You’re free to choose your friends, goes the old saying, but you can’t pick your family. But what if you could, at least genealogically speaking? Besides desiring colorful and interesting ancestors —a noble here on the family tree, a horse thief there—you’d probably want to pick a pedigree that’s relatively easy and richly rewarding to research. You’d certainly want to avoid having ancestors from places whose records have been destroyed, aren’t readily accessible or never got created in the first place. Unless you’re particularly enamored of scrolling through and squinting at microfilm, these days you’d wish for ancestors whose records are searchable online. (“Why, oh why,” you might find yourself thinking, “couldn’t Great-great-grandpa have been born in a place represented on Family Tree Magazine’s annual list of 101 Best Web Sites?”)

As we wrap up our multiyear series of State Research Guides, it seems the perfect time to look back on all 50 states with this ancestral wish list in mind: Which are the states where it’s easiest—by design or by accident of history—to research your ancestry? If you’re fortunate enough to have family ties to these “best” states for genealogy, count your blessings. The rest of us can only look on with envy and hope that someday, some as-yet-undiscovered branch of the family tree leads our research there.

Adding up all these factors—with an admittedly large dose of sheer subjectivity—we’ve assembled a list of the 10 best and 10 worst states for doing genealogy. (If your ancestors come from the other 30, you can both burn with envy and take comfort in knowing that, well, it could be worse.)

bringing up the rear

In the spirit of saving the best for last, we begin by counting down the 10 worst places for your ancestors to have lived. All is not lost, though—even in the dark depths of our list, we found bright spots to share.

10. New York

As you’d expect from a state that barely makes our “worst” list, there’s good news as well as bad if you have New York ancestors. Case in point: noteworthy state censuses (later ones specify the court where an immigrant was naturalized) and New York City’s wonderful coroner’s records. The handsome

state archives Web site offers a database of New Yorkers in the Civil War.

But that’s slim pickings online, we think, for a state as large and historic as New York. And the Empire State can be a nightmare for vital-records research: Genealogy requests for an uncertified copy of a record cost $22 and may take five months or longer to process. The state’s apparent indifference towards birth, death and marriage records dates way back: It didn’t even try to enforce record-keeping until the mid-1800s, and didn’t finally succeed until the 1880s. Vital records for New York City are kept separately at the municipal archives, and availability varies by borough.

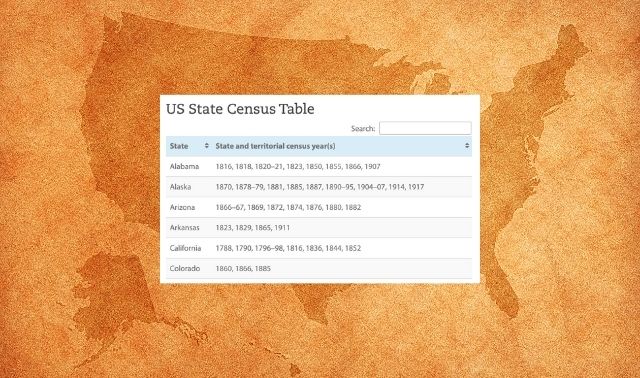

9. Idaho

Rocky Mountain and Great Plains states pepper our “worst” list, in part simply because their history is more recent and rugged. Idaho stands out—not in a good way—because of its protracted territorial era, which put it in different territorial censuses for 1850 (Oregon), 1860 (Washington) and 1870 and 1880 (Idaho). In 1860 and 1870, parts of Idaho were in the Cache County, Utah, count.

County boundaries proved equally shifty; Alturas County disappeared altogether. Idaho also caught on to vital records relatively late, starting with birth and death records at the county level in 1907 and statewide in 1911. Statewide marriage and divorce records didn’t begin until 1947. At least death certificates from 1911 to 1956 are searchable

online, and 183,000 marriages extracted from county records are in the

Western States Marriage Records Index.

8. Oklahoma

Researching your Oklahoma ancestors is not always OK. Blame its peculiar past, from Indian Territory to overnight settlements after the land rush of 1889, requiring

research in a mix of territorial, state and Indian records. That’s complicated by the loss of Oklahoma’s 1870, 1880 and 1890 federal censuses, although a special 1890 enumeration of seven counties survives and is indexed online. Even the 1900 census separates the former Indian and Oklahoma territories.

After statehood in 1907, vital records lagged in many counties until as late as 1930 and even then, are spotty until the 1940s—and there are no statewide marriage records at all. Oklahoma also lacks the wealth of online resources that many other states enjoy. But don’t despair: Land records and, for those with Indian ancestors, the Dawes Rolls can help get you past your Oklahoma roadblocks Sooner rather than later.

