From the earliest days of its history, the western US boundary was like a back door left open: a tempting invitation to explore the national backyard. Millions of Americans and immigrants passed through that back door on foot and horseback, in riverboats and wagons and stagecoaches, and eventually by train. Many wanted to homestead a little piece of America. Some sought their fortunes in gold from California or Yukon, or silver from Nevada or Colorado. Still others sought religious havens in the Mormon settlements of Utah or the missions of Oregon Territory.

Whatever propelled your ancestors west, finding them and their stories may start you on your own research adventures. The paper trail may be faint, as government offices, churches, newspapers, schools and businesses were fewer on the frontier. People moved casually from one squatter-settlement or mine to the next. They often traveled light, without a lot of extra paper, and they prioritized survival over the writing of histories. You might lose track of your relatives for years at a time. Or you may find their names suddenly popping up in frontier-related records—such as a federal land purchase—with no idea why they’re there.

Early settlers discovered that for all its hardships, the West often provided valuable resources: land, game, timber and gold. Similarly, if you can get your bearings in the apparent genealogical wilderness of frontier records, you may discover rich veins of information about your pioneer ancestors and their lives in the nation’s backyard. Start your genealogical journey by following these seven tips.

1. Find the Frontier

The American frontier wasn’t just one “wild west” but a range of diverse regions, each with its own cultures and challenges. Distinct groups of American Indians already inhabited almost every area, even if thinly. French and Spanish influence was felt in varying degrees in areas those countries colonized, particularly along the Mississippi River, in Florida and in the Southwest. There were even spheres of British and Russian influence (Oregon Territory and Alaska, respectively).

From the beginning of nationhood to the end of the 1800s, the frontier was also a moving target—an imaginary line marching gradually west until the 1840s, when it stalled at the Mississippi River. Settlers generally saturated all inhabitable land east of this frontier line. A second pattern of settlement began in the 1850s: A hop-skip pattern moved westward over the plains but also eastward from California. Settlers traveled through less-desirable lands to pockets such as Oregon’s Willamette Valley or silver mines in the Rockies.

Chunks of frontier came under US domain at different times and various stages of development. New Orleans was a thriving city of 8,000 when the United States acquired it in 1803, the same year fast-growing Ohio became a state. Another 60 years passed before the sun-baked Arizona desert even became a territory.

Living on the frontier meant access to fewer—but important—tools. The same principle applies to tracing ancestors on the frontier. When you first find an ancestor west of the original 13 Colonies, learn a little history of that area. Were your ancestors there during the region’s colonial days? Did they arrive after US acquisition but before statehood? How developed was the region at the time? If you find an ancestor hanging out in a pre-statehood area or in a remote and underpopulated area, consider them pioneers and search for them accordingly.

2. Search Colonial Sources

If your ancestor lived under a foreign territorial government, try to learn what records may still exist. There may be colonial censuses, land sales, marriage contracts, slave sales, estate documents and more. Successions—also called probate—can be particularly rich in details about a family’s possessions (including slaves) and lines of inheritance.

You can find colonial-era records today at libraries and state archives throughout the West and internationally. The New Mexico State Archive, for example, has early land claims in its Spanish Archives of New Mexico collection, and Florida Memory has digitized Spanish land grants.

Start by consulting Locating Colonial Records of Genealogical Value at the RootsWeb wiki. You’ll find descriptions of the kinds of records that exist, and a detailed summary of Spanish colonial records available by state.

Also look to state and regional genealogy guides, such as our State Guides. Or search genealogical and archival library catalogs: A keyword-search for “French Colonial” in the FamilySearch catalog brings up titles including Early Louisiana Settlers, 1600s-1800s and Arkansas Colonials: A Collection of French and Spanish Records Listing Early Europeans in the Arkansas, 1686-1804.

3. Look to Land Records

As the US government acquired new territories, federal and state offices sold or granted acreage to enrich their coffers and encourage settlement. Uncle Sam has distributed more than a billion acres of public domain lands. Our ancestors acquired government land through two major programs:

• General land sales and grants of public land began in the 1780s, but Congress didn’t see large-volume response until after the 1820 Homestead Act dropped the minimum purchase to 80 acres at $1.25 per acre. Sales surged again, to the tune of 214 million acres, after a similar act in 1862 granted 160 acres to any adult who paid a $15 fee and occupied the land for at least five years. Records of these grants and purchases are in land entry case files, which may include applications, copies of immigrants’ naturalization papers, certificate of entitlement, proofs of homesteading activity and final patents or cancellation paperwork.

You can search images of more than 5 million awarded land patents at the General Land Office Records (GLO) website and in county deed books, usually located at county courthouses. More than 10 million case files, including those for canceled and rejected applications, are at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), along with tract books that document buyers or homesteaders. Finally, some states sold off their own lands. State genealogy guides will direct you to resources such as the Missouri Land Patent Records database at Missouri Digital Heritage and the Texas General Land Office.

• Military bounty lands were awarded as compensation to veterans of wars from the Revolution through the Mexican War. The US government paid nearly 70 million acres of land. In addition, Georgia, Maryland, Massachusetts (along with Maine), New York, North and South Carolina, Pennsylvania and Virginia offered their own bounty lands, often west of their current boundaries. Connecticut awarded “firelands” in its Western Reserve, now in northern Ohio, to residents of several towns burned by the British in 1779 and 1781.

Many awardees sold their bounties to speculators, but you still can search their paperwork. Applications, especially those by heirs, may contain a wealth of genealogical data, including military service details. Find digitized images for federal sources at GLO, Ancestry.com, Fold3 and HeritageQuest Online (use at libraries). Search an index to Mexican War pension files (which includes land warrant filing information) at FamilySearch.org. For state awards, turn to Revolutionary War Bounty Land Grants Awarded by State Governments by Lloyd deWitt Bockstruck, indexed at Ancestry.com, and to state resources such the Kentucky Land Office website.

After the initial government grant or patent, look for subsequent land transactions in deeds recorded by county or territorial governments. These are generally indexed by the buyer (grantee) and seller (grantor) names. Some indexes and deed books have been microfilmed. Search the FamilySearch catalog by place for microfilmed records you can rent at a FamilySearch Center near you. Or search WorldCat for holdings at other libraries that may be available through interlibrary loan.

4. Go After Taxes

Settlers of the West could elude many of society’s ills, but not the taxman. Though vexing to your ancestors, tax records may be the only regular source of information you find on frontier folks—at least those who were free men of a certain age, landowners, slaveholders or owners of owned certain types of personal property.

The most obvious thing you’ll learn from tax records is what your ancestor owned that the government considered worth taxing. Land was taxed at varying rates depending on its quality, location and permanent improvements made. Carriages, jewelry, livestock, musical instruments, closets and other luxury items were sometimes taxed. Slaves were taxed because they were considered property, so searching out the slaveholder’s tax records can be helpful to those researching enslaved ancestors.

Also interesting are delinquent tax lists that may indicate your ancestor struggled financially. Other details may show up, too, such as family relationships and property transfers.

Use tax records to establish a relative’s location during a particular time period, keeping in mind that he may not show up during the first few years of ownership if the land purchase was tax-exempt for a time. A person’s presence or absence from the records may hint at other possibilities, too. Poll or head taxes were assessed in some areas on every free man over (and sometimes under) a certain age. The first time a young man appears in a poll tax may indicate that he reached the age of majority: 16, 18 or 21. Sometimes sons are assessed under the father’s name for the first few years of majority. If you see an ancestor’s listing with the term “heirs” or “hrs,” you’ll know the person has recently died and the pending estate is being assessed.

Look for taxation on multiple levels: by the territory or state, county and city. Records may be in a variety of places, so you’ll need to do some detective work. State, regional and county genealogical guides may point you in the right direction. Start with the state archives, then county offices and regional archives. Also search the FamilySearch catalog by place (try the state, county and city). Duplicates may exist, for example, the Arkansas state auditor kept copies of county tax records (now at the Arkansas State Archives).

What about federal taxes? Our ancestors paid these during certain time periods, too. The most complete series is for the period between the Civil War and World War I. Many of these Civil War-era tax assessment lists are on microfilm at NARA with copies at the FHL, and indexed on Ancestry.com. Other frontier tax records are indexed on Ancestry.com, too: Find more than a million records each in indexes for frontier Ohio (1800-1850) and Texas (1846-1910) and about 30,000 records in Kentucky, Tax Lists, 1799-1801.

5. Count on Censuses

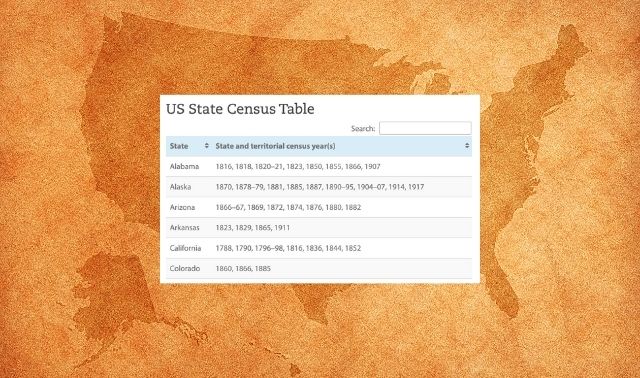

The US government was quick to enumerate settlers in new frontiers it acquired, as part of the decennial federal census or in a special census. Many early censuses contain sparse data, but can lead you to land, tax and other records.

Consult state genealogical guides to learn when the first census was taken and where you can find it. State archives often have records of the earliest censuses taken in the area, and copies may be on FamilySearch microfilm. New territories were included in the first federal census after formation, such as the 1850 census for Utah Territory. The Atlas of Historical County Boundaries can confirm which territory an area belonged to during a given time; for example, Wisconsin was originally part of Michigan Territory; Nevada was part of Utah Territory. Federal censuses are searchable online at subscription sites Ancestry.com, Findmypast.com and MyHeritage.com; as well as at HeritageQuest Online (free through many libraries), the free FamilySearch.org, and other websites.

Many Midwestern and Western states have at least limited territorial census data available outside the decennial census. Michigan Territory’s 1827 census is indexed at Ancestry.com. Oregon censuses beginning in 1842 are on FamilySearch microfilm, with some at Ancestry.com. Some frontier states participated in an optional federal census in 1885: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, North and South Dakota. (The 1885 census and others taken through 1895 for Iowa, Kansas, Nebraska, New Mexico and Wisconsin are great substitutes for the missing 1890 federal census.) Other enumerations that weren’t strictly censuses—such as lists of free white males, landowners or other groups—also may exist. Consult State Census Records by Ann S. Lainhart (Genealogical Publishing Co.), Census Finder and state genealogy guides.

6. Peek at Diaries and Histories

Most settlers didn’t blaze their own trails into the frontier. Waterways were the first highways: The Ohio River was almost entirely navigable from Pittsburgh to the Mississippi River; both rivers had downstream steamboat traffic by 1811. In the mid-to-late 1700s, the first major land routes opened into the Appalachian highlands, many along Indian paths or military routes. Canals were built primarily in the 1820s and 1830s, but were quickly supplanted, first by regional railroads and then by transcontinental lines in 1869.

Trail and canal maps, atlases and regional histories can help you guess which roads and waterways an ancestor traveled. First, see Family Tree Magazine’s map of popular US migration routes. Then look to more detailed atlases and histories to see when particular roads were built or waterways came into use. You also can search digitized migration maps at the University of Utah’s website. Find a directory of websites with trail maps, timelines and histories at Genwriters.

Little official documentation exists today of group travel to the West via wagon train or other means, with two notable exceptions: The first is Mormon pioneers. The Church History Library has documented more than 300 travel companies; consult a name and company index at LDS.org. The second is for travelers by ship from the east around South America to San Francisco. You’ll find a directory of passenger lists as early as 1846 at SFGenealogy.org.

Many frontier travelers documented their own journeys, though. Some trail dairies and retrospective accounts appear in published histories or are digitized and online. Even if your ancestor didn’t write one and isn’t mentioned in one, these accounts can teach you about your ancestor’s experience on the road. The most abundant writings are for major overland routes to the far West: the California, Mormon, Oregon and Santa Fe trails. Some accounts are published in books such as Pioneer Women: Voices from the Kansas Frontier by Joanna L. Stratton (Touchstone) and Dreams Across the Divide: Stories of the Montana Pioneers edited by Linda Wostrel (Stoneydale Press). Use WorldCat to find frontier travel accounts in regional archives and university libraries such as the Newberry Library in Chicago and the Special Collections Department of the University of Texas Arlington.

Online archives also document frontier travels. The Oregon-California Trails Association indexes names from more than 3,500 documents about the Oregon and California Trails at Paper Trail. You can search for a name here and subscribe to the site for a report on the historical documentation bearing that name. The free Trails of Hope has an index and document images for multiple trails. Also check out Pioneer Story, an interactive presentation of the Mormon trek west.

7. Study Early Settler Societies

Every frontier state from Ohio to Oregon takes pride in its pioneers. If you identify an ancestor who was an early resident of a territory, state or county, look for compiled biographies, lineage society files, card files, databases and other commemorative collections. Each collection may be a little different, but generally, here’s what you can expect:

• Compiled biographies of early settlers in many areas were published in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Look for titles such as Memorial to the Pioneer Women of the Western Reserve by Gertrude Van Rensselaer Wickham or Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah by Frank Ellwood Esshom online and at libraries. County histories also often name early settlers. Read these with caution, as the writers often cared more about glorifying early residents than accurately documenting their lives. Use details such as a residence or arrival date as clues to search for land, tax and other records.

• Card files and databases for many regions provide information on pioneers compiled from newspapers, church records, tombstones and other scattered sources. Sometimes these databases reference compiled biographies and other published histories. The Western States Marriage Record Index, for example, indexes nearly a million marriages in eleven states. The Oregon Historical Society keeps a Biography Card File with vital data on early residents; the Oregon State Archives also has a searchable Early Oregonians Database of pre-1860 residents.

Similarly, the California State Library maintains a card file with nearly 750,000 records extracted from newspapers, county histories, manuscripts and other sources (search a partial database on the website). The library’s pre-1860 pioneer card file is indexed at Ancestry.com. Mormon pioneers are indexed in many resources, including Early Latter-day Saints: A Mormon Trail Pioneer Database;. Search for resources such as these at state, regional, university, historical and genealogical repositories and on their websites.

• Lineage societies honoring early residents may have resources similar to those above and files on descendants of pioneers. Look for organizations such as The Sons and Daughters of Montana Pioneers. Many state and regional genealogical societies have “First Families” or “Early Settlers” lineage programs, too; this is true for the Ohio Genealogical Society and for most of its county chapters.

Lineage societies require members to submit an application with documentation on ties to pioneers, such as vital records, narrative histories and even photographs, as well as contact information for distant cousins. The society may have an index to applications on its website, or you may need to contact the society to request a search.

As you can see, rich sources may exist on your frontier ancestors. But you might need to adopt their adventurous mentality to find them. You may need to travel (in person or virtually) to unexpected places. You may need to dig a little. But like those early pioneers, your faith and hard work may be rewarded when you strike genealogical gold.

Tip: The Periodical Source Index can help you find articles about areas’ early settlers in genealogical publications. You can search it using HeritageQuest Online and order copies through the Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center.

Tip: Lost track of your peripatetic ancestor? Study routes he may have traveled and look for records in places along the way.

From the July/August 2013 Family Tree Magazine

Last Updated: July 2022