Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

For example, during the 1840s, women wore daycaps (bonnets made of starched white cotton) for everyday and special occasions. By the 1850s, this headgear had fallen out of fashion, though elderly women continued to wear them for several more decades. If you have a picture of a relative wearing one of these hats in her youth, the image likely dates back to the 1840s. (Of course, you’ll have to examine other clothing clues to be certain.) Once you’ve narrowed the photo’s time frame, you should consult your genealogical records to determine whether your female ancestors’ ages at that time correspond to the age of the picture’s subject. With luck, you’ll find a match.

You don’t have to be a fashion maven to spot clothing clues in photographs. Just follow these identification tips and our 19th-century fashion-trend timelines, and you’ll be putting names to those mystery faces in no time.

Style basics

ADVERTISEMENT

Begin by enlarging segments of an unidentified picture with a magnifying glass or by scanning it. Examine every detail of the subject’s outfit. Look at the shape of a woman’s bodice, neckline, sleeves and skirt — and don’t forget accessories and hairstyle. Pay attention to a man’s coat shape, trouser width, necktie style, hairstyle and accessories. Any of these details could clue you in to when the photo was taken. Of course, shoe styles have changed, too, but they’re usually difficult to distinguish in old photos.

Most family portraits show relatives dressed in their “best.” In the 19th century, popular magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book advised women on what to wear. But if your ancestor lacked the latest accessory, some studios kept shawls, pins and hats on hand for patrons to borrow. After all, a happy customer meant repeat business and referrals.

Our ancestors’ economic circumstances did influence their clothing choices, but style variations between classes usually aren’t significant. Women who lacked financial resources or lived in rural areas still followed fashion trends — they would remake dresses or add a few accessories to fit the current styles.

ADVERTISEMENT

You’ll find more-significant style variations in portraits of recent immigrants or ancestors living in foreign countries. These differences actually could simplify the identification process, though. For instance, a headdress worn for a wedding photo could tell you whether the image comes from your Russian mother’s side or your Scottish father’s side of the family.

Dating a photograph through costume requires some knowledge of fashion history — and that’s easy to get. Here, we identify key components of 19th-century fashion since the advent of photography, decade by decade, so you can start solving even your toughest picture puzzles now.

What women wore

Women’s fashion has changed dramatically through the years, so even the length of a skirt or the shape of a sleeve can help you date an image. Accessories such as gloves, jewelry, hats and fans have fallen in and out of fashion, which means they can aid identification, too.

The basic elements of our female ancestors’ clothing remained the same regardless of their economic status. Pants weren’t popular until the mid-1900s, so women typically wore dresses. Frugal women often pieced together two or more dresses to create an outfit reflecting current styles. Be on the lookout for dresses with bodices and skirts made of different materials.

Before drawing conclusions about your photographs, be sure to add up all the clues, rather than focusing on a single style detail. When in doubt, make a list of an outfit’s significant characteristics. Look not only at the shape of a sleeve, but also the width of the cuff. Since most women made their own clothes until the 20th century, you will see some style variation. But watch out for these common elements:

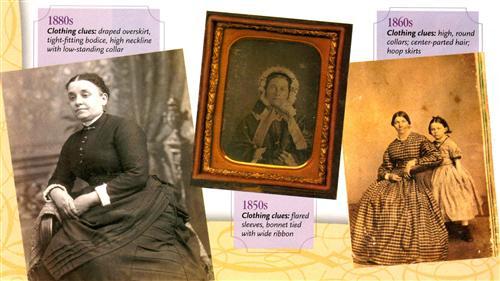

1840 to 1849: The first photographs, known as daguerreotypes, appeared in the United States in 1840. Throughout the next decade, a resurgence in religious and moral conservatism led women to dress in modest, restrictive clothes, which often inhibited natural movement, according to Dressed for the Photographer by Joan Severa. Worn over corsets, back-fastening dresses had long, tight bodices with fan-shaped gatherings. The wide, shallow, horizontal necklines gradually narrowed later in the decade, when high-standing collars came into vogue. Sleeves were long and tight, especially on the upper arms. Popular accessories included fingerless gloves, gold watches on long chains, ribbon bracelets and bonnets that extended past the chin. Women wore their hair close to the head, with a center part, long ringlets and large combs.

1850 to 1859: Women’s fashion loosened up a bit in the 1850s, and ladies’ magazines such as Godey’s increasingly reported on the trends. Dress sleeves were still narrow at the shoulder, but flared at the wrist, revealing white undersleeves. Our ancestors fashioned full, gathered or pleated skirts over hoops, and favored dresses with more trim and color. Women parted their hair in the center and let it droop over their ears. They also experimented with ornamental hair jewelry, and wore bonnets off the face and tied with wide ribbon. By mid-decade, front-fastening bodices with broad collars gained popularity. At the end of the 1850s, collars narrowed, and sleeves gathered at the wrist once again.

1860 to 1868: During the Civil War, women selected bodices that buttoned down the front and had pointed or round waists decorated with military braid. Most dresses featured high, narrow, round collars, but some had V-necks with lapels. Sleeve styles varied: Some came in at the wrist, and others flared. Skirts worn over hoops were pleated, and some looped up (with assistance of cords on the inside of the skirt) to expose underskirts. Women accessorized with shawls, hairnets, wide belts, elaborate earrings and brooches. They wore their hair with a center part and covering their ears. Some opted for braids or short ringlets. Bonnets changed shape from round to oval early in the decade. As hairstyles became more elaborate after the war, women sported smaller hats.

1869 to 1874: Ruffles were all the rage during this era: Bodices featured ruffles and large, prominent buttons; necklines were high with low-standing collars, or V-necks with ruffles; and some moderately bell-shaped coat sleeves had ruffles. Skirts were trimmed with apron-like overskirts, and bustles — some quite large — expanded underskirts. Accessories included black velvet neck ribbons with brooches or charms attached to the front, large lockets on gold chains, crosses, and long jet-bead necklaces with matching earrings. Women continued to part their hair in the center, and began to wear false locks with large combs. They often braided their hair at the crown and left the rest streaming down their backs. Small hats and bonnets trimmed with feathers, lace and flowers accented these high, full hairstyles.

1857 to 1877: During the mid-1870s, waistlines lengthened, and two-piece dresses gained popularity. Front-opening necklines featured low collars or V-necks with ruffles. Sleeves were narrower and decorated with trim. Skirts began to lose their fullness, and had long overskirts and trains.

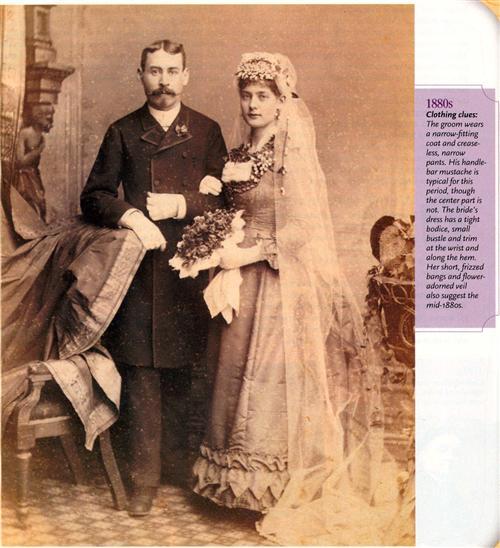

1878 to 1882: By the late 1870s, the full hoop skirt had gone out of style, and the bustle disappeared. Skirts now fell straight from hip to floor. Front buttons adorned tight-fitting bodices, which came down over the hips. Necklines were high with low-standing collars, and sleeves remained narrow. Women continued to part their hair in the center, and wore short, frizzed bangs.

1883 to 1889: By the mid-1880s, women had entered the work force as secretaries, telephone operators and department-store clerks, and demanded less-restrictive clothing. Draped overskirts, often apronlike in shape, appeared. The bustle returned in 1883 and reached its maximum size in 1886, before deflating the next year. Tight bodices extended below the waist, and had high necklines with low-standing collars. Tight, three-quarter-length sleeves with trim at the wrist also were popular. Look for lace parasols, muffs and novelty jewelry. Hair remained frizzed around the face with a bun in back. Women chose hats in a variety of styles, the most popular being high-crowned hats with wide brims and elaborate trim.

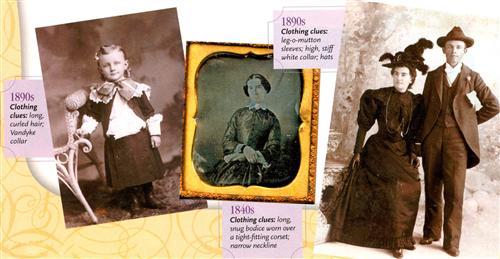

1890 to 1900: The demand for less-restrictive clothing increased as women began to exercise outdoors. As a result, corsets loosened, and shirtwaists came into vogue. Necklines had high collars worn to the chin. In the early 1890s, women wore large, balloon-like “leg-o-mutton” sleeves that were tight at the wrist. After 1896, sleeves got smaller, with fullness at the shoulder and a slight flare over the hand. Skirts were smooth at the hips, but flared dramatically. Between 1893 and 1896, women favored feather boas, large fans and parasols. At the end of the decade, they accessorized with small earrings, watches pinned to their bosoms, and small decorative combs worn high on the back of the head, but visible from the front. Short bangs, worn with a small topknot, remained popular during the first part of the decade, but went out of style by 1896. Then, women parted and flattened their hair into waves along the temples. Although older women still sported bonnets, most young women had switched to hats, especially small hats with vertical trim. By the end of the decade, wide-brimmed hats also were popular.

Clothes make the man

Men’s clothing is harder to date because style varied little in the 19th century. Their dress clothes comprised a coat, shirt, trousers, necktie and possibly a vest. Work attire consisted of a collarless shirt, no tie, pants, suspenders and sometimes a vest. The best clothing clues are hats, vests and shirts, as these garments changed the most over time. You’ll have to look closely for subtle clues.

1840 to 1849: During this decade, men wore coats with extra-long, narrow sleeves; tailored white shirts with narrow sleeves and small turned-up collars; and dark-colored neckties in horizontal bowknots. Smocklike work shirts came in a variety of colors and patterns. Men kept their hair at ear length and parted high on one side. Most were clean-shaven, but some sported fringe beards that framed their jaws. Hat styles included wool stocking caps, black felt bowlers and shiny silk top hats.

1850 to 1859: Narrow sleeves remained stylish into the first part of the 1850s. Around 1854, generously cut suit coats (worn with vests) and wide-legged pants came into vogue. Shirt collars turned over 2-inch-wide neckties, worn in wide half-bows. Men wore dress shirts in a variety of colors and patterns. They also bought fancy starched shirtfronts to dress up their attire. Most men were clean-shaven until the end of the decade, when full beards appeared. They wore their oiled hair long on top and combed into a wave at the center of the forehead. Later in the decade, their hair grew long enough to cover the ears. Young men wore cloth caps, which resembled railroad caps. Tall black hats with flat brims also gained popularity.

1860 to 1869: Men’s suit coats came in a range of new shapes in the 1860s — the most popular being the long, oversized sack coat, worn with wide-legged pants that were longer at the heel and held up by suspenders. A white, striped or plaid shirt and narrow necktie completed the look. Men parted their ear-length hair on the side and grew whiskers, rather than full beards. After the Civil War, they continued to wear military caps to work.

1870 to 1879: The popular sack coat got shorter and narrower during this decade, and buttoned only at the top in order to display the vest and watch chain worn underneath. White, striped and plaid shirts were made without collars — our ancestors bought those separately. They wore wide black or striped neckties in loose knots with overlapping ends. Fur hats and coats also gained popularity at this time.

1880 to 1889: In the 1880s, men’s coats got even shorter and narrower, and they closed high at the throat, nearly concealing the necktie. Our ancestors wore these coats with narrow, creaseless pants and wide shirts. Neckties varied in width. Throughout the decade, young men sported a wide variety of hats, from straw sailor hats to black homburgs (felt hats featuring dented crowns and shallow, rolled brims), which businessmen favored.

1890 to 1900: Narrow was the key characteristic of 1890s men’s fashion: narrow coats worn buttoned to the top, narrow black or patterned bow ties and narrow trousers. White shirts had small, stiff, pointed collars at the beginning of the decade and high, stiff collars at the end of the decade. Men wore their hair short and grew large mustaches. Bowlers and derby-style hats’ popularity exploded during this decade.

Kid-friendly fashion

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, babies of both sexes wore long dresses; current adult fashion trends dictated the gowns’ lengths and details. Toddlers sported shorter dresses to accommodate movement. The best way to tell girls and boys apart is to look at their hairstyles. Girls usually wore their hair parted in the middle, and boys’ hair was parted on the side.

Parents dressed their older sons in short pants and their daughters in dresses. Children’s fashion generally followed the same trends as adults’. As children grew older, their clothing styles changed — which enables you to estimate a child’s age based on his or her clothing. For instance, the length of a girl’s skirt gradually got longer as she approached adulthood. Boys wore short pants until approximately age 12, then donned long pants.

Frances Hodgson Burnett started a fashion trend for boys when her book Little Lord Fauntleroy was published in 1886. Until the early 20th century, mothers dressed their sons in outfits that mimicked those in the book’s drawings by Reginald Birch. A typical outfit consisted of a white shirt with a full Vandyke collar (a large linen or lace collar with a scalloped edge), a satin sash, a plumed hat and long, curled hair.

All in the details

Not only can clothing help you date an image, but it also can clue you in to your ancestors’ experiences. Keep an eye out for these telling details:

• Traditional ethnic dress: Upon arriving in America, immigrants often abandoned their full ethnic dress so they could better assimilate. But occasionally, accessories such as caps, head scarves and mantillas will identify their ethnicity. Robert Harrold’s Folk Costumes of the World (Sterling Publishing Co.) offers an overview of clothing styles around the globe.

• Fraternal-order regalia: You might find photographic evidence of an ancestor’s membership in a fraternal order, such as the Freemasons, Modern Woodmen of America or Elks. Medals, buttons, ribbons, badges, sashes and jewelry (including watches, fobs, pins and rings) could contain symbols and slogans of one of these organizations. For tips on researching fraternal orders, see the June 2004 Family Tree Magazine.

• Military uniforms: Studying headgear, buttons, shirts, pants, weapons and decoration can date a photograph and provide evidence of military service. For instance, during the Civil War, many Union volunteers wore belt buckles with their states’ abbreviations; Confederate soldiers wore buckles with the letters CSA, which stood for Confederate States of America. If you’re trying to trace Civil War ancestors, those belt buckles could give you enough clues to locate military records.

• Occupational clothing: Look for hats, aprons or props suggesting your ancestor’s employment. Consult Dressed for the Job by Christobel Williams-Mitchell (Blandford Books) for pictures of people on the job.

• Religious attire: Photos of altar boys, priests, nuns and other people in religious garb can be difficult to date because the clothing styles don’t change. But these portraits can provide clues about your ancestors’ religious affiliation. Look for Bibles, candles, flowers and other religious symbols.

Collective evidence

As you add up all the costume clues in your photographs, remember: Looks can be deceiving. Just because your ancestor’s outfit seems to date to the 1880s, that doesn’t mean it actually does. For example, in some tourist spots, you can have your picture taken in period clothing. One of my friends has a tintype of himself in a Civil War uniform. Not only did the photographer copy the 19th-century photographic process, but the clothing looks authentic. To an unsuspecting descendant, this photo might appear older than it actually is.

It’s easy to misidentify both the person and the time period if you look only at costume clues. Wedding pictures, for instance, can offer conflicting evidence if the bride wears an heirloom gown. So be sure to look for other hints, such as props, before drawing a conclusion.

Once you’ve used costume clues to estimate a picture’s time frame, consult magazines and store catalogs from that period, or flip through books with historical photos to confirm your analysis. If you’re still having trouble placing the photograph within a fashion context, you might want to consult a costume professional. Some historical societies and museums have staff who specialize in costume history.

Over the years, I’ve developed a fascination with historical fashion. The clothing provides glimpses into our ancestors’ everyday lives and insights into their personalities. The next time you pose for a picture, think about what you’re wearing — and what those clothes will say to your descendants.

From the September 2004 Trace Your Family History.

ADVERTISEMENT