Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

A decade is a long time, especially if you measure it in photographs. For 10 years, countless curious family historians have submitted their mystery images for identification in my Photo Detective column and its online counterpart.

Incredibly, pictures continue to pour into my inbox. It seems there’s at least one picture mystery in every family.

Of course, by helping all those Family Tree Magazine readers learn about their roots, I’ve come up with some tried-and-true strategies. These cases are some of my favorites because they epitomize my top 10 photo research tips—clues that can help you identify the people, places and events in your mystery photos.

1. Ask family first.

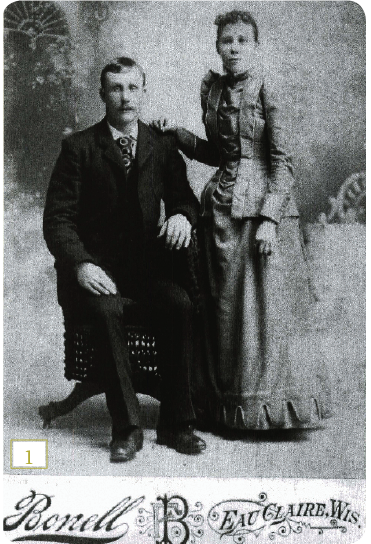

Jackie Hufschmid sent me the very first image featured in an online Photo Detective column. It showed a couple photographed in Eau Claire, Wis. Hufschmid didn’t know their names and couldn’t imagine what her family was doing in Wisconsin. Shortly after it appeared on the then-brand-new Family Tree Magazine website, several people wrote in saying they either owned the same picture or thought the people looked familiar.

But a flurry of e-mails between these folks and Hufschmid didn’t reveal the reason behind this coincidental ownership. The final answer took several years and came from conversations with family members she’d known her whole life. A cousin happened to mention two relatives who’d moved to Eau Claire. In a eureka moment, Hufschmid rushed home and dug out another picture of the couple surrounded by their kids, taken about 20 years after the original portrait. She’d never realized the photo showed the same people—Julia Gullickson and her husband, James Wood.

Family Tree Magazine still gets inquiries about Jackie Hufschmid’s one-time family photo mystery, which originally appeared in our fourth issue of the magazine as well as on our website. Publicity can help you identify an image, but so can clues in the image. Here’s what Taylor pointed out about Hufschmid’s photograph back in August 2000.

- Woman has short, frizzed bangs, popular around 1890.

- Dresses with tight sleeves and high, puffed shoulders were in style only briefly.

- Man’s basic black suit and buttoned vest suggest early 1890s.

- Clothing and other clues date this photograph as circa 1890.

- Imprint reveals photographer’s name and location.

As regular Photo Detective readers know, solving photo mysteries is a process of adding up clues about when a picture was taken and who might be in it. Looking closely at an image to identify the photographic format—such as a paper print, an ambrotype or a tintype—can give you a date range to start with.

The earliest type of photographic image, the daguerreotype, was produced on a reflective metal surface. You need to hold a daguerreotype at a 45-degree angle to view the photo, which is in reverse: a mirror-image of the scene captured on the silver plate. This format was in vogue from 1839 to about 1865, a brief period compared to the longevity of another type of metal image—the tintype. Invented in 1856, these pictures printed on “tin” (actually iron) were popular into the 20th century. Paper prints remained in use from the time of their introduction in the mid-19th century until the digital craze of today.

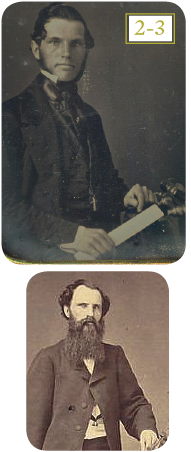

Charles Blyth found this gorgeous daguerreotype (larger photo, left) among other identified family photographs. He wondered if it depicted his great-uncle Henry Blyth, a surveyor who lived in New York State before leaving for Chile in 1853, or one of Henry’s colleagues. The daguerreotype format combined with the clothing style (see tip 5) suggest the photo was taken in the 1850s. Henry Blyth was born in 1831, making him about the right age to be the man shown here.

An identified photo of Blyth taken in 1858 (smaller photo) further convinced me that he’s the man in the daguerreotype.

3. Pay attention to props.

A piece of equipment in Blyth’s photo provided additional evidence. I identified it as a Wye level used for long-distance surveying. That narrows the time frame: If in fact this is Henry Blyth, the image was likely taken before he left for South America.

Several people added their thoughts to the Photo Detective blog post on the Blyth mystery, including a woman who showed the column to her brother, who’s a surveyor. He confirmed the tool is a Wye level and that it was made so “the telescope could be taken out of its mounts, turned 180 degrees, and remounted to be able to check the level bubble and crosshair adjustments while in the field.”

This demonstrates how an object in a photo can be more than a decorative device employed by a photographer to add interest—it can actually deepen the photographic story.

ADVERTISEMENT

Found a name embossed or printed on the front or back of a picture? Most photographers ordered pre-embossed or -printed cards on which they’d then develop photos. The mark is called a photographer’s imprint; it can include just a studio name or also the street address, city and incorporation year. It offers clues to when, where and why an ancestor posed for a portrait.

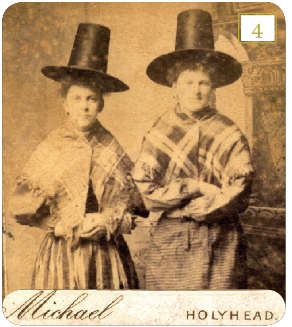

Take, for example, the February 2007 Photo Detective image of two women in unusual hats. The location named in the imprint revealed that “Holyhead” is an island off the coast of Wales with a town of the same name. One of the major industries in the area was rope-making, perhaps an ancestral occupation to look for in other records. You can look up a studio in city directories to trace its address and years in business.

Examine every facet of clothing in a photo from head to toe. Elements of a person’s dress can date an image and even reveal place of origin. For instance, Bill Dodge asked me if one of these young women, each wearing her best dress, could be his paternal grandmother. He found the picture among his father’s belongings.

It’s relatively easy to tell when this image was taken—all the sleeve styles were common in the 1890s. Around 1897, tight lower sleeves with puffy upper sleeves started coming into vogue. But this image also shows evidence of an earlier style in the full sleeves, popular from 1893 to 1896, of the two girls in the back row on the right. To find out whether one of these ladies is his grandmother, Dodge should compare the image to other family photos.

He also thought this might be a graduation photo, because one girl holds what appears to be a nurse’s cap. It’s not, though. If you look closely, you can see that her dress has an uncomfortable-looking high starched collar and attached scarf, which resembles the shape of a nurse’s cap. The ages of these young women means this could be a graduation picture, but if they were nursing school graduates, the girls would be in uniforms with caps on their heads.

Clothes in photos even can provide clues to your ancestral homeland. Browsing clothing history books for costumes similar to those in your photo may result in a match. Though your immigrant ancestor’s everyday clothing depended somewhat on his country of origin, urban dwellers often wore current fashions popular throughout Europe and the United States.

If you find a picture with unfamiliar clothing like the hats in photo 4, you’ll need a special costume guide. Auguste Racinete’s Le Costume Historique, published in 1888 and reprinted in English in 2003 (Taschen), is expensive but useful. Try to locate it in a library. It covers the entire history of costume, most of which predates photography, but the final chapter is a genealogical gem full of color plates illustrating traditional fashions up to 1800.

Another helpful book is Folk Costumes of the World by Robert Harrold (Sterling). The section on Wales describes traditional national attire: a tall black beaver hat with a white frilled bonnet, white blouse with red trim at the cuffs, a bright red underskirt, a checked apron and a shawl. The women in photo 4 are missing some of the pieces, but one wears the checked apron. Both sport the shawl and hat over everyday clothes.

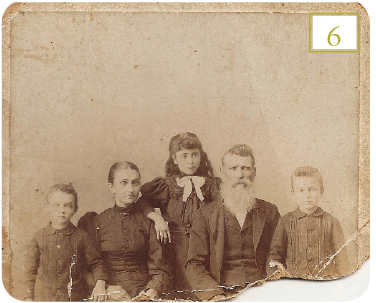

Sometimes the simplest-looking pictures cause the most trouble. This lovely family portrait made my eyes hurt and gave owner Debbie Deaton a headache. Ultimately, genealogical research solved the mystery.

Deaton hoped I could confirm the identities she suspected: Franklin Deaton and his wife, Mahalia Mae Archer Deaton; Mahalia’s son, Harley, from a previous marriage; Arthur Lee Deaton, grandfather of Debbie’s husband; and Zelda.

Deaton knew little about the individuals. Franklin and family lived in Oklahoma, and according to family legend, Mahalia was a full-blooded Cherokee Indian. Franklin worked as a sheriff. He died delivering a tax bill; as he approached the door to a home, the man inside shot him.

I searched subscription site Genealogy Bank for related news articles, but didn’t have any luck. Then I tried the Oklahoma Historical Society website, where you can search newspaper article citations. Again, nothing. Digging a bit further, I searched the federal census using HeritageQuest Online