7. West Virginia

Like Oklahoma, the Mountaineer State suffers from a quirk of historical geography: Until the heat of the Civil War in 1863, it was part of Virginia. That means earlier records for 50 of West Virginia’s 55 counties (five were formed later) follow different rules and may be found in Virginia. West Virginia didn’t get its own census until 1870. Its oddball history also means that, despite being birthed after the US federal government, West Virginia was not a public-land state. Statewide birth and death records didn’t begin until 1917, but a fire destroyed most of them through 1921; you’ll have to look to county courthouses for earlier records, which date from 1853. It’s not all bad, though: West Virginia has put vital records on the

state archives Web site.

6. Montana

Saddled with the burdens of relatively late settlement and sprawling size—with lots of wide-open space between its cities and its genealogical repositories—Montana has a confusing early history of changing governance. From 1860 to 1880, some residents may be listed in Washington, Nebraska or Wyoming. Although Montana became a territory in 1864, births and deaths weren’t recorded until 1895 and statewide registration didn’t begin until 1907. Even then, widespread compliance didn’t happen for deaths until about 1915 and births until after that. State marriage and divorce records didn’t start until 1943, but some 10,400 early county marriage records can be found in the Western States Marriage Records Index. Land records (Montana was a public-land state, so patents are online) and the Montana Historical Society can help fill in the blanks on your Montana ancestors, but other Web resources are as sparse as this giant state’s population. Microfilmed records at the FHL are slimmer for Montana than for most states, too.

5. Louisiana

With a history residents would characterize as “colorful” and frustrated genealogists might describe as “messy,” Louisiana is one of the rare states where researchers could face a language barrier: Some early records, reflecting that history, are in French and Spanish. Louisiana is also the only state to have “parishes” instead of counties, and many parish courthouses have lost records to fires or floods over the years. Records that survive are based on French Napoleonic practices, presenting researchers with such unfamiliar terms as “conveyances” (deed transfers) and “successions” (probate). You’ll also have to become familiar with notary records, such as those collected in the New Orleans Notarial Archives; happily, you now can access these online: Click here to browse the record volumes by the notary’s name and year. Except for New Orleans, birth and death records didn’t begin until 1914. Though records for scattered pre-1805 local censuses exist, Louisiana lacks any state censuses you could use to fill in the blanks.

4. Nebraska

Although the Cornhusker State’s archives holds many records, even more are scattered among Nebraska’s whopping total of 93 counties. Many counties began keeping marriage records upon formation, but few bothered with births or deaths until statewide registration began in 1904 (1909 for marriages). Complicating vital-records research still further, only immediate kin can access birth or marriage records more recent than 50 years. As for deaths, cemeteries aren’t much help in Nebraska because the state has so many scattered and untranscribed tiny graveyards. A wealth of state and territorial censuses is the bright spot here, plus some church records that can help with vital-records gaps, federal land patents and railroad land records (although fire destroyed most Union Pacific records). Web and microfilm researchers will go away wishing their Nebraska ancestors had spent a little more time on records and a little less on cornhusking.

3. Alaska

Don’t blame the 49th state for its paucity of genealogical records: Alaska is not only new, it’s also vast and vastly different from the “lower 48.” Alaska’s genealogical troubles started soon after the United States bought it from Russia, when the 1870 census skipped the territory except for Sitka. Extant federal census coverage doesn’t begin until 1900—and don’t look by county, as Alaska doesn’t have ’em. Official vital records didn’t begin until 1913, though you can try church records before that date. Cemetery records are literally few and far between, given the state’s sprawling geography. And the Last Frontier State is still catching up with most of the lower 48 when it comes to genealogy Web sites. Land records, gold-rush papers and the National Archives in Anchorage are your best hope for tracing early Alaska kin.

2. Wyoming

Vital records are typically the Achilles’ heel of our “worst” states, and that’s certainly the case with Wyoming: Although the Equality State started recording births in 1909, these records are closed for 100 years except to immediate family—

meaning only a year’s worth are accessible to researchers. Death records, which also began in 1909, are closed for 50 years. Marriage and divorce records didn’t start until 1941; their 50-year privacy window effectively makes only 1941 to 1959 available for research. Thank goodness, then, for the Western States Marriage Records Index, which lets you search some 23,000 early Wyoming county records. When you search, however, be aware of Wyoming’s rapidly evolving county boundaries, which shifted from just five counties in 1868 to 23 by 1923. Like Montana, its neighbor to the north, Wyoming can be found in federal land records. Also like Montana, though, Wyoming’s online and microfilm resources are scanter than most states’.

1. Mississippi

Poor Mississippi. Just as it ranks worst or near-worst nationally on measures such as income equality and obesity, the state also suffers genealogically. Not that there aren’t bright spots, among them a lengthy, interesting history and the relatively new home of the

Mississippi Department of Archives and History. That intriguing past, though, has Mississippi variously under ownership of the Spanish, French and British before becoming entangled with Georgia, Alabama and Florida. The Civil War, while enriching Mississippi’s military records, contributed to document-destroying courthouse fires. Overall, more than a third of the Magnolia State’s 82 counties have suffered records losses.

Statewide birth and death records began only in 1912, with marriages and divorces lagging until 1926—and even then, there’s a gap from 1938 to 1941. Various territorial and state censuses can help when you hit Mississippi brick walls, and it is a public-land state. Further complicating Mississippi roots research, however, is the fact that it was one of only two states (the other being South Carolina) to have more slaves than free citizens in 1860. This high proportion of slaves means Mississippi is more prone to the challenges of researching African-American genealogy prior to emancipation. Combined with its courthouse losses—and not balanced out by many online resources—this inescapable difficulty drags Mississippi to the bottom of our list.

leaders of the pack

Had enough wallowing in genealogical woes and bemoaning the hard hand history has dealt some places? Let’s turn our attention to the 10 best states for researching your ancestors. Here’s hoping your family tree leads you to …

10. Texas

Big isn’t necessarily better for genealogy, as we’ve seen, but Texas overcomes its 10-gallon size—and record disasters in some 40 courthouses—with a wealth of surviving records, helpful Web sites and a world-class genealogy research center at the

Clayton Library in Houston. Records date to colonial days, including Spanish and Mexican town censuses, and to Texas’ brief era as an independent republic, in the form of

citizen claims for government compensation.

9. Minnesota

Minnesota’s genealogical prowess begins with the

state historical society, whose Web site overflows with research guides and databases of births (1900 to 1934), deaths (1904 to 2001), old photos, maps, even building and house histories. A People Finder lets you search the whole works with a single click. Offline, the society offers a Biography File of 100,000 cards indexing information about Minnesotans from publications in the society’s collections.

If your Minnesotans lived in the northern mining country, the Iron Range Research Center has plenty of ways to help you dig for them. The Land of 10,000 Lakes is also notable for remarkably few leaks in its records, including comprehensive territorial, state and federal censuses; BLM public-lands files; and vital records (county births and deaths starting in 1870, statewide births beginning in 1900, deaths in 1908, marriages not until 1958). Probate records date to territorial days. Military records include bonus payments to veterans and their survivors from the Spanish-American War through Vietnam.

8. Utah

Censuswise, the US government counted Utah Territory starting in 1850; territorial censuses exist for 1856 and 1872. Utah was also a public-land state. Other than lagging a bit with statewide vital records (1905 for births and deaths, with full compliance later still) Utah lives up to founder Brigham Young’s visions of the promised land, at least for genealogists.

7. Illinois

Home to the

National Archives and Records Administration’s Great Lakes Region and the renowned

Newberry Library, Illinois is a great place for your family to be from. One of the first states to post genealogical records online, the Land of Lincoln serves up a 1763-to-1900 marriage index, two death indexes (pre-1916 and 1916 to 1950), military and veterans records from the War of 1812 on, land records, and servitude and emancipation records, all

here. If you’re looking for more—or want copies of records—the Illinois Regional Archives Depository (IRAD) catalog tells you where to go

next. Although statewide birth and death registration lagged until 1916, counties were required to keep these and marriage records beginning in 1877. You also can find Illinois kin in federal censuses starting with 1820, 10 territorial and state enumerations and a shelfload of city directories.

6. Wisconsin

As with many of our “bests,” excellent online resources first popped Wisconsin onto our radar. These are mostly efforts of the

Wisconsin Historical Society, where you can search more than 150,000 obituaries and biographical sketches, a million births, a million marriages, 400,000 deaths, 16,000 historical and biographical articles, Civil War records and veterans’ censuses. If you’re a member, the society’s Wisconsin Genealogical Research Service even does the work for you. Add the Dairy State’s wealth of state and territorial censuses, federal land records, county and local histories, probate records, naturalization papers and vital records (which in some counties begin with marriages in the 1820s) and you have plenty of resources worth, well, milking. The state didn’t begin keeping vital records until 1907, but Wisconsin has plenty of other ways (such as an abundance of church records) to get the genealogical goods on your ancestors.

5. Arizona

Here again, we confess to being seduced by the ease and power of a state’s online records. Arizona, however, stands alone in this instance: It’s the only state to post

searchable databases of birth certificates (1855 to 1932) and death certificates (1844 to 1957), which you can then—here’s the clincher—click on to view PDFs of the actual records. Note, too, the chronological reach of both certificate collections (encompassing some delayed certificates), which puts to shame even many states that entered the union long before Arizona got its star in 1912.

