennessee, sources. A man named Felix Doran appeared in other sources. For many years, I believed they were two different men when in fact they were one man.

Both types of issues stem from a lack of thorough research and analysis. Certain assumptions—such as the belief that an ancestral couple was married—are always operating in the background, torpedoing our research by giving us blind spots.

In other cases, our research is simply too shallow. Perhaps we’ve overly relied on records that are available online, missing out on other resources. (There are still many records that haven’t been digitized.) Online databases also operate via name-search, making identity mistakes easier to commit.

And, of course, individual records can contain incorrect or conflicting information, or details that are too ambiguous to understand without the right context. In the earlier Joe/Felix Doran example, I didn’t have one single piece of evidence that suggested the names both referred to him. I only came to that conclusion by looking at all the evidence at once.

6 Ways to Accurately Prove Identity

It’s important to recognize and work against these pitfalls. When we don’t prove identity sufficiently, we’ll inaccurately attach our ancestors to other families. None of us want to do that!

Here are six ways prevent identity mistakes:

1. Create a research plan.

The research question we discussed earlier should result in a dedicated research plan. Determine what and where you’re going to search ahead of time, and consider seeking records that haven’t yet come online.

2. Track progress and identity markers.

Whether you use an Excel spreadsheet, a Microsoft Word table or a genealogy software program, document what you’ve done. Make special notes about any identity markers you come across—for example, a middle initial in a census or tax record or a “mark” instead of a signature in a deed or marriage record.

3. Pay attention to chronology.

Finding new records can be a rush, so many genealogists spend most of their time looking for them. But pause to consider whether it’s plausible for one person to appear in the various documents you’re finding. For example, it’s unlikely one person would be listed multiple times in the same source. Therefore, multiple listings of similar names likely refer to different people.

Also consider life context when analyzing records: Most people didn’t marry for the first time or have their first child at age 50, so a record suggesting they did might well refer to someone else.

4. Place individuals in the correct family.

Think of your ancestor as part of a family unit, which can help you distinguish them from others of the same name. Note their parents, spouse(s), children and siblings, and use those facts to eliminate candidates who have the same name but different relatives.

5. Use tables and timelines.

Extract details from records and organize them in a new way to look for patterns. Compare details about two same-named people in a table to reveal whether it’s likely they’re the same person, or build a timeline to keep tabs on multiple sources and events.

6. Find and utilize maps.

Sometimes we can discern different individuals by visualizing where they lived. Many of the maps we need are not available from websites such as Ancestry and FamilySearch. Look for them instead at state or university archives, historical societies, the Library of Congress or resources like the David Rumsey Map Collection. In addition to censuses and maps, deeds and tax records can help pinpoint our ancestor’s location.

Case Study: Finding Matilda

Let’s look at a case study from my own research to see identity issues in action.

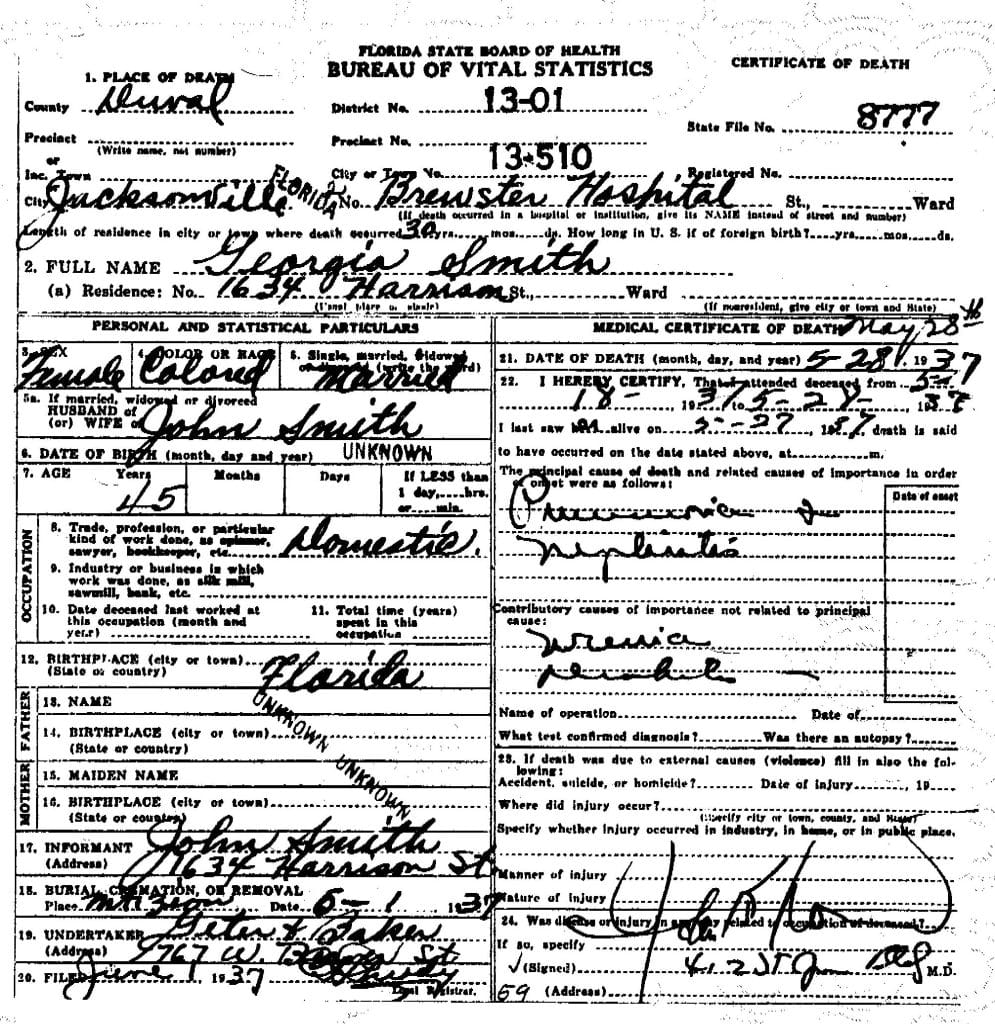

My goal was to uncover the maternal ancestry of Georgia Harris, who lived in Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida. Georgia was married to John Smith from 1920 until her death in 1949. Her death certificate lists John as the informant but (unfortunately) did not provide information about her parents.

My grandmother’s family Bible, however, reported Georgia’s mother was named Matilda Vickers. A Matilda Vickers died in 1944 in Jacksonville, with a John Smith acting as informant on her death certificate. Her birthplace was Taylor County, Florida, with an unnamed father and a mother named “Viney Nealy.” (I couldn’t find Viney Nealy in any Taylor County record.)

My search for Georgia’s mother crossed two states and multiple counties—and served as a reminder why it’s so important to consider identity when pursuing research.

A Different County

Unknown to some descendants, Georgia was previously married to Isaac Garner in Madison County, Florida. A search for records in that county revealed additional possibilities.

In the 1900 census, Georgia’s apparent mother (“Matilda Davis”) lived near her and her sister Ruth in Madison County. Georgia and Ruth are listed as step-daughters to Matilda’s husband, Perry Davis.

I found Matilda and Perry’s marriage record for 22 April 1899, in which Matilda is listed as “Tilda Harris.” Was my grandmother’s Bible wrong about Matilda’s maiden name?

A Different State

I turned my attention to Matilda’s other daughter, Ruth. Ruth married Nish Torrence and migrated to Philadelphia. By the 1920 census, their household included three children and a Florida-born woman named Matilda Garvin. Matilda’s relationship to Nish was reported as mother.

Who was this Matilda? Was she actually Ruth’s mother, or was Matilda also the name of Ruth’s mother-in-law? Searches for Matilda Garvin in Philadelphia city directories turned up nothing, nor could I find a marriage record between Matilda Davis and a man named Garvin.

Ruth died in 1924 in Philadelphia. Her death certificate might have provided her mother’s maiden name and the name of her then-unknown father, but it was (at the time) under privacy restrictions.

By the 1930 census, Nish Torrence was remarried and lived in Camden County, New Jersey—without Matilda Garvin. I couldn’t find evidence that a Matilda Garvin died in Pennsylvania or New Jersey. Like so many of our ancestors, this Matilda seemed to magically appear in one record, only to disappear in others.

Later Censuses

I searched for more clues about a possible Matilda Vickers back in Jacksonville. I already had her death certificate, but that hadn’t led anywhere useful to my research goal.

In the 1930 census, a Matilda Vickers lived with a woman named Katie Middleton. But Jacksonville city directories in 1928, 1930 and 1931 all list her as living at the home of John and Georgia Smith. The 1928 directory refers to her as the widow of a Peter.

The 1935 state and 1940 federal censuses both listed Matilda as living with a man named Cornelius Garner, who was called a roomer. Looking over all these different surnames and residences, I felt no closer to solving this puzzle.

But by this time, Ruth Torrence’s 1924 death certificate had appeared in an Ancestry collection. Her husband, Nish, was the informant and reported her parents as Peter Harris and Matilda Mealy. Could this be the Peter referred to in the 1928 city directory? This was the first source to assert a father for Ruth (and presumably Georgia).

Searches of Duval and Madison County records for Pete(r) Harris came up empty, and I couldn’t find a marriage record for a Matilda Mealy.

Making a Timeline

Who were all these Matildas? I decided to place every source I’d found for the various women named Matilda into a timeline (see below). I added all the identity markers I had gathered into a Notes column.

| Date | Location | Source/event | Name in record | Estimated age/birthdate | Identity marker notes |

| 1 June 1880 | Taylor County, Fla. | 1880 federal census | Matilda Nealy | age 8 (b. 1872) | – Lived in Perry, 1st electoral district – Attending school |

| 3 August 1891 | Hamilton County, Fla. | Marriage record to Peter Harris | Matilda Nealy -> Matilda Harris | n/a | None |

| 24 April 1899 | Madison County, Fla. | Marriage certificate to Perry Davis | Matilda Harris -> Matilda Davis | n/a | None |

| 1 June 1900 | Madison County, Fla. | 1900 federal census | Matilda Davis | age 26 (b. March 1874) | – Cannot read or write – Birthed two children; two still living – No occupation – Renting home – Lived in Withlacoochie, 8th precinct |

| 17 August 1916 | Duval County, Fla. | Marriage register to Frank Garvin | Matilda Davis -> Matilda Garvin | age 41 (b. 1875) | None |

| 1 January 1920 | Philadelphia, Pa. | 1920 federal census | Matilda Garvin | age 42 | – Can read and write – No occupation – Widowed |

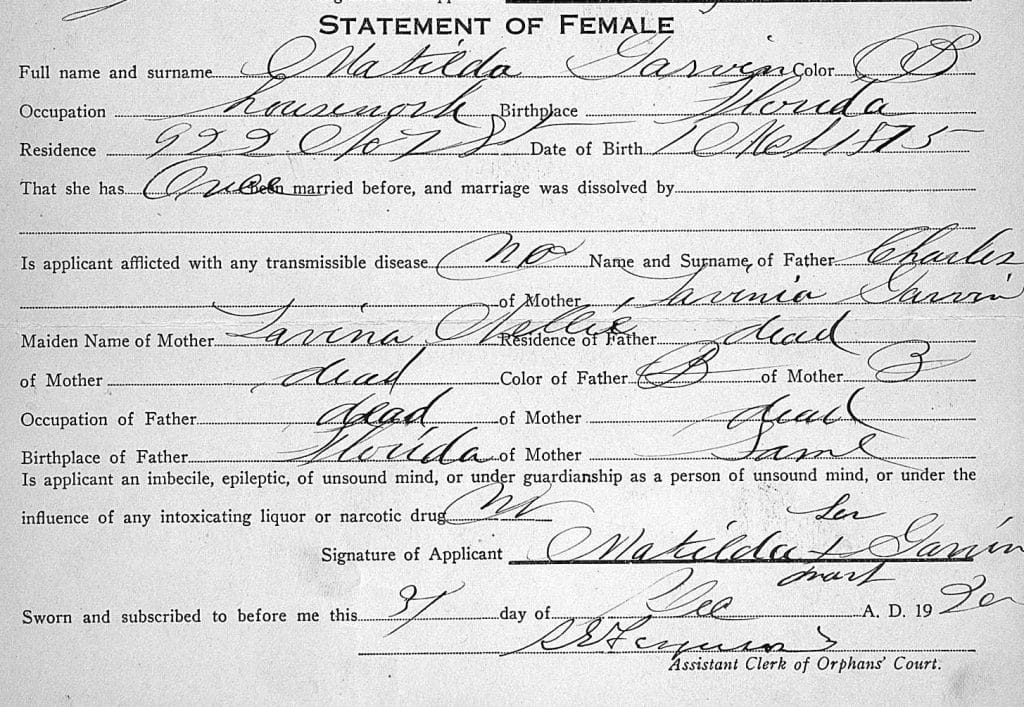

| 1921 | Philadelphia, Pa. | Marriage application and return to Peter Vickers | Matilda Garvin -> Matilda Vickers | 1 March 1875 | – Parents: Charles and Lavinia Nellie (deceased) – Married once prior – Signed with mark |

| 1 April 1930 | Duval County, Fla. | 1930 federal census | Matilda Vickers | age 55 (b. 1875) | – Living with Katie Middleton, called a cousin – No occupation |

| 3 July 1944 | Duval County, Fla. | Death certificate | Matilda Vickers | age 70 | – Informant: John Smith – Birthplace: Taylor County, Fla. – Mother: “Viney Nealy” (Father unknown) – Burial at Mt. Zion Cemetery |

And there it was: The timeline starkly revealed that there was no overlap between the sources that named Matilda Davis, Matilda Garvin and Matilda Vickers. I had thought I was dealing with at least two (and possibly three) different women. But the timeline helped me see that these sources could describe one woman who married and was widowed multiple times.

By spending more time analyzing the records, I finally unlocked Matilda’s identity. I could only overcome the numerous inaccuracies in individual sources by looking at them together:

1891: Matilda Nealy (not “Mealy”) married Peter Harris in Hamilton County, Florida. The original marriage record misspelled her first name as “Matida” (no letter “l”). Hamilton County neighbors Madison and Taylor counties.

1899: Matilda, presumably widowed, married Perry Davis in Madison County.

1916: Matilda went to Jacksonville where her daughter Georgia lived. Widowed again, she married Frank Garvin. The original marriage register recorded the name Frank Gowen instead of the accurate surname of Garvin. Frank Garvin died in Jacksonville in 1918.

c. 1920: Matilda Garvin moved to Philadelphia before the 1920 census to live with her daughter, Ruth Torrence. While in Philadelphia, Matilda Garvin married Peter Vickers in 1921. Ruth died in 1924, and Peter in 1925.

c. 1930: Matilda moved back to Jacksonville. In the 1935 and 1940 censuses, she lived with a Cornelius Garner. He is Georgia’s son from her first marriage, but is never correctly identified as Matilda’s grandson.

1944: As we’ve discussed, Matilda died in 1944 in Jacksonville.

A Family Reunited

Only one document—the Pennsylvania marriage application of Matilda to her fourth husband, Peter Vickers—included the names of her parents: Charles and Lavinia Nealy. In that same application, Matilda said she had been married only once prior.

That information allowed me to finally place Matilda Nealy accurately in her birth family. I found her in an 1880 census entry in Taylor County. By then, Lavinia had died, and Charles re-married to a Netty Williams in 1878. (The name “Viney Nealy” reported in Matilda’s death certificate was accurate; “Viney” is a nickname for Lavinia!)

Matilda married four times in four different locations, and only appeared in the census with one husband. But certain identity markers stayed the same: Matilda was an African American woman, impoverished and illiterate, and her movements shadowed her familial relationships. Her birthdate (except for one source) also was remarkably stable. By looking at all the records in concert with each other, I was able to connect the dots of her life.

A name is never enough to prove identity. Fortunately, genealogy has standards that can help us understand and avoid the identity minefield waiting for us in records. By adding and analyzing identity markers as we find them, we can solve difficult identity problems.

We’re never going to have all the pieces we’d like to solve our family mysteries. But we can gather enough to solve the puzzle.

A version of this article appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine.