Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Say you discovered an old letter hinting that your grandmother was divorced before she married Grandpa. Or you found your great-grandfather’s naturalization records, but not his wife’s. Or you have no idea whether vital records exist for your Colonial Maryland kin. What now?

Hitting the books — the legal books, that is — could lead to the answers you seek. From birth certificates to bounty land warrants, there’s a law behind just about every official record genealogists use. Laws governed how our ancestors went about petitioning for divorces, applying for naturalization, registering births and deaths, purchasing land, joining the military, and so forth. And the laws your ancestors lived by can give you insight into the historical and social framework of their lives, explain why counties and states have different records and record-keeping practices, and offer clues to where records are located. But you don’t have to go to law school to reap these rewards — just take this quick course in three types of old laws that affected your forebears.

Public affairs

Laws affecting the general population in a jurisdiction are called public statutes or acts. They can be state or federal, criminal or civil. Legislatures use them to create and regulate government offices and agencies — and in the process, generate records that are useful to genealogists. For example, in November 1781, the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia passed “an Act for Ascertaining Certain Taxes and Duties, and for Establishing a Permanent Revenue.” Part of this act stated:

ADVERTISEMENT

… the two commissioners … shall proceed to take an account in writing of the quantity of land belonging to all persons within their said county … also of the name of the proprietor or proprietors thereof, and shall ascertain the value of the said lands by the acre…

The act created a system of taxation to begin in February 1782. It dictated how to assess property in each county, report the assessment, collect the taxes, and punish those who didn’t pay up. Later sections describe taxes on polls (legal voters), servants, slaves, personal property and imported goods.

This created a new record group. If you have Virginia roots, these post-1782 property tax lists make a good substitute resource for the lost 1790 and 1800 US censuses for Virginia. The product of a state law, the poll tax records are kept on the state level at the Library of Virginia; a transcript is available at FamilySearch.org. (Keep reading to learn which levels of government tend to have which genealogical records.)

Public statutes also governed how births, marriages, deaths and burials were recorded. Say you have Roman Catholic ancestors who lived in Colonial Maryland, but no Catholic Church records exist for them. Brick wall, right?

ADVERTISEMENT

Wrong. Researching a little deeper into the colony’s public statutes identifies the March 1701 “Act for the Establishment of Religious Worship, according to the Church of England, and for the Maintenance of Ministers,” which confirmed the Protestant Episcopal Church (Church of England) as the official religion of the colony. Among its provisions:

Each Vestry shall, and is obliged to provide a fit Person for a Register, who shall … make true Entry of all Vestry Proceedings, and of all Births, Marriages, and Burials (Negro’s and Mulatto’s excepted). …

All residents, regardless of religious faith, had to register births, marriages and burials with the Protestant Episcopal Church. As a result, plenty of post-1701 births, marriages and deaths of Maryland Catholics are recorded in Episcopal registers. Many Colonies had similar requirements, opening an entirely new path for researching Colonial Catholic families. After the American Revolution, record-keeping responsibility often transferred to towns and counties. By the early 1900s, almost all states had passed laws requiring counties to track births, marriages and deaths, and to send copies of records to state health departments.

Federal cases

Congress has enacted hundreds of laws to generate census, immigration, land and other federal records. These are some major ones; learn more about finding federal records in the article below:

Census laws

As each constitutionally required decennial federal census neared, Congress enacted laws to establish details such as what questions would be asked. The 1790 census was the result of “an act providing for the enumeration of the inhabitants of the United States,” passed March 1, 1790. The act specified the information collected: the names of heads of households and the numbers of free white males over 16 years old and under 16 years old, free white females, other free persons and slaves. The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) keeps census records, but this genealogical go-to source is readily available online at subscription site Ancestry.com and free site FamilySearch, and on microfilm at NARA facilities, the Family History Library and many large public libraries.

Immigration record laws

Congress regulated incoming passenger ships and the immigration of foreigners. March 2, 1819, Congress passed an act requiring:

the captain or master of any ship or vessel arriving in the United States … shall also deliver and report, to the collector of the district in which such ship or vessel shall arrive, a list or manifest of all the passengers taken on board of the said ship or vessel at any foreign port …

These manifests are the passenger lists we use to identify when our ancestors immigrated. No federal passenger lists exist prior to 1820, when the law went into effect; any earlier lists would’ve been collected by a state or local entity where the ship arrived. NARA is the custodian of 1820-and-later passenger lists, but they’re also available online and on microfilm in many of the same places you’ll find censuses.

Congress also established procedures for immigrants to become citizens. Until 1906, they could file for naturalization in any courthouse, making their records hard to locate. The Basic Naturalization Act of 1906 centralized the process under the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization; you can order post-1906 records from the US Citizenship and Immigration Service. Before the Married Woman’s Act of 1922, a woman automatically became a citizen when her husband did — perhaps explaining why you couldn’t find Great-grandma’s naturalization papers.

Land laws

Through legislation, Congress outlined how federal lands could be distributed. Different laws regulated the distribution depending on the land’s location, the recipient and the time period: Some land was granted as a reward for military service, some was given to settlers for fulfilling specific terms of residency or improvements (such as farming or planting trees), and some was sold for cash.

Take the 1837 patent establishing John M. Clemens as owner of land in Monroe County, Mo., “… according to the provisions of the Act of Congress of the 24th of April, 1820.” The document also describes the land John purchased.

