When you think of online immigration and passenger-list research, the first sites that come to mind are probably those for Ellis Island or its predecessor, Castle Garden, or a volunteer site like the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild. But you also should think of the subscription site Ancestry.com . In addition to its rich collections of censuses, vital records, newspapers and other resources, Ancestry.com has built up an impressive toolkit for solving the often-intractable problem of “crossing the pond.”

Ancestry.com divides its Immigration and Travel collection into six categories of databases: Passenger Lists, Citizenship and Naturalization Records, Border Crossings and Passports, Crew Lists, Immigration and Emigration Books, and Ship Pictures and Descriptions. Some databases are indexes; many link to images of original records.

You can search all these databases at once, by category or one at a time. And because you can pop back and forth with other Ancestry.com records, you can easily cross-reference data about an ancestor: Find your ancestor’s year of naturalization or how many years the 1900 census says he’d been in America, for example, and use that information to locate naturalization and passenger-list records. Best of all, you can use most of the collection free at libraries offering Ancestry Library Edition.

Getting started

To get started searching Ancestry.com’s immigration records, from the home page, hover over Search on the navigation bar. Select Immigration and Travel from the menu that drops down. If the Advanced search form isn’t already displayed, click Show Advanced in the green bar above the search blanks to give yourself the most options. To search only a single category of records, use the links under Narrow by Category on the right.

If you want to search just a single database — say you know your ancestor sailed from Germany and you want to find him in Hamburg Passenger Lists, 1850-1934 — scroll down a little and click the View All in Card Catalog button. It’s a big list, 314 databases at last count, ranging from “19th-Century Emigration of ‘Old Lutherans’ from Eastern Germany to Australia, Canada, and the United States” (56 records) to “Sons of Utah Pioneers — Card Index, 1847-50” (1,800 records).

Among the most popular — and, not coincidentally, the largest — immigration and travel databases you’ll find on Ancestry.com are:

- New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 (82.9 million records)

- Passenger and Immigration Lists Index, 1500s-1900s (4.7 million)

- UK Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878-1960 (16.3 million)

- Selected US Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1966 (2.7 million), 1790-1974 (1.2 million) and 1794-1995 (2.5 million)

Other popular databases cover Canadian passenger lists (1865-1935) and border crossings from Canada to the United States (1895-1956). Most major US ports are represented among passenger lists, such as Boston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Orleans and California ports. You can even trace your ancestor’s travels back to his hometown in the old country, if he’s in the database of US passport applications (1795-1925).

In our step-by-step example below, I happened to be searching for an emigrant from Sweden. Ancestry.com now has a Swedish Emigration Records, 1783-1951, database. Those with German, British, Canadian, Swiss, Irish and Scottish ancestors will likewise find many records to search, while some specific databases cover certain Latvian, Lithuanian and Italian immigrants.

Understanding searches

Ancestry.com’s search interface, introduced in 2008 and frequently updated, lets you enter a variety of facts about your ancestor — the more the better — then produces a list of results in order of relevance, ranked by stars. Because of all the inaccuracies inherent in old records, the search uses a sort of “fuzzy” logic, assuming that the criteria you enter aren’t exact. Search filters give you more control: Click Exact to make Ancestry.com search for, say, “Harold Higgins” and not “Harold Higgens” or “Hal Higgs.” You also can choose Exact plus any combination of Soundex matches (last names only), phonetic matches, names with similar meanings or spellings, and records where only initials are recorded (first and middle names only). Place searches — including birth place, residence, place of arrival and departure, and place of origin — can be refined to encompass adjacent counties or states.

When you refine your results by birth dates, the search engine assumes an automatic “fudge factor” of five years before and after the date you type in. Or you can still check Exact for either birth or migration date and select your own fudge factor of one, two, five or 10 years.

The Advanced search form also has a checkbox where you can universally “Match all terms exactly.” But don’t go wild with that Exact option until you’ve at least seen what results you get from casting a broad net. When you specify “Exact,” remember, records that don’t contain that piece of information simply get skipped: A passenger list that doesn’t enumerate ages (or that doesn’t give your ancestor’s age) won’t be included if you enter an “Exact” birth year, even if you choose a plus/minus range.

Even with the new “exact plus” options, you may want to use wildcard characters to account for oddball spellings not ordinarily caught by Soundex. This can be especially important with immigration records, which involve unfamiliar foreign names and places, as well as accent marks. Wildcards substitute for letters in the name you’re searching for. A question mark (?) serves as a single-character wildcard, while an asterisk (*) replaces zero or more characters.

Keep a few rules in mind when searching with wildcards: You can use a wildcard at the beginning or end of a name, but not both. You must use at least three actual characters in an asterisk search; searching for Jo* produces only an error message. But it’s fine to use more than one wildcard in a search: Typing Leibo?i?z retrieves Leibowitz, Leibovitz and Leibowicz. Searching for Leibo* not only gets those names but also Leibold, Leibovsky and probably more other variants than you want to deal with.

You can even search without a name at all, as long as you have enough other data to narrow your quest. For example, you could search for all Lithuanian passengers born in 1881 who arrived at New York in 1897. You might use this technique to circumvent the genealogical brick wall of surnames changed in America. My ancestor whom I knew as Oscar Lundeen, for example, was born Oscar Ingelsson — who would have guessed?

Learning a little about pronunciation in your immigrant ancestor’s native language can also help you find elusive names, as can trying ethnic equivalents of familiar American names: Johann for John, Giuseppe for Joseph, Mikhail for Mike.

Refining your search

When you click Search, you get a ranked list of possible matches. You also might see a note prodding you to enter more data to improve your search. Once you’ve run that initial search, you can speed up your record-viewing and search-refining by using these “hot keys” on your keyboard:

- n = start a new search

- r = refine your search

- p = preview the current record

- > = highlight the next record

- < = highlight previous record

You can refine your search by adding more information: an ancestor’s country of origin, for example, or a date range. The Keyword field accepts single words, multiple words or phrases enclosed in quotation marks. If you know the name of the ship your ancestor sailed on, try entering it in the Keyword box. If you think you know your ancestor’s town or province in the old country, type it into the Origin box and see if Ancestry.com “suggests” a complete place name (such as Thanet, England, United Kingdom). If not, try the place as a Keyword (don’t make it Exact, since spelling variants are common).

As you accumulate clues, you may want to focus on a single category or database. To view results by category, such as Crew Lists, click the box to the left of your search results, which also shows how many hits you have in each category. When viewing by category, the box lists hits by specific database. If you click on the name of a database (Minnesota Naturalization Records Index, 1854-1957, for example), you’ll see only results from that resource; selecting Learn More About This Database jumps to a page where you can start a fresh search in just that database.

Tracing ancestors’ journeys to America can be a genealogist’s greatest challenge. If you have access to Ancestry.com, however, you may discover you own a powerful spyglass for peering back across the Atlantic.

Tip: Don’t be put off by confusing passenger list entries under “to what country belonging” — it may merely indicate a country where your ancestor boarded a ship to begin the second (or third) leg of his journey.

Ancestry.com Immigrant Search: Two Examples

Searching for Early Arrivals

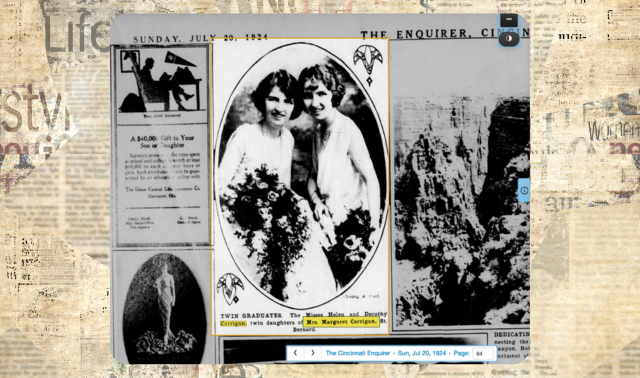

While there are plenty of options for finding ancestors who arrived in the great waves of the 19th and early 20th centuries, what about those who came to America before it was the United States? Ancestry.com can help find the elusive origins of these Colonial ancestors, too.

