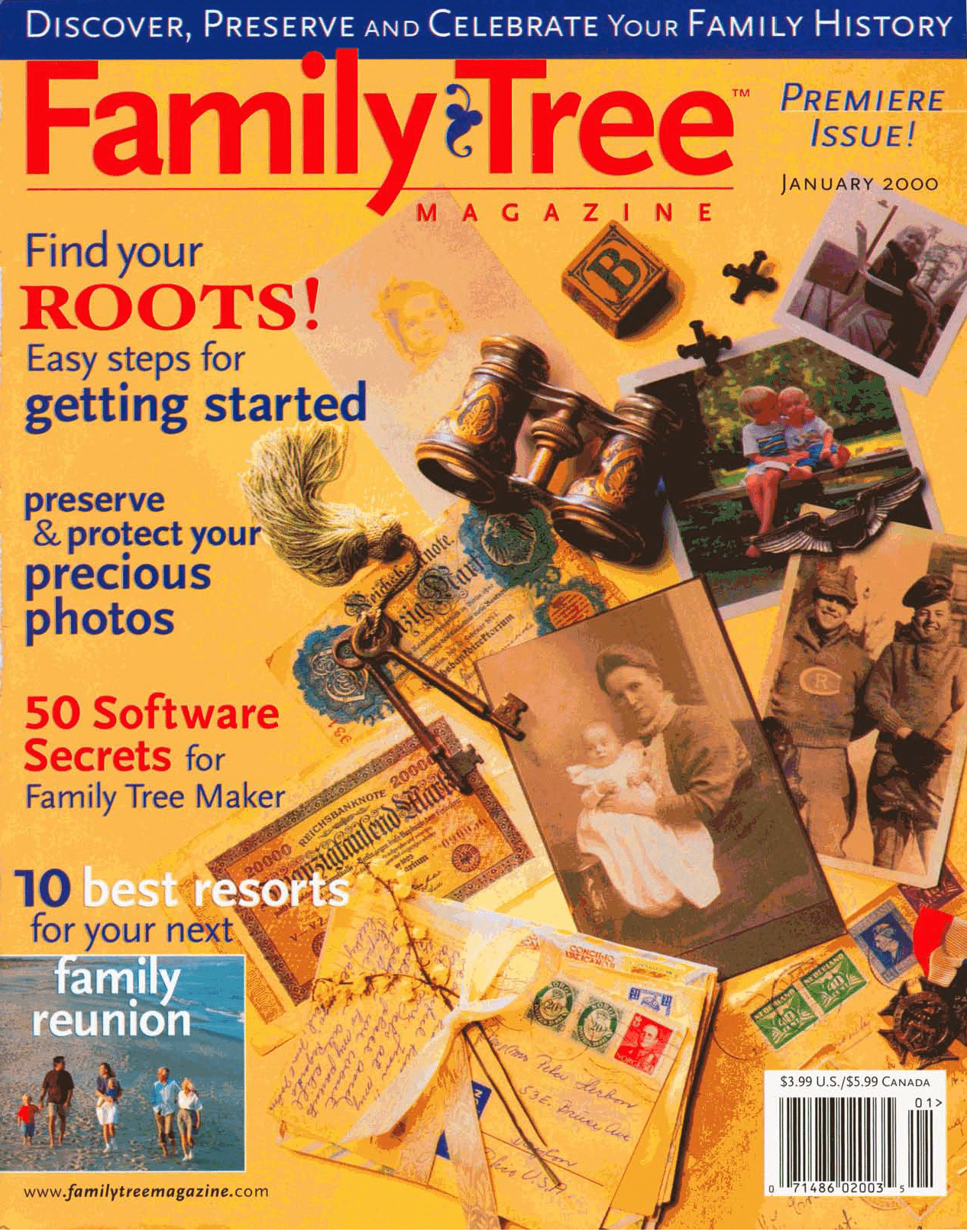

The 25th anniversary of Family Tree Magazine has our staff thinking about all the ways genealogy has changed since our first issue in 2000. Today, we find ourselves in a new era of family history—the way we do research has changed dramatically in the past few decades (and even in the past few years).

For many, the era of “modern genealogy” began in 1977. That year, the TV miniseries “Roots” premiered, inspiring a new generation of family historians.

By portraying an oft-neglected part of history (the lives of an enslaved African and his descendants in the United States), this pivotal series—and the novel by Alex Haley from which it was adapted—showed that genealogy was not just a hobby for royalty, the rich elite or academics. Instead, it could celebrate the lives and stories of everyday people.

“[Haley] convinced the world that every family has an important story to tell and that the story is there, somewhere, waiting for every ordinary Gene and Genie to find it,” wrote Elizabeth Shown Mills in a 2003 issue of the National Genealogical Society Quarterly. “Roots” started a revolution, she said—appropriate in a country that had just celebrated its bicentennial.

Haley’s timing couldn’t have been more perfect. That same year, Apple released its transformational Apple II computer, ushering in the age of personal computing. Suddenly, all those budding family historians had access to a growing set of tech tools that would make their research easier. For decades to come, genealogists would adopt new technologies to make discoveries and share them with others.

When asked what makes Family Tree unique, I quote a certain insurance company’s motto: “We know a thing or two because we’ve seen a thing or two.” That’s why I put together this article, which takes a look back at the key moments in modern genealogy history.

Why? Because (as with family history itself), we can better understand where we’re going by reminding ourselves where we’ve been.

1980s and Early 1990s: Personal Computing

Once novelties collected by hobbyists, computers became an important tool that opened another avenue for how genealogists could complete and record research. A host of software made the nuts and bolts of their work more efficient: word processors for typing, spreadsheet-builders for calculating sums and recording data, and early versions of email for communicating.

Specialized tools for genealogists allowed users to build family trees on their computer desktop, boasting features such as source citations and chart exports. Some (like Family Tree Maker, first released in 1989) have stood the test of time.

For decades to come, genealogists would adopt new technologies to make discoveries and share them with others.

Others, such as ROOTS89 (later Ultimate Family Tree) and the FamilySearch Library’s Personal Ancestral File have since been discontinued, but still contributed to making family history research more accessible than ever.

Though the internet was still in its early years, genealogists also gained tools for collaborating with each other. In 1984, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints developed the GEDCOM, a file format specifically for family trees. That made data easier to transfer between programs and people, and GEDCOMs remain the standard today.

Late 1990s: Online Collaboration

Genealogists have long been early adopters of new technology and platforms. Early ways of communicating on the internet (chatrooms, instant-messaging, forums and message boards) were no exception. They flocked to these spaces to share advice, resources and research questions with others who had similar interests.

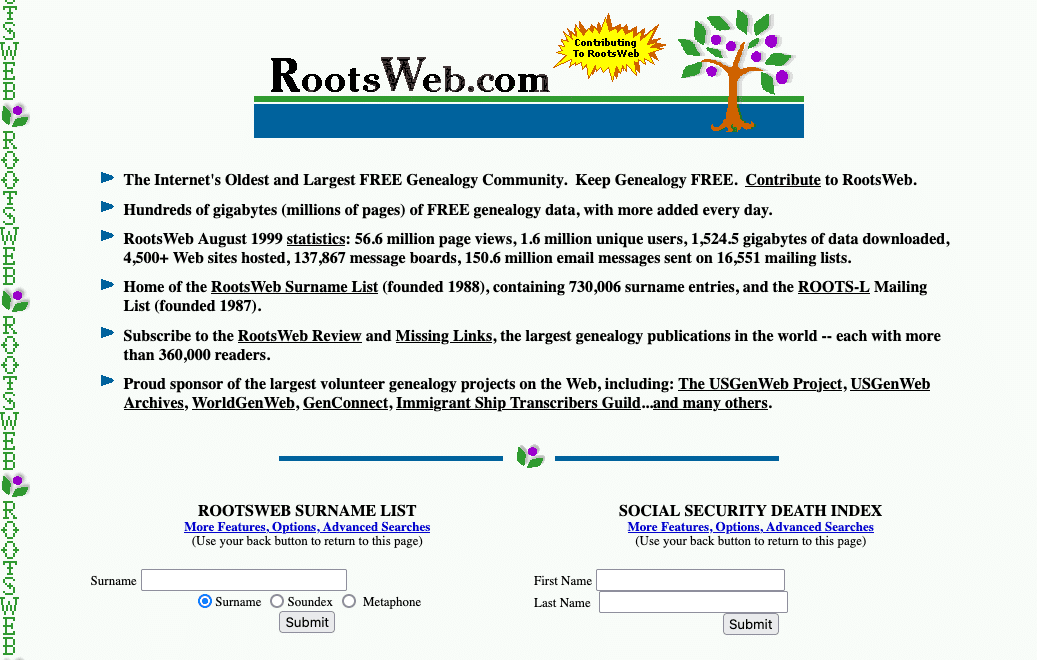

Some of these platforms no longer exist. But other staples of the genealogy community date to this decade—including Cyndi’s List, launched in 1996. Large-scale projects, such as RootsWeb (founded in 1993 and made read-only in 2024) and USGenWeb (1996), leveraged a grassroots network of volunteers to digitize records and connect with other genealogists.

The result was more and more people being drawn to family history. In April 1999, a cover story in Time magazine declared “roots mania,” with genealogy “easy as one, two…tree!”

The next year, we published the first issue of Family Tree—along with our website, which at the time included a search portal where users could enter names and get results from genealogy databases.

The spirit of online collaboration lives on in the many ways that people connect today. Email newsletters and genealogy blogs (pioneered in the late 1990s) continue to deliver news to genealogists.

And though they’re not as popular as they once were, Facebook groups serve as sounding boards for people with similar problems, ancestral places, or surnames. Other platforms, such as YouTube, TikTok and Instagram, allow researchers to tap into expert advice and share their own findings.

2000s: The Growth of Online Records

For as long as there’s been an internet, there have been dedicated historians, archivists and amateur genealogists sharing important record sets online. But the early to mid-2000s saw a sea-change in both the kind of data that could be shared and the ability of people to find it.

Over time, record indexes published in book format gave way first to CD-ROMs, then to text-based webpages. By the middle of the decade, advancements in scanning tech and internet speed allowed for the publication of not just record indexes and abstracts, but images of documents themselves.

This began a seismic change in the way genealogy is done for most people. Researchers no longer had to request records by phone or mail. Nor did they have to commit time and money to visit archives and page through records themselves. “Computers and the Internet … have made genealogy information that once was relegated to a dusty library corner as close as a mouse click,” wrote David A. Fryxell in our inaugural issue.

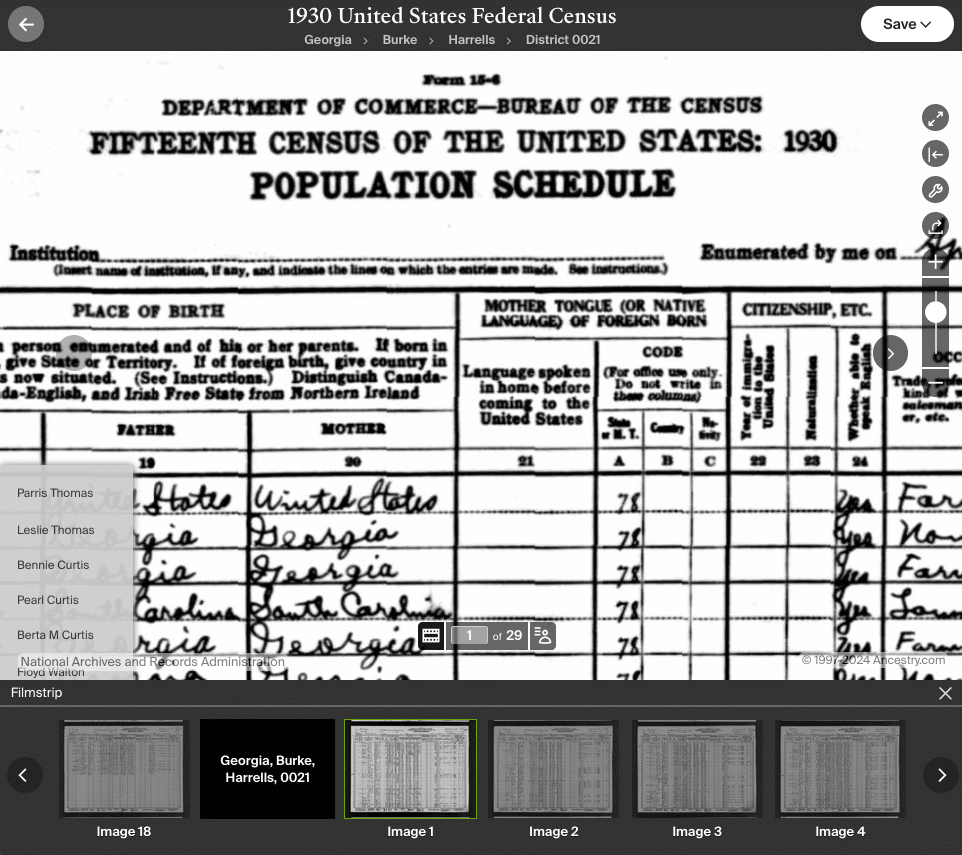

Major releases included Ellis Island passenger lists in 2001. By 2006, images of all the US censuses available to the public at the time had been uploaded to Ancestry.com, another major breakthrough in records access.

In fact, the decennial US federal censuses are an apt case study for how online record access has evolved:

- The 1930 census (released in 2002) was the first to debut as digital images.

- The 1940 census (released in 2012) was made searchable in a matter of months by communities of volunteer indexers.

- The 1950 census (released in 2022) became indexed in just a few weeks, thanks to the combined efforts of indexers and AI tools.

Given that progress, it’s not unreasonable to think the 1960 census (scheduled to be released in 2032) might be searchable at launch.

Other notable milestones included the launch of FamilySearch in May 1999. Now a major hub for genealogists, FamilySearch launched with “just” 390 million searchable names, including the International Genealogical Index for certain regions. The URL for the beta FamilySearch leaked before launch and attracted a staggering 5 million hits per day, and a segment on the “Today Show” with FamilySearch staff caused the new website to crash.

Many records remain offline. But the number of online genealogy records is now well into the billions, with new collections (including from previously inaccessible parts of the world) added every day. In 2021, FamilySearch announced that it had finished digitizing its microfilm, bringing to the forefront a massive trove of additional records.

2010s: The Rise of the Big Four and DNA

Tech companies took notice of these developments and the wide, engaged audience of genealogists. The largest companies today—Ancestry.com, Findmypast and MyHeritage—all originated in the early 2000s. But they became megawebsites by acquiring other, smaller websites throughout the 2010s:

- Ancestry.com: ProGenealogists (2010), Footnote/Fold3 (2010), Archives.com (2012), GeneTree (2012), Find a Grave (2014) and Geneanet (2021)

- Findmypast: Mocavo (2014) and Origins.net (2014)

- MyHeritage: BackUpMyTree (2011), World Vital Records (2011), Geni (2012), Legacy Family Tree (2017) and Filae (2021)

The market grew bigger as the major companies did. Ancestry.com became a publicly traded company in 2009, then sold for $1.6 billion in 2012. (Its most recent sale, in 2020, was for $4.7 billion.) In an oft-quoted article about the 2012 deal, ABC News cited “hobby experts” as proclaiming genealogy to be the second-most-popular US past-time, behind only gardening.

This led to something of a conflict of interest. The resources of large for-profit companies have made documents more accessible than when they were squirreled away in languishing and under-resourced libraries or archives. But they’ve also made genealogists more reliant on the whims of money-making organizations.

The notable exception is FamilySearch, itself a nonprofit. As previously discussed, the organization has kept pace by dipping into its vast stores of microfilmed genealogy records from around the world. And FamilySearch has sought to be a kind of glue that holds the genealogy community together, launching the first RootsTech conference in 2010.

“None of us could have envisioned what we see today,” FamilySearch Chief Genealogical Officer David E. Rencher told Deseret News in 2017. “Who would have thought that a few decades later you would have multibillion-dollar companies in the genealogical space with untold resources.

“All we have tried to do is hang on, partner and work with everybody we can, and be a steadying force in the genealogical community,” Rencher said.

The large genealogy websites have continued to expand their utility beyond simple data-finding. They each boast online family tree-builders, plus the ability to host photos and other images. And they continue to release tools for telling and sharing family stories and (in MyHeritage’s case) editing family photos.

Two of them, Ancestry.com and MyHeritage, also sell DNA tests. That’s no coincidence—the decade also saw a boom in the genetic genealogy industry, led by those companies plus 23andMe and FamilyTreeDNA.

Mitochondrial (mtDNA) and Y-DNA tests had been available to the public for years, but they were expensive, gender-specific and of somewhat limited genealogical use. New autosomal DNA tests—relatively cheap, accessible to both men and women, and able to tell you about both sides of your family—solved all three problems.

Massive marketing budgets and curiosity about “ethnicity estimates” encouraged an unprecedented number of test takers—many of whom hadn’t previously been interested in genealogy. Results made it easier than ever to identify possible relatives, and many of the services developed additional tools to help researchers rebuild family trees.

To date, almost 50 million people have taken DNA tests through one of the major companies. Nearly overnight, genealogists gained a host of valuable new tools.

DNA testing likely reached its peak of popularity in 2018, when law enforcement used popular genetic genealogy website GEDmatch to identify a subject in the long-dormant Golden State Killer case. The high-profile case conveyed both the promise of genetic genealogy and its pitfalls, with many users feeling uneasy about law enforcement’s use of DNA test databases.

Some companies (notably GEDmatch and FamilyTreeDNA) publicly wrestled with the question of whether they’d allow law enforcement to tap user data to find criminals. Others (including Ancestry.com and MyHeritage) doubled-down on their policy of not providing information to investigators.

2020s: TBD

What will the next decade hold for genealogists? In our 50th anniversary issue, how will our editors talk about the upcoming era of family history?

Val D. Greenwood published the fourth edition of The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy (Genealogical Publishing Company) in 2017. In a new chapter on technology, he reflected on the progress the industry had made in the past 17 years since the previous edition of his book.

“If you were to look at the technological resources listed and discussed in the third edition … in the year 2000, you would immediately observe that the list is very unsophisticated from our current perspective. I suspect the innovations yet to come will make our current state of technology also look quite ordinary.”

Val D. Greenwood, The Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy

We can’t predict the future. In fact, we might not even be able to imagine what new technologies will allow us to do. But we can make some educated guesses about what’s around the corner for family historians:

- Artificial intelligence (AI) has captured headlines recently, fueled by tools like ChatGPT. Chatbots, even in their early stages of development, have numerous uses for genealogists. And many existing genealogy tools—such as optical character recognition, image-correction software and DNA matching algorithms—already rely on AI.

- Virtual reality (VR) tools are still novelties. But one day, they could virtually transport us to our ancestors’ times and places. The Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland, completed in 2022, has digitally reconstructed a destroyed archive, allowing users to “walk” the halls and even pull records from shelves.

- Reconstructed family trees have the potential to restore lost genealogies. FamilySearch has developed a collection of computer-generated trees that visualize whole communities based on data in records. And DNA testing services are suggesting familial relationships between test-takers with increasing accuracy.

No matter what the future has in store, we’ll be here to help guide you through every twist and turn.

Then and Now: Genealogy Activities in 2000 Versus 2025

Based on an article by Rick Crume

Sharing family photos

Then: Prints were developed from photo negatives from film cameras, then mailed to family and friends via USPS.

Now: Digital photos can be taken from your smartphone, then shared instantly via text message, social media or email. Family members can collaborate on albums on websites like Facebook, FamilySearch or Flickr. Services like Shutterfly and Snapfish allow you to order photo calendars, albums, mugs, mousepads, posters and more.

Receiving updates

Then: Searches had to be conducted manually each day across various websites.

Now: Users curate feeds, either through social media platforms or using RSS tools or services like Feedly (all of which send push notifications to your mobile device). Google Alerts can send you emails anytime a keyword of interest appears in a new article on the website, as can eBay when a piece of memorabilia goes on sale. Automated record hints at sites like Ancestry.com, FamilySearch and MyHeritage provide suggestions for documents that might match your ancestor of interest.

Translating foreign-language text

Then: Native speakers provide an in-person or by-mail translation for hire.

Now: Text (even whole webpages) can be copy-and-pasted into online translation tools such as Google Translate, or even scanned using a smartphone camera and instantly translated. Professional human translators from around the world can be easily contacted online.

Testing and analyzing DNA

Then: Purchase an expensive DNA test (likely requiring a blood sample) and hope it will one day have genealogical utility.

Now: Buy a DNA test for less than $100, then swab your mouth and mail it in. After a few weeks, you’ll be added to a database with millions of names—some of them potential cousins. Increasingly sophisticated reports suggest how you and other test takers are related to each other and to reference populations around the world.

Building family trees

Then: Fill out family tree forms by hand, or carry around printouts of a software-built tree (or a floppy disk of your family tree file).

Now: Log in to a family tree website from any computer or smart device, or pull up your tree on a mobile app. See billions of family tree profiles created by other genealogists.

Social networking

Then: Find a local genealogy club or society, and attend occasional in-person meetings. Post questions on dedicated forums and chatrooms.

Now: Connect with family historians from around the world using platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram.

Finding books and newspapers

Then: Thumb through paper library catalogs (or call and have a librarian research for you) to determine what publications each of several institutions has. Then page through endless reels of microfilm in the hopes of finding a relevant match.

Now: Keyword-search union catalogs like WorldCat that curate the collections of libraries across the country. Many newspapers, books and record collections are totally searchable online; those that aren’t can often be browsed online or ordered via interlibrary loan.

Tapping FamilySearch’s collections

Then: Visit a FamilySearch Center, then send away for reels of microfilm to scour.

Now: Dive into the FamilySearch Catalog online. View most of their microfilm from home, or travel to a FamilySearch Center or affiliate library to view restricted images; an increasing number of records are also keyword-searchable.

Locating ancestors in vital records, censuses and more

Then: Scroll through microfilm at the library or archive until your eyes glaze over

Now: Type. Click. Done.

Versions of this article appeared in the January 2010 (Crume) and January/February 2025 (Koch) issues of Family Tree Magazine. A similar article by Maureen A. Taylor appeared in the September 2007 issue.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in an affiliate program through Genealogical Publishing Co. It provides a means for this site to earn advertising fees, by advertising and linking to affiliated websites.