In adhering to the 1820 act that the patent cites, “An Act making further provision for the sale of Public Lands,” the government created more records about John M. Clemens’ claim. They include his application to purchase the land and any personal documents he supplied with it. These records, in addition to the patent, make up his land entry case file. Federal land patents are online. John M. Clemens’ son Samuel, born in 1835, later wrote about life in Missouri under the pen name Mark Twain.

The May 20, 1862, Homestead Act “to secure Homesteads to actual Settlers on the Public Domain” stated the person applying for land had to be the head of a family and at least 21 years old, or a veteran or member of the US Army or Navy. The applicant had to affirm he or she was a US citizen or had begun the naturalization process, and that he or she had:

… never borne arms against the Government of the United States or given aid and comfort to its enemies, and that such application is made for his or her exclusive use and benefit, and that said entry is made for the purpose of actual settlement and cultivation …

Approved applicants paid a $10 fee to settle on the claimed land. After five years, a settler had to prove he’d resided on and cultivated the land for the entire period. Only then would the land patent be issued.

This law lets you infer additional facts about homesteading ancestors. You know where your ancestor lived for at least five years prior to receiving the patent. You know an immigrant who obtained land under this act had either become a citizen or filed a declaration of intent to naturalize; clues in the land entry case file will help you find naturalization records (especially handy for those records prior to 1906).

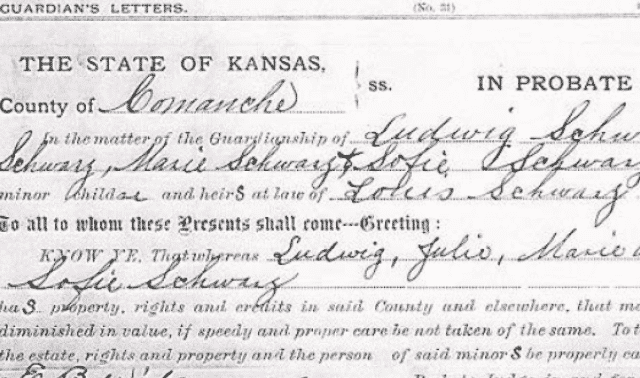

Private assistance

Both state and federal legislatures occasionally took up the causes of individuals. “Private acts” could involve the granting of pensions to veterans whose claims were denied through normal avenues, extensions of land claims, and other forms of relief. These private acts often contain interesting details about our ancestors’ lives.

For example, April 12, 1870, the US Congress passed an “Act to Compensate Mrs. Fannie Kelly for Important Services,” ordering the treasury to pay Kelly $5,000 for:

… services rendered the government in [1864], by giving information to Captain James L. Fisk, in charge of a train crossing the plains, and to Major House, in command of Fort Sully, of the evil designs of hostile Sioux Indians …

State legislatures also may have passed private acts involving state and county taxes and the probate of estates. In some states, legislatures would hear divorce cases and pass private acts granting or denying a divorce petition — this was the case in Pennsylvania until 1874 and Delaware until 1897.

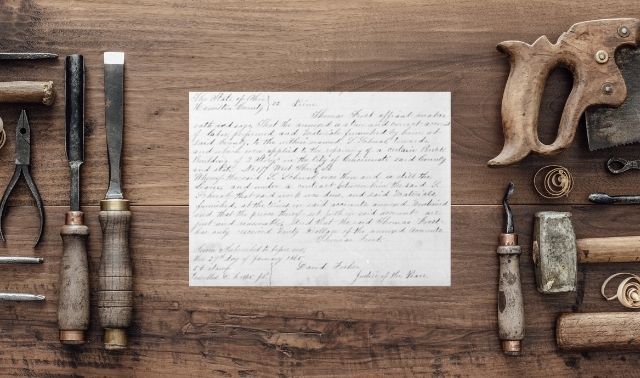

Legal research

Ready to look into the laws behind your ancestors’ records? Start online with a search on the topic of interest, such as 19th century naturalization laws. You might find a resource with the information you need about the laws you’re interested in, without having to squint through pages of statutes.

If you need to check the language of laws your ancestors abided by, you might still have luck online. The Maryland State Archives, for example, has digital images of published session laws (laws that were passed in a given legislative session), legislative proceedings and other documents in the Archives of Maryland Online and Early State Records. New York has digitized books published statutes for various years in the 19th century. Look for digitized books of your ancestral state statutes on the state archives, state library and local university libraries’ websites. Also try searching Google Books and Internet Archive for books of statutes. For example, a search for statutes South Carolina returns a digitized copy of The Statutes at Large of South Carolina, published in 1836. If you know a state passed a private law affecting your ancestor, include the term “private law” in your search. To narrow your results, add your ancestor’s state, for example: “private laws” Kansas.

Find out more about federal laws from 1789 to 1875 in the federal Statutes at Large, digitized in the Library of Congress’ American Memory project.

Not all historical laws are published online. University, state and local law libraries have series of books compiling state and federal legislation. These books are generally chronological and aren’t always indexed by topic, so you’ll need an idea of when the law in question was passed. You may need to enlist the help of a librarian and seek advice from experts at the local historical society or state archives. Channeling your inner lawyer and looking to local, state and national statutes can net key clues about your ancestors’ lives and where their records are.

Tip: If a private act may have affected your ancestor, look for indexes or abstracts, such as Genealogical Abstracts of the Laws of Pennsylvania and the Statutes at Large by Candy Crocker Livengood (Family Line Publications).

A version of this article appeared in the September 2011 issue of Family Tree Magazine

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT