Split Decisions

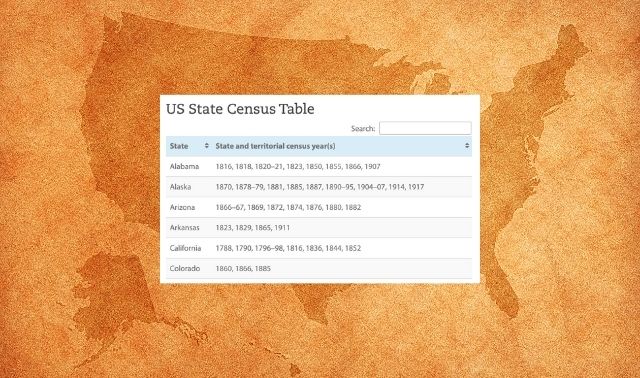

Q. My fifth-great-grandfather died in 1799 in Berkeley County, Va. This country is now in West Virginia. In which state should I research?

A. According to the Library of VirginiaWeb site<www.Iva.lib.va.us>, when WestVirginia was established in 1863, its counties retained their original local records. So for most records, contact the BerkeleyCounty clerk and the West Virginia archives(seemicrofilm holdings by county at <www.wvculture.org/historylbluenote. html>).

You’ll also find Family History Library< www.familysearch.org> records foryour ancestor’s county by running a placesearch of the online catalog. You can rentthe microfilm through your local branchFamily History Center (use Family Search to find one). The Library of Virginia has some Berkeley County microfilm, too.

Emily Anne Croom, who wrote the Virginia State Research Guide in the December 2005 Family Tree Magazine, says Berkeley County marriage records begin in 1781;land, probate and court records, in 1772.

But you’ll still want to research in Virginia, since Berkeley County was formedin 1772 from Frederick County. Croom advises looking in Frederick County for pre-1772 records, in case family was there. “I’d suggest researching all the family members who might’ve been in these counties- the family ‘cluster’ — since records ofother family members might add to factson the ‘target’ ancestor,” Croom says. Plus, ancestors who lived far from theirown county courthouse may have recordson file in neighboring counties.

–

From the May 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Second Thoughts

Q. As a naming convention, what’s the proper use of Junior vs. II? If Larry Edgar Taylor’s first-born is Larry Evan Taylor, would the son be Junior, II or neither?

A. Today, families normally use senzor (elder) and lunzor (younger) to distinguish a father and son with identical names. In earlier generations, senior and junior suggested two men of the same name and different ages-but they weren’t necessarily related. Still, in my family in the 19th century, Isaac Croom Sr. and Isaac Croom Jr. were uncle and nephew. A third Isaac Croom in the extended family identified himself by adding his middle initial. If Isaac Jr. had had a son named Isaac, he could have been Isaac Croom III.

This practice is usually reserved formales. But people informally called my grandmother Fletcher Sr. and my mother Fletcher Jr. because they had identical names, although they never wrote their own names that way. More frequently, friends called them Big Fletcher and Little Fletcher.

The Roman numerals 11, II, III and so on indicate men of identical names and varying ages, even in different family lines, such as a man (Sr. or I), his nephew (11)and later h s grandson(III). To avoid confusion, some “numbered” individuals retain the designation for life, especially in prominent families. Sometimes, however, when the senior died, the junior became senior, and the third became junior-a practice that can frustrate genealogists. In my husband’s ancestry, when we read the name John Blakeney Jr., we wonder if it refers to the original junior or John Blakeney III, who was called junior after his grandfather died. We must get clues from dates and additional records to determine which John each record indicates.

No law controls these practices, and families often do what seems logical or convenient. And whatever convention one generation uses, the next might change.

Two men with similar, but not identical, names (such as Larry Edgar Taylor and Larry Evan Taylor) wouldn’t be senior and junior. When only a middle name differs, you can differentiate the individuals by including middle names or nicknames.

– Emily Anne Croom

From the May 2007 issue of Family Tree Magazine.