I come from “good stock.” That’s what my grandpa has always told me, pointing to the long lives of his “people” who spent the last two centuries scraping by in the rural Kentucky counties of Lincoln and Clay. To prove his point, he often runs through a laundry list of relatives whose life spans have spiked into the 80s, 90s, even 100s, in a time and place where most people were lucky to make it to their 60s or 70s. “All my people are good people,” he says with pride. “They’re good-hearted people. You’ve got some good, long-lived stock in you.”

If your roots lie in the broad, beautiful region of Appalachia, you, too, have probably wondered what your people were like — who they were and how they made their way in the forests and hollows of the mountains and valleys. The tips, resources and historical information here will help you discover your own Appalachian roots and all the fascinating stories surrounding them.

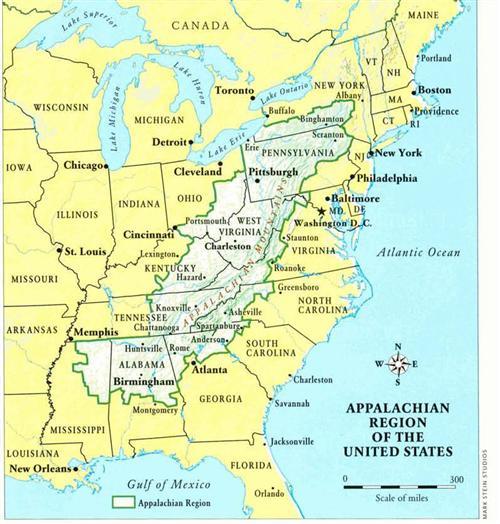

Before you can even begin searching for your Appalachian roots, you need to know how the region is defined — and where your kin fit into that definition. Though it’s one of the oldest names on American maps, Appalachia has never had a fixed set of boundaries. Over the centuries, various authorities with their own agendas — political, geographical, cultural and historical — tried to shape the region in different ways.

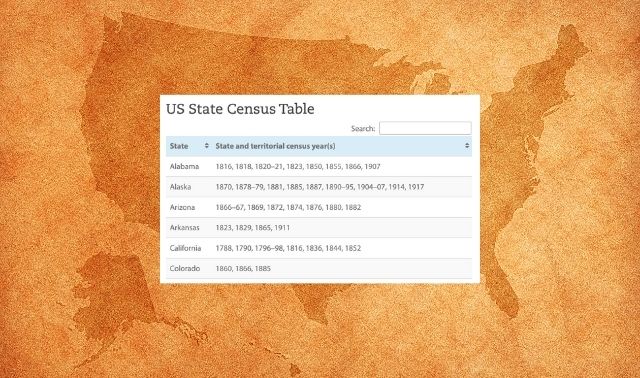

Finally, in 1965, a government agency called the Appalachian Regional Commission decided that Appalachia officially encompasses the following areas and states: northeastern Mississippi, northern Alabama, northwestern Georgia, eastern Tennessee, western North Carolina, the northwest tip of South Carolina, eastern Kentucky, western Virginia, all of West Virginia, eastern and southern Ohio, western Pennsylvania, southern New York and the western tip of Maryland. (For a complete list of counties in the region, visit the Appalachian Regional Commission’s Web site <www.arc.gov/index.do?nodeld=27>.)

THE EARLY HILLS AND VALLEYS

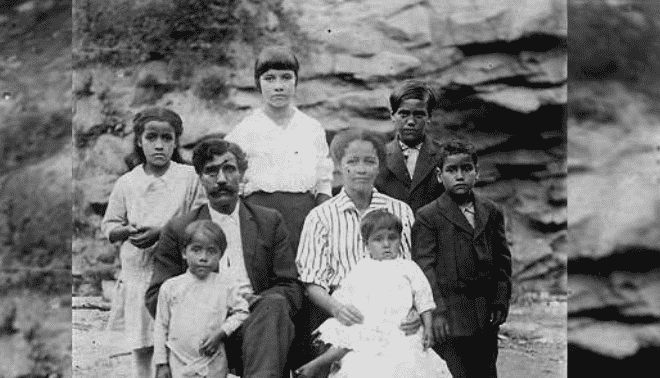

Before Spanish explorers came to Appalachia looking for gold in 1539, the region was home to Native Americans. About 60,000 Cherokees lived in or near the mountains in what is now South Carolina, North Carolina and Tennessee. The Shawnees lived in southern Ohio, and the Creeks in Georgia. In the 16th century, the Iroquois formed a confederacy of Indian nations to build up strength against the white settlers beginning to infiltrate their lands. During the next century, this confederacy worked its way south, attacking tribes and building an empire throughout Appalachia, while British, French and Spanish forces fought for land on the coast. As white explorers ventured into Appalachia, Africans who had been forcibly brought to America often accompanied them.

In his book Appalachia: A History (University of North Carolina Press), John Alexander Williams says such conglomerations “remind us that the European and native peoples that collided in Appalachia during the latter half of the 18th century were on each side multiethnic, multilingual societies shaped by earlier generations’ experience of warfare, migration and disease.”

And collide they did. The mountain ranges of Appalachia were a barrier to early westward expansion because there were few passes, but eventually several major east-west routes were opened up through river valleys and mountain notches. For a century, white settlers pushed west and south into the mountains and valleys, displacing Native American populations and claiming the land for themselves. From 1730 to 1763, European-Americans moved into Appalachian Pennsylvania and Maryland, as well as parts of western Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Then, through 1789, European-Americans settled in eastern Tennessee, northwestern North Carolina, northwestern South Carolina and central Kentucky. For the next 30 years, white settlers pushed their way into southern West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, southeastern Ohio, the Great Valley in eastern Tennessee and the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in western North Carolina.

Finally, the Cherokee nation was displaced from southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama. This displacement of Cherokees ended tragically with their forced removal in 1838, when they had to move to their new home in Oklahoma after being held in hot, disease-ridden stockades for the summer. Some 1,500 Indians died in the stockades; another 4,000 died along the Trail of Tears.

A MOUNTAIN MELTING POT

Who were the peoples moving into Appalachia during this rime, and how did they get there? “They were Anglo-Saxons, of English descent; Scots-Irish from Ulster, Northern Ireland; and Germans, Irish, French Huguenots and soldiers from the Revolutionary War who had been given land grants as payment for their service to the government,” says Carolyn Wilson Dyer, a professional genealogist based in Georgetown, Ky. “They traveled down the Great Philadelphia Wagon Road to Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee — this route was heavily populated with travelers.

INDUSTRIALIZATION TAKES HOLD

My grandfather, Oscar Britton, spent part of his childhood in those company towns. He lived in Harlan County, Ky., for the first 13 years of his life, moving from school to school as his father, Alfred Britton, moved from mine to mine in places such as Shoestring and Clover Splint. Alfred was never a coal miner, though. Instead, he worked for the businesses surrounding the coal mines, such as sawmills, which produced the lumber that propped up the mines, and delivery services, which took coal by horse and buggy to townspeople.

People like my great-grandfather, who worked for mining businesses, didn’t get paid in dollars. The mine companies issued their own currency called scrip, coins that looked like silver dollars and had the company’s name imprinted on them. Grandpa recalls seeing his father head out for the commissary — the company store — with his hat full of those silver scrip dollars. Drifting back to those days, Grandpa starts to sing in his baritone voice:

Some people say a man done made out o’mud, A poor man made out o’muscle and blood, Muscle and blood and skin and bones, A mind that’s weak and a back that’s strong, Load 16 tons and whaddya get, Another day older and deeper in debt, Saint Peter dontcha call me cause I can’t come, I owe my soul to the company store.

When the Great Depression hit Appalachia, many people left the mountains for nearby cities. Others stayed behind and struggled through decades of poverty.

REGIONAL RESEARCH HOT SPOTS

With such a rich ethnic, social and cultural history, tracing your Appalachian ancestry will prove a rewarding pursuit. And while there aren’t many books or Web sites dedicated to Appalachian genealogy, you’ll find some excellent resources for the region as a whole:

• The West Virginia University Library Appalachian Collection <www.libraries.wvu.edu/appalachian> has an outstanding collection on the 13-state Appalachian region, and much of it is indexed and annotated in the Appalachian Bibliography, published by the university. The collection has more than 5,000 volumes on topics ranging from coal miners to Cherokee Indians, as well as publications such as Appalachian journal, Appalachian Heritage and the journal of Appalachian Studies.

• The Center for Appalachian Studies and Services at East Tennessee State University <cass.etsu.edu> offers multimedia materials documenting the political, economic, social and cultural history of southern Appalachia. The center’s holdings include manuscripts, business and organization records, photographs, audio and video recordings of musical performances, and oral history interviews.

• The Center for Virtual Appalachia <cva.morehead-st.edu> is a terrific resource for learning more about Appalachia “as a distinct and unique region of the United States.” The Web site contains many helpful links in categories such as culture, arts and crafts, music, literature, religion and genealogy.

• The W. L Eury Appalachian Collection at Appalachian State University’s Center for Appalachian Studies <www.library.appstate.edu/appcoll> includes county records for western North Carolina and northeastern Tennessee, family histories of Appalachian families, and all available censuses for all Appalachian counties. The collection also contains manuscripts, maps and early newspapers.

• The Southern Appalachian Archives and Historical Collections at Berea (Ky.) College <www.berea.edu/library/special.html> feature manuscripts, photographs, records, tapes and films relating to the history of the Appalachian region, the college and the Berea community.

• The Eastern Kentucky University Special Collections & Archives <www.Iibrary.eku.edu/sca> has selected manuscripts, institutional records, diaries, genealogical records, photographs, films, electronic records, maps and memorabilia “of continuing and enduring value that document Kentucky history and literature.” Materials cover many Appalachian counties.

GOING LOCAL

When you start figuring out which states and counties your Appalachian kin called home, your best bet is to localize your search. All of the states in the region are well-represented on the Web and in guidebooks, library collections and other resources. Start with the state’s Research Outline from Family Search <www.familysearch.org> (click the Search tab, then Research Helps), which provides an overview of history, records, libraries and tips for getting started researching in a state. You also should visit the state’s USGenWeb site (go to <www.usgenweb.com> for a link) to learn about that state’s resources and to link to your ancestral county’s GenWeb site. Another good starting place is Cyndi’s List www.cyndislist.com, a directory of more than 190,000 categorized links to genealogy Web sites (browse the links listed under your state). And of course, plan to research in the local record repositories, either in person or from afar.

VISIT THE HOMESTEAD

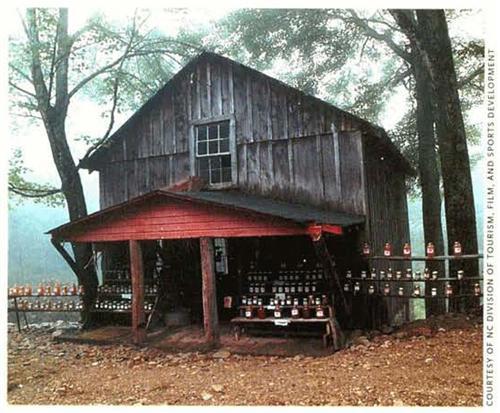

Today, tourism is one of Appalachians biggest industries, and with good reason. It’s a gorgeous region, filled with a great variety of flora and fauna (think magnolias and bears!) and plenty of cultural sites. Visit your ancestors’ old stomping grounds if you know where they are or just know the general vicinity. I accompanied my grandpa on a visit to the places in eastern Kentucky where lie grew up, and it was one of the most enjoyable days of my life. For him, seeing those places jogged his memory and helped him tell more stories. For me, I was able to learn firsthand how he grew up, and finally put together all those pieces of family history I had been gathering for years.

From the December 2003 Family Tree Magazine