The Grand Canyon State’s history is further captured in seven territorial censuses (not all complete, but all available and four indexed), Great Registers of voters from 1882 to 1911 (later for some counties), the 100,000-name Arizona Biographical Database, and the state library’s newspaper collection dating from 1864. Besides that excellent state library and archive, Arizona also boasts the country’s largest FHL branch Family History Center, in Mesa; and the

University of Northern Arizona’s Colorado Plateau Digital Archive, which hosts a searchable collection of photos, letters, diaries and the like. The only hitch comes with marriage and divorce records, which—although starting back in 1864—are archived by each county’s superior court. But don’t fret: Arizona has only 15 counties, an added genealogical boon.

4. Missouri

Another online pioneer, the Show Me state shows you a wealth of resources at its superb

Missouri State Archives site. A birth and death records database encompassing 185,000 pre-1910 entries from 87 counties will help you overcome Missouri’s relatively late statewide vital- records start. You’ll also find databases of death certificates (1910 to 1957), naturalization records (1816 to 1955), court records, land patents and even coroners’ inquests, plus searchable military records on more than 576,000 Missourians from the War of 1812 to World War I.

3. Virginia

The Old Dominion State has one unassailable advantage over the other 49, epitomized by that word “old”: America started here in 1607, bequeathing Virginia centuries of records. Not all have survived, it’s true—39 county courthouses lost records to fires or other calamities over the years—and Virginia’s vital records are not as neat as you might like (though birth and death registration began in 1853, there’s a gap from 1896 to 1912). But the sheer volume of other records makes up for these glitches. The

Library of Virginia excels at making these resources available, with online offerings including land patents and grants, 6,000 scanned family Bible records, birth and death register indexes (1853 to 1896), wills and administrations (to 1800) and Confederate pension applications. Where gaps do exist in Virginia records, you can try plenty of other sources, such as tax lists, city directories and church records. Virginia also excels in paying genealogical attention to its records, oodles of which have been transcribed in publications such as

Cavaliers and Pioneers and the

Virginia Genealogical Society Quarterly.

2. Washington

A perennial “101 Best” honoree, the

Washington State Digital Archives just keeps getting better. At last count, this ambitious effort to digitize the Evergreen State’s past topped 75 million records, with 63 million of them searchable—many linked to record images. Holdings vary by county, but include birth, death and marriage records; territorial and state censuses dating to 1847; the 1860, 1870 and 1910 federal censuses; military records; land records; naturalization papers; and even a database of the state’s physicians. Equally impressive is a project to digitize historical Washington newspapers from the state library’s collection of more than 40,000 microfilm reels. To date, 19

newspapers variously covering 1852 to 1892 have been scanned and made searchable, including a search by personal names.

Offline Washington research riches include the

National Archives Pacific Alaska Region in Seattle. A public-land state, Washington didn’t begin statewide birth and death registration until 1907 (but many counties had jumped the gun by 1891) or marriage records until 1968 (here, too, many counties already were recording marriages). With few historical flaws and two outstanding digitization projects, Washington ranks No. 2 on our best list—but with a footnote: Next time, we wouldn’t be surprised to see it rise to No. 1.

1. Massachusetts

Some consider tracing their ancestry back to the Mayflower the Holy Grail of genealogy. But whether your Massachusetts ancestors arrived in 1620 or long after the Pilgrims, you’ll find a bounty of records for researching them. Any other state would be notable just for a repository like the Massachusetts state archives, whose

Web site includes an index to vital records (1841 to 1910) and an in-progress database to more than a million arrivals through the port of Boston (1848 to 1891). But Boston is also home to the

New England Historic Genealogical Society and its library of more than 200,000 books, periodicals, and microform materials, plus 1 million manuscripts. Members ($75 per year) enjoy online databases with more than 110 million names and volumes from the series The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England and The New England Historical and Genealogical Register.

Massachusetts boasts not one but two National Archives facilities, both covering the Northeast, in

Pittsfield and

Boston. As for censuses, federal coverage starts at the very beginning, in 1790, with only a few hiccups in 1800 (but a 1798 tax list can help). State head counts in 1855 and 1865 happily coincide with a peak immigration period. Statewide vital records began in 1841, but town records for the most part date to each locale’s founding. City directories as old as 1789 can fill gaps. Military records are another treasure trove for Massachusetts research. And if you do happen to have Mayflower ancestors, these folks have been genealogically documented more than any other Americans. No wonder their Massachusetts landing pad is the top US launching point for roots research.

state guidance

Family Tree Magazine State Research Guides can help you discover your roots in the top 10, bottom 10 and any state in between. You can get the whole collection (plus Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico) on a convenient, fully searchable

CD or a library-quality hardbound

book; or download individual guides from

Family Tree Shop.