Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you!

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

As was typical for many children, I gleefully spent summers visiting my grandparents, along with my older brother. My granddad took us out on the water in his motorboat, and my grandmother set up the little blue plastic pool in the yard where we splashed away the hot day.

She would also send us on errands to the local Kroger grocery store. One day my grandmother said to me, “Be sure to get a quart of milk, some bread, and some canned tuna,” as she pressed a few dollars into my sweaty palms and hurried us on our way to the store. But I was preoccupied, sidetracked by the cute mailboy making his way towards the house. It’s no surprise that I forgot even the few items on the list that day.

Thankfully, I had a witness—someone else who could corroborate what was said and done. My brother, unmoved by the curly-headed boy, quickly recounted the items we were responsible to bring home. I didn’t know I was getting an early lesson in the value of witnesses, one that I would later apply to researching the ancestors of those same grandparents.

As genealogists, we emphasize scouring each source, mining for details that may initially seem unimportant. The presence of witnesses or bondsmen in records is one such detail that we can’t afford to miss. Though they may have a surname we don’t recognize, these “side actors” become tiny threads that, when pulled, can reveal a world of information we never expected to find.

Here’s why and how you should pay attention to witnesses and others mentioned in records. And the case studies below will show how these individuals can help your research.

Who are the Witnesses and Bondsmen in Records?

For genealogical purposes, a witness is someone who saw an event happen. Like my brother ahead of that grocery store visit, a witness stands beside us and can attest to what took place. This means they have firsthand knowledge of an event. In a world of skeptics to every conceivable action, witnesses are critical, and provide verification for others who are not present at the time.

A bondsman (or surety) is also a witness. But they have a more-active role in the event, making a financial guarantee that they’ll support the other person (bondholder) in fulfilling their obligations and/or complete the terms of an agreement themselves if the bondholder fails to do so. Like loan co-signers today, bondsmen were often close family members—you wouldn’t make a financial guarantee for someone you don’t know well!

Here are some common people who might serve as a person’s witness or bondsman:

- Sons

- Sons-in-law

- Brothers

- Brothers-in-law

- Fathers

- Fathers-in-law

- Uncles

- Male cousins

- Close neighbors

- Fellow church members

- Business associates

Certain documents tended to require witnesses or bondsmen:

- Deeds

- Wills

- Marriage bonds or licenses

- Guardianship bonds

- Administrator or executor bonds

- Court appearance bonds and civil case records

- Baptisms and christening certificates and registers

In addition, some of the above (as well as military pensions and Southern Claims Commission documents) required witness testimony, even if the witness’ physical presence was not required.

Genealogy Clues from Witnesses and Bondsmen

Witnesses and bondsmen are important in court actions, both today and in the past, providing credibility to legal evidence and added assurance to financial transactions. We can exploit their prominence in records to create portals to the world of our ancestors.

How? As previously stated, witnesses and bondsmen are frequently well-known to those for whom a record is being created. They often form part of a person’s “FAN Club,” an acronym popularized by genealogist Elizabeth Shown Mills that refers to a person’s Friends, Associates and Neighbors. Researching a person’s FAN network, also referred to as “cluster research,” encourages us to explore people beyond our direct-line ancestors.

People did not live, move, associate, work, worship or marry in isolation. (Neither do we today!) Instead, they lived their lives in networks. As such, FAN Club members may appear in records that are relevant to our ancestors as well. Not all records require witnesses or bondsmen. But those that do can provide a rich avenue for research.

An appearance in “someone else’s” record establishes that a person was physically present at a specific time and place, a key goal for genealogists. That, in turn, can help us determine when someone migrated from one country or state to another, or help distinguish one same-named person from another.

Serving as a witness or bondsman can also suggest other information about a person, namely:

- Age or birth year: Witnesses and bondsmen usually had to be of legal age, often 18 or 21 years old.

- Residence: They often lived near where the event took place.

- Literacy: Did the person sign their name, or simply mark it with an X? The latter suggests the person couldn’t write.

Not all records require witnesses or bondsmen. But those that do can provide a rich avenue for research.

Robyn N. Smith

3 Steps for Researching Witnesses

1. Transcribe the document

Transcribing information in a record—that is, re-writing its text in another medium—forces us to take time to focus on sources, bringing to light minute details that we might not have noticed if we’re struggling to even just read the text. Is the copy legible, and can we clearly make out every word? Does the document include terms that we don’t understand?

Genealogy has simple, well-defined rules for transcription; Sunny Morton shares some transcription tips. Today, tools abound to make the task even simpler. (I especially like the free GenScriber.)

2. Identify names, then research them

Once you have a transcription of the document’s text, look for the names of all people mentioned in the document—not just the record subject or people named as witnesses. For the moment, add them to your cluster, and research them as if they were all your relatives. Note that people (especially bondsmen) are sometimes listed by first or middle initials and last name; you’ll need to do some more research to confirm their identities.

Look for all those people in other records, and try to find information that fleshes out their lives. Consider researching county biographies (often available at a local library or genealogical/historical society), which sometimes name individuals.

Make sure you also look at the few entries before and after your document of interest, which might list other local officials. Some will end up being family members. Others might simply be a county clerk, a lawyer or justice of the peace. Post-nominal letters suggest the person’s role in the community and identity as public officials.

3. Research the laws

As genealogists, we need to have a deep understanding of the sources we use, including how and why they were created. Laws governed everything about relevant kinds of records: where, when or if an event was documented; who was required to be present; what information was recorded and how it was formatted; what fees were required; and which officials (such as notaries public) were allowed to perform certain functions. Later laws affected how that information was stored, which government office held custody, and who has access to the records today.

The legal jurisdiction you need to study will vary by record type. State laws, for example, are sometimes recorded in published legal histories of the state.

Laws may differ by state and locality, affecting (for example) what witnesses were required to create a document. Let’s compare deed laws in Tennessee and Maryland as an example.

Published in 1871, A Compilation of the Statute Laws of the State of Tennessee by W.J. Gilbert described the requirements for deeds that include real estate. It stated: “No deed of conveyance for land … shall be good and available in law … unless the same be acknowledged by the vendor, or proved by two witnesses upon oath.” The term “vendor” here referred to the grantor. If the grantor did not acknowledge (i.e., legally testify to) the deed, two witnesses were required.

In comparison, let’s look at Maryland in 1879, as published in Revised Code of the Public General Laws of the State of Maryland, with the Constitution of the State, compiled by Lewis Mayer, Louis C. Fischer and E.J.D. Cross. By that year, deeds related to real estate only required one witness: “Every deed conveying real estate shall be signed and sealed by the grantor or bargainor, and attested by at least one witness.”

New sources and research strategies like the FAN Club can help us answer lingering questions about ancestors, regardless of location, time period or surname. Witnesses and bondsmen are key members of that FAN Club, uncovering new family members, suggesting spouses for our ancestors, and provide clues to family origin or out-migration. Study them, and you might find the last piece of your family history puzzle.

Case Studies

All photos courtesy Robyn N. Smith.

1. In-Law Clues in Land Records

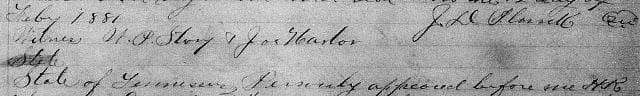

In 1881, J.D. Plunk sold 16 acres of land in Hardin County, Tenn., to SC (Samuel) Holt. The witnesses were W.P. Story and Joe Harbor. I knew from previous research that W.P. (William) Story was a justice of the peace, though that isn’t indicated in this document.

But who was Joe Harbor? A little digging revealed that Samuel Holt and Joe Harbor married the Barnes sisters; Samuel’s wife was Lucy Barnes, and Joe’s wife was her sister Hannah Barnes. The two men were brothers-in-law.

But there is something else worth noting about these two witnesses. The acknowledgment states that Samuel did not come to court to acknowledge the deed, as was commonplace. The two witnesses, W.P. Story and Joe Harbor, did instead. I’d need to research more to determine why that was the case, but it’s possible Samuel had died.

2. Finding New Siblings in Bonds

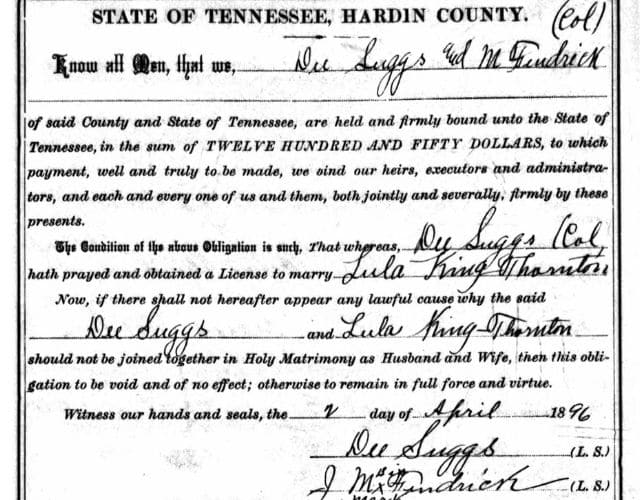

Witnesses and bondsmen have played a key role in some of my biggest discoveries. On 2 April 1896, in Hardin County, Tenn., my great-great-grandfather Mike Fendricks (“M Fendrick”) joined in a bond of $1,250 to secure the obligation of Dee Suggs’ marriage.

That certainly wasn’t the only record I found linking the two men. I noticed that Mike was listed as a boarder in Dee’s household in the 1920 census. Additionally, the men jointly signed a trust deed as sharecroppers in 1884.

Why did these men with different surnames appear with such close association? That screams FAN Club.

Years of additional research revealed that the two men were, in fact, half-brothers. Mike and 10-year-old “Dee” (enumerated as Dewitt) lived in the household of their mother, Sofrona Suggs, in Alabama at the time of the 1870 census. And a Freedmen’s Bureau labor contract between Thomas Suggs and Sofrona Suggs (called “Frony” in the record) confirmed that Frank, Mike, Caroline and Dee were her children:

“Articles of Agreement made and entered in between Thos Suggs of the first part and a lot of freed people, (to wit), Jack 13 years of age Frony thirty two & her four children, (to wit) Frank 15 years of age Mike 10 years Carry 6 yrs Dee three years of age…”

Further record research and DNA evidence supported the conclusion that Mike chose to use the surname of his biological father (Mike Fendricks), while Dee kept his mother’s surname.

3. Maiden Names in Baptism Registers

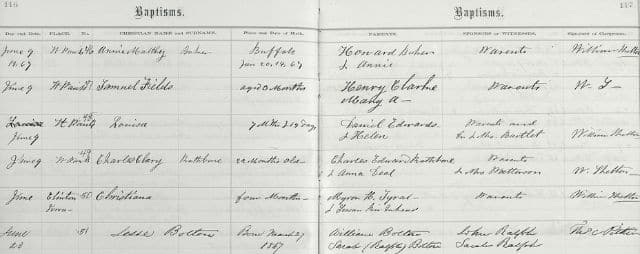

Baptisms or christenings are especially good sources for witnesses, as we can see from this late 19th-century baptism record from St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Erie County, N.Y. Jesse Bolton was baptized on 23 June 1867. (The year is technically just implied.)

His parents, William and Sarah Bolton, had witnesses (also called sponsors) named John and Sarah Ralph. Sarah’s name includes (Ralph) in parentheses, implying that was her maiden name. Further research might reveal John and Sarah Ralph to be her parents, or brother and sister-in-law.

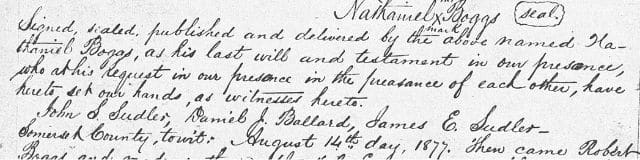

4. Neighbors in Wills

Nathaniel Boggs was a free Black man, living within a fairly large community of other freed people who mainly worked on the water as oystermen, sailors and fishermen. In fact, the area where they lived was called Freetown.

Most free Blacks needed to keep good relationships with local whites, and Nathaniel was no exception. Three men (who, from previous research, I knew were white) witnessed his 1877 will: John S. Sudler, Daniel J. Ballard, and James E. Sudler. A contemporary map shows the three men were Nathaniel’s neighbors.

A version of this article in the January/February 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine.

Related Reads

ADVERTISEMENT