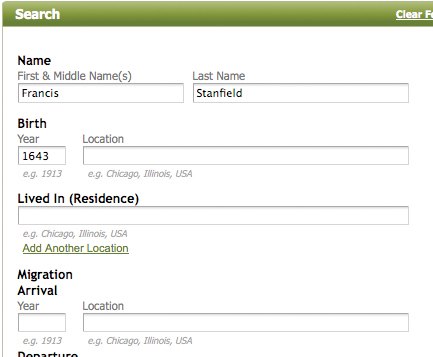

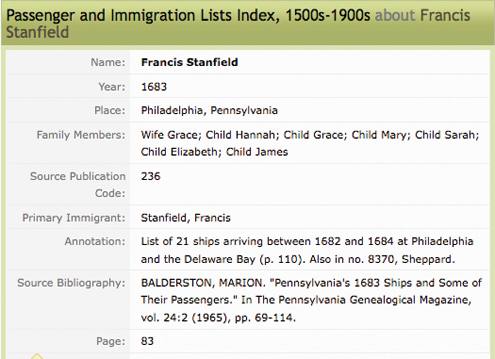

1. Francis Stanfield is way back in my family tree — my seventh-great grandfather — so I didn’t have much information to fill in the blanks in an online search form. For these bare bones, Ancestry.com’s basic search form would do. Note that it doesn’t give you the Exact or “Exact plus” choices for dates, names and locations.

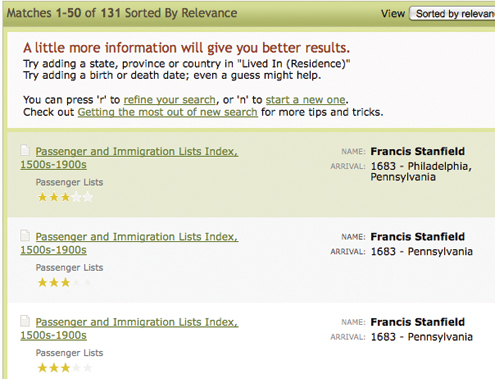

2. The upside of this simple search was that not very many people born about 1643 were coming to America from anyplace. Luckily, not knowing much about Francis Stanfield proved no problem: I got hits right away — and I could ignore the site’s nag about “A little more information will give you better results.”

3. The first three hits proved to contain similar information, but look what a gold mine! Not only did I find the year and arrival port in Philadelphia, but the names of his wife and the children who accompanied them.

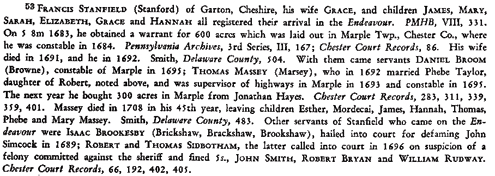

4. Going back and clicking on a match (further down the list) to the digitized book Passengers and Ships Prior to 1684, I got a lengthy writeup — a footnote to a brief listing for Francis Stanford (Stanfield) narrowing his arrival to July 1683. Besides details about the traveling party (even their death dates) and the name of the ship (Endeavour), this footnote includes the critical data that they came from Garton, Cheshire — I’d “jumped the pond” in tracing them back to England.

Finding Post-1820 Immigrants

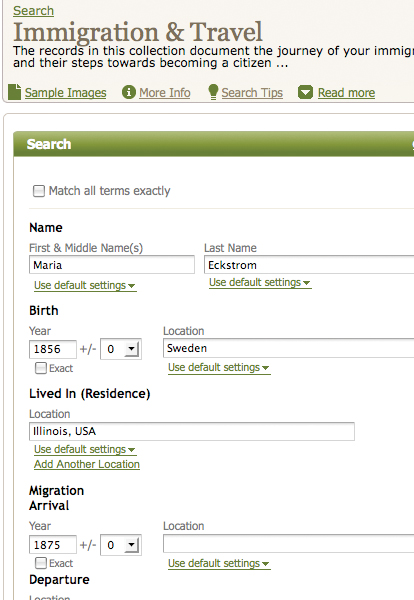

I knew my great-grandmother Mary Eckstrom (Maria Ekström back in Sweden) had immigrated to America about 1875, based on her listing in the 1900 census. But I’d struck out completely searching for her at CastleGarden.org, the free site with an index to arrivals at the port of New York prior to Ellis Island. Could Ancestry.com help solve this puzzle?

1. In Ancestry.com’s main Immigration and Travel Advanced search form, I entered the basic information I was most sure of, typing the name Mary used in Sweden and presumably on her first US records. I entered my best guess of her birth year, plus 1875 for the migration date — but I didn’t check Exact for either, to see what Ancestry.com would come up with. (Selecting male or female from the Gender drop-down box at the bottom of the search form can dramatically focus your finds, though some passengers may have been mistakenly miscategorized.)

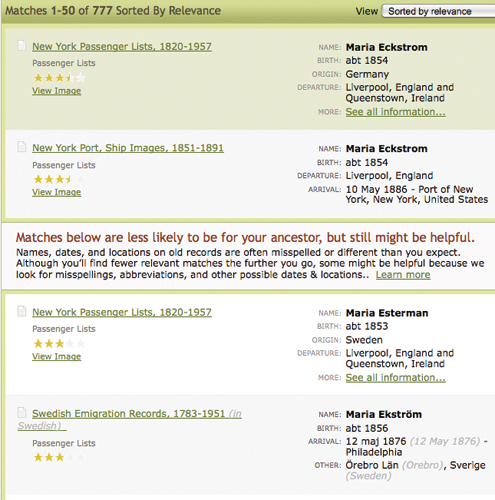

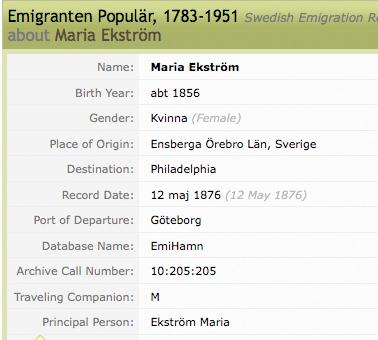

2. After hitting Search, at first I was disappointed. But Ancestry.com’s results — and how it ranks them — are only as good as the data you enter. I’d forgotten to type Sweden in the Origin field, thinking I’d covered that by saying she was born in Sweden. So my top results were both German women who immigrated in 1886. Not my Maria — not even close. “Maria Esterman,” the first 3-star entry, was clearly a miss, too. But hold on: Further down the list, what about Maria Ekström, born about 1856, arrived May 12, 1876 (not 1875, but our ancestors weren’t always precise about dates when responding to the census enumerator)? Plus she’s even from the right county, Örebro.

Don’t despair if the first few results from a very general search fail to match your ancestor. Keep scrolling down and add your intelligence to that of the software search engine. I wouldn’t have thought to be so specific as Örebro, for instance, but once I spotted it among the results I knew I had my great-grandmother.

3. Not all Ancestry.com immigration databases are linked to images of original records, but this transcription gave me the crucial information I needed: Mary has arrived in Philadelphia, not New York, and left Sweden in 1876, not 1875.

4. Refining my search to add the exact migration year and place of arrival, I now got the Swedish emigration record plus Maria’s Philadelphia passenger list as my top two hits.

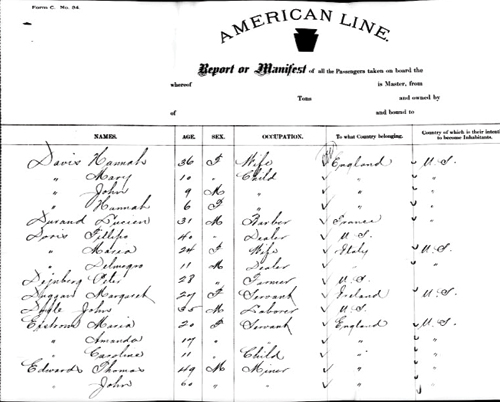

5. Picking the Philadelphia link, I could click to an image of her original arrival record. And look who’s listed right after her: sisters Amanda and Caroline. The sisters traveled from Sweden to England to book passage to America, a common pattern.

A version of this article appeared in the January 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine.