Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

The end of the Civil War—or the “late unpleasantness,” as polite Southern society referred to it—saw the South in shambles. Nearly half of Confederate soldiers were killed, wounded, captured or missing. Businesses were disrupted by war and many assets were destroyed by Union forces. An unjust, but deeply entrenched, social order was partially overturned but not yet replaced.

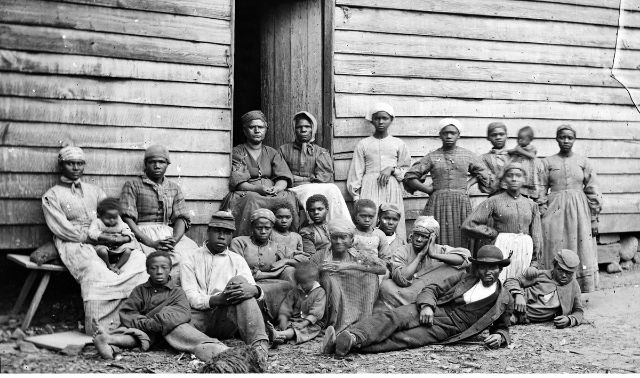

Across the South, millions of African-Americans suddenly had freedom, but few resources. Many were stranded without family, friends or property. Business owners lost livelihoods and lifestyles that relied on unpaid labor. Black and white workers competed in an uncertain, often hostile job market that itself was going through hard times.

The bottom line is that whether black or white, wealthy or without means, your ancestors in former slaveholding states likely experienced some turbulent times. This upheaval may be reflected in the records you’re searching. Your ancestor may seem “gone with the wind”—either entirely missing or found inexplicably in an unfamiliar location. This guide will help you locate resources to find your Southern ancestors after the Civil War.

ADVERTISEMENT

How the wind blew

The end of the Civil War didn’t cause a whirlwind of sudden, enormous outmigration from the defeated South. The pressure on Southerners was more like a slow but persistent breeze that gradually grew stronger. For the first several years postwar, poverty, a sluggish economy and land ownership pinned many to their homes. Some former slaveholders made labor contracts with former slaves, preserving a status quo of sorts. Meanwhile, the civil rights efforts of Reconstruction caused modest, if temporary, gains in black civil rights.

During this time, Southern migration was mostly an internally rotating system. Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas and Tennessee lost a lot of black residents. Texas, Florida, Georgia and North Carolina saw population surges, especially in cities, where destitute farm workers came to start over.

Some Southerners left the South during Reconstruction. Cheap land, made available by the Homestead Act of 1862, began drawing folks west. So did Western and Midwestern mining towns, logging camps, railroads and other industrial meccas, though initial demand was mostly for white men. Others flung themselves further away to places including Brazil and Liberia.

ADVERTISEMENT

When Reconstruction and the Freedman’s Bureau ended their efforts by the 1870s, the South became a much worse place for African-Americans to live. New laws restricted freedom, entrenched discrimination and even forcibly indentured the poor and unemployed. Meanwhile, the South’s economy hadn’t risen from the ashes. By the early 1900s, the enormous gusts of the Great Migration began blowing millions of Southerners to Northern industrial cities.

Several types of records can help you find missing or migrating Southern ancestors during the decades after the Civil War. Most of these records aren’t as segregated as you might think: They’re not just for blacks or whites, Southern or Northern sympathizers, the haves or the have-nots. So keep an open mind while researching in the following records.

Military records

Thousands of Confederate soldiers never came home. They were dead or too wounded to travel, or decided not to return. Sources listing deaths include the 14-volume series Deaths of Confederate Soldiers in Confederate Hospitals and the 28-volume Confederate Burials, both by Raymond W. Watkins.

For those who survived the war, records may offer clues about where the soldier and/or his family ended up or (if you’re working backward in time) where they lived before the war. As you approach military research, don’t assume that all Southerners fought for the South or that every Confederate soldier was white. Every state mustered at least one Union unit (the four from South Carolina were all US Colored Troops). Some Confederate soldiers switched sides, especially while prisoners of war. A few free blacks served the Confederate cause, and many enslaved blacks were forced to serve the Confederacy alongside or without their owners.

Start your research by first confirming your ancestor’s military service. Begin with the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database of all known soldiers from Union and Confederate forces. Another source is the Veterans Schedules of the 1890 US census, which enumerated surviving Union soldiers but included some Confederates, too. Only schedules for half of Kentucky and states alphabetically following survive; search them at FamilySearch.org or Ancestry.com.

Next, use what you’ve learned to find compiled service records and records related to your ancestor’s service. Find digitized service records for both sides, as well as muster rolls, prison and hospital registers and more, on Fold3.com. You also can order compiled service records from the National Archives.

The federal government didn’t pay out pensions to Confederate veterans or their families, but many Southern states did. Start your search for Confederate pensions at state archives (a veteran could apply in his Confederate state of residence, even if he served from another state), or check the FamilySearch online catalog for microfilmed records (search by state, then look under Military Records, Civil War, Pensions). You can rent film to view at your local FamilySearch Center. FamilySearch.org also has digitized Confederate pension records for Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina and Tennessee. These records aren’t yet indexed, which means you’ll need to browse them as you would microfilm reels, but your patience browsing them could pay off. Pension records can be especially helpful for tracking down later residences of veterans and information about their widows and children.

A variety of other military-related resources may be available, too, depending on where your ancestor served. For example, you may find Confederate burial records, biographies of local war heroes, or even unique record sets like the 1864 Georgia census of white males (ages 16-60), taken to reorganize the state militia. You can search this census on Ancestry.com and browse it in the Georgia Archives Virtual Vault.

In military records, look for clues to help you find the soldier or family—or to help you recognize them if they pop up in unexpected places. Clues include name spelling variations, residences, relatives’ names and residences, evidence of imprisonment or hospitalization, discharge date and place, and death date and place (which is often the burial place).

Reconstruction records

The federal government occupied and oversaw Southern life during the post-war period known as Reconstruction. During and beyond that time, families, towns and entire states rebuilt their financial foundations. Relations with the North began to be mended. Initial progress was made toward basic civil rights for African-Americans. All of these created records in which ancestors may appear.

Southern Claims Commission records: In 1871, the federal government’s Southern Claims Commission began processing claims for reimbursement of Southern livestock and property taken by Union troops during the war. An estimated 10 percent of Southerners (black and white, rich and poor) appear in testimony or discussion of claims of their neighbors and relatives. You can search a master index to claims on Ancestry.com, as well as some states’ allowed, disallowed or barred claims. Fold3 has comparable data. Original records are at the National Archives.

The Confederate Citizens’ File (1861-1865) named Southerners who supplied goods and services for the Confederate cause, making them ineligible to apply with the Southern Claims Commission for reimbursement of wartime property losses. These records may shed light on ancestors’ circumstances and locations during the war. FamilySearch.org has an index; record images are available by subscription to Fold3.

Confederate pardons: President Andrew Johnson pardoned many Confederates by proclamation; others had to apply for amnesty and take oaths of allegiance. Applications for pardons include the petitioner’s residence, helping you locate an ancestor. Applications from 1865 to 1867 are indexed on FamilySearch.org, with the record images on Fold3 in the Confederate Amnesty Papers collection.

Voting registrations: Federal rules of Reconstruction required that Southern states register black and white voters. Loyalty oaths were part of the qualification process. Some of these registrations and/or signed oaths still exist. Alabama’s (1867) is searchable in an online database at its state archives website). Texas and Georgia (both 1867-1869) are searchable on Ancestry.com. Registrations for Louisiana, Mississippi, North and South Carolina and Virginia are at their respective state archives; some have been filmed or published.

Freedman’s Bank Registers: From 1865 to 1874, the Freedman’s Bank served black clients in major (mostly Southern) US cities. Registers of depositors’ signatures often include birthplaces, residences, former slaveholders’ and/or plantation names, relatives’ names and other clues to where someone lived or came from. Search Freedman’s Bank registers (with images) on Ancestry.com and FamilySearch.org.

Freedmen’s Bureau Records: For seven years after the war, the Bureau of Refugees, Freemen and Abandoned Lands administered relief to the white and black poor and recorded black marriages, labor contracts, indentures (often between black workers and white employers) and more. Major research libraries have microfilmed records. Indexed and digitized records are gradually appearing on FamilySearch.org, organized by state. Records are also on Ancestry.com. The Mapping the Bureau website can help you find Freedman’s Bank and Freedmen’s Bureau records of field offices all over the South.

Censuses

Federal censuses taken in 1870 and 1880 may find your relative in their new places of residence. You can search these censuses on Ancestry.com, MyHeritage and Findmypast.com, and free at FamilySearch.org (FamilySearch’s 1880 census links to record images on Ancestry.com, where they’re free, although registration is required to view them). The 1890 census was almost entirely destroyed after a fire in the building where they were stored, but you can view the remaining fragments at the sites mentioned above.

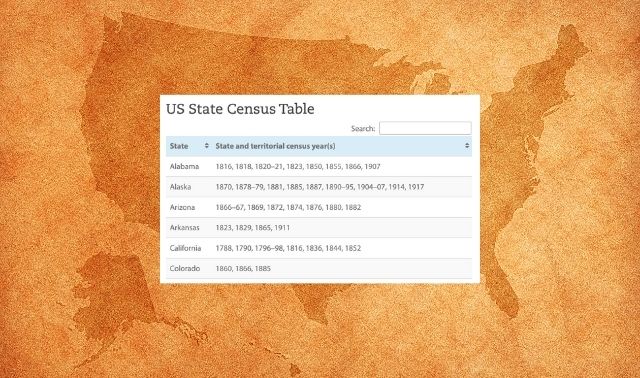

Several Southern state censuses were taken during this time period, and the few surviving ones can help you pinpoint your ancestors’ whereabouts:

- An 1866 Alabama census is indexed on FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com.

- An 1876 Missouri census for several counties is on Ancestry.com.

- South Carolina’s 1868 agricultural census and 1869 population census are fairly complete and include birthplace and prior residence. Look for the 1869 census on microfilm through FamilySearch and the 1868 agricultural census at the South Carolina state archives.

A handful of states, including Colorado, Nebraska and New Mexico, took censuses in 1885. Some, such as New York, took censuses during years ending in five throughout the second half of the 1800s. Find these digitized on FamilySearch.org: Filter by place or type census in the Filter By Collection Name box. Look for other state census records enumerating individual counties by searching online for the name of the county and state, the word census and a date range (in Google searches, use this format: 1865..1880).

Land and tax records

Even if your relatives disappeared, their property didn’t. If they owned land, you may be able to trace its ownership forward or backward. You also may find ancestral lands and personal property assessed in tax records. These documents often hold clues about when, where and even why families moved.

First, try to determine whether an ancestor owned land. In his or her entry in the 1860 and/or 1870 federal census, does the column labeled “value of real estate owned” have a number there? (Value of personal property is requested in another column; that generally meant portable property and in 1860, included slaves.)

State or local tax records can give you a year-by-year accounting of your ancestor’s property ownership. You may find someone’s real estate tax dropping dramatically one year or a landowner disappearing altogether, indicating you should look for a land sale or disposal around that time in county deed records. When a landowner died, tax records might continue to list him or her (often with the word heirs or hrs) while the estate was in probate, sometimes for many years. In that case, your next stop would be county probate files.

Some state and local tax records have been digitized and are increasingly available online. For example, a large collection of digitized Texas county tax rolls (1846-1910) is on FamilySearch. Also, direct federal taxes were levied from 1861 to 1872 (only enforced in areas under federal control during the war). Ancestry.com has a lot of these covering the 1860s (many are also available on microfilm). In addition, FamilySearch has digitized the 1865 tax on Louisianans (look for it in the digitized FamilySearch Books collection).

Start your search for tax records at state or regional archives or libraries, or at county offices. To find records FamilySearch has microfilmed, search its online catalog for both the state and county, and look under Taxation. WorldCat will help you find microfilmed records in many libraries, but keyword searches by location and dates with taxes will yield a lot of irrelevant results. If you know exactly what year(s) and locations you’re looking for, WorldCat is an excellent place to search for collections held at repositories other than the Family History Library.

Armed with what you learn about land ownership from census and tax records, search county deed indexes of both buyers (grantees) and sellers (grantors) for the landowner’s name. This research can be time-consuming and often has to be done in person. But it can be worth it: Deeds may give a buyer’s or seller’s current residence, as well as the names, relationships and residences of other relatives involved in the transaction (such as heirs or co-owners). You may find a death date in deeds disposing of a deceased person’s land.

Deeds weren’t always recorded immediately—or sometimes, at all. Review the indexes for several years before and after you think your ancestor owned land. If you don’t find a deed, look for probate or estate records that might show land transferring to an heir without deed filing. Check deed indexes for other family members who owned land in that area, too (including in-laws). Their land dealings and migrations may contain clues about your closer kin.

Many Southern landowners declared bankruptcy in the years following the Civil War. Search for related land sales in county sheriff’s sales, which may have been announced in the newspaper (try searching for the address). Bankruptcy proceedings, usually among federal district or circuit court records, may divulge more clues about family migrations.

Finally, remember that a lot of farmers didn’t own the land they worked. They were wage laborers, sharecroppers or tenant farmers. Sharecropping or land tenancy contracts may have been filed at county offices, with or without the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau. Search both county court records and Freedmen’s Bureau records for evidence of these contracts. Also look for family papers of the hiring family in regional archival collections. To help you find these, run a keyword search of the WorldCat and ArchiveGridonline catalogs with that family’s surname, county of residence and the word papers or similar terms.

All these records and search strategies may not apply to every post-Civil War Southern ancestor. But chances are pretty good that, with some digging, you’ll find documents pointing like a weather vane in whatever direction the winds of change may have blown them.

Pro Tips

- Civil War conflicts led to the burning of some Southern courthouses and the records inside. The October/November 2013 Family Tree Magazine offers strategies to help you trace ancestors from these “burned counties.”

- Look for migrating groups, not just individuals, if you think your ancestors left the South. Finding several familiar names (including in-laws) clustered in a census column or cemetery plot can confirm that this is your family in an unexpected place.

Toolkit

Websites

- The African-American Migration Experience

- The African-American Mosaic: Colonization

- Ancestry.com

- Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Database

- FamilySearch.org

- Fold3.com

- Freedmen’s Bureau Online

- General Land Office Records

- Mapping the Freedmen’s Bureau

- Confederados

Books

- Courthouse Research for Family Historians by Christine Rose (CR Publications)

- A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your African-American Ancestors by Franklin Carter Smith and Emily Anne Croom (Genealogical Publishing Co.)

- Life in Civil War America by Michael O. Varhola (Family Tree Books)

- The Ordeal of the Reunion: A New History of Reconstruction by Mark Wahlgren Summers (University of North Carolina Press)

- The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America by James Noble Gregory (University of North Carolina Press)

More Online

Free Web Content

75 best state genealogy websites

Timeline of US slavery

Timeline of Southern US history

For Plus Members

10 best Civil War websites

Collecting pensions

Land records guide

Family Tree Shop

The Family Tree Sourcebook eBook

Guide to land records

Reconstruction 101 for African-Americans video class

From the May/June 2015 Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT