Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

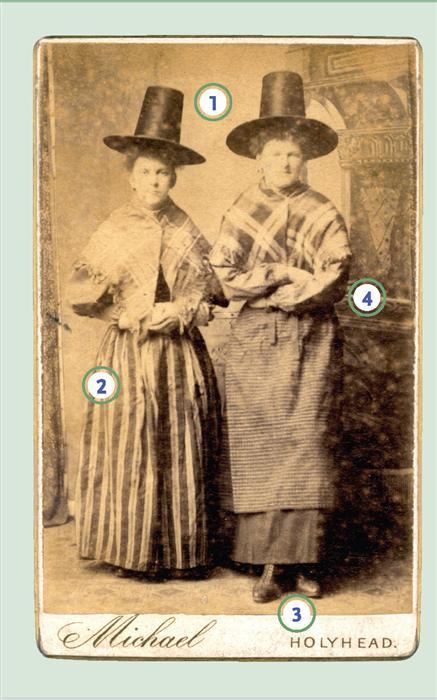

If you have a family photograph of people in unfamiliar attire — such as the outfits on these two women — you might wonder “What in the world?” Instead, ask “Where in the world?” That photo could show your immigrant ancestors dressed in clothing common in their homeland.

Fortunately, you needn’t make a trans-Atlantic voyage to figure out the origins of a foreign photograph. Finding your family’s homeland based on a picture is easier and cheaper than buying a travel package on Orbitz. The same clues that helped me sort out this photo mystery can lead to breakthroughs in your own immigrant ancestry.

Fashion fiction

First, let’s clear up a myth regarding immigrant forebears: People from other countries didn’t always wear ethnic-looking “folk” costumes like those on the women here. Your ancestors’ everyday clothing depended on their country of origin and whether they lived in a city or the countryside. Urban dwellers often wore the same fashions popular throughout Europe and the United States. For instance, in the 1890s, the leg-o-mutton sleeve (a puffy shoulder tapered to a narrow forearm) showed up on Western-style dresses in Copenhagen, Paris, Rome and Ankara, Turkey. In rural areas, attire was usually a mix that depended on cultural identity, economic status and lifestyle. Women occasionally accented everyday clothes with ethnic headgear, such as the beaver hats shown here.

Outfit origins

Unusual clothing requires a special costume guide. Check libraries for Auguste Racinet’s The Complete Costume History, first published in 1888 (reprinted in 2003 by Taschen). It covers the entire history of costume, most of which predates photography, but the final chapter is a genealogical gem full of color plates illustrating traditional fashions up to 1800.

A smaller book, Robert Harrold’s Folk Costumes of the World (Sterling), describes the history of Welsh dress, which became a symbol of national identity. Today, ladies might wear outfits like those shown here for occasions such as St. David’s Day, which honors the patron saint of Wales.

This 19th-century photo is sepia tone, but Harrold’s illustrations let you imagine the clothing in full color. A typical late-1800s or early-1900s Welsh costume consisted of a tall black beaver hat with a white frilled bonnet, a white blouse with red trim at the cuffs, a bright red underskirt, a checked apron and a shawl. These women aren’t wearing bonnets, white blouses or folded-back skirts, but one sports a checked apron and both have shawls and hats. According to the Welsh National Costume Web site <www.welsh-costume.co.uk>, women started wearing these hats — based on the men’s top hats popular from 1790 to 1820 — during the 19th century. The longevity of this style of dress doesn’t do much to narrow the photo’s date.

Informative imprints

Ideally, your picture will bear a photographer’s imprint, which provides the studio name and, often, its location. Then you can research the locale — in this case, Holyhead — using gazetteers. The 1884 Gazetteer of the World (Lippincott) tells me Holyhead was an island off the coast of Wales (it’s now called Holy Island), home to a town of the same name. I also found out the closest port is Dublin, which was under British rule during the 19th century. This last bit of information would come in handy when searching for a point of emigration.

Pay attention to the style of the photographer’s imprint — whether it’s printed, script or part of a decorative logo. This 2½×4-inch gilt-edged beveled card has the photographer’s name in script, common in the mid-1880s.

If your photo lacks a photographer’s name and you’re not sure where the subjects came from, try browsing costume books for clothing similar to what’s in your picture. You also can compare your photos to the images of immigrants in native dress in Augustus F. Sherman: Ellis Island Portraits 1905-1920 (Aperture). For descriptions of props and backdrops, such as the painted one in this photo, see Linda Setnik’s Victorian Costume for Ladies 1860-1900 (Schiffer). The next time you see a foreign image, instead of wondering “What in the world?” you can say “Aha!” And if you can make that trans-Atlantic voyage after all, plan a trip to your ancestral homeland and check out a few genealogical documents while you’re there. Don’t forget to take a copy of the picture in case you meet some long-lost relatives.

From the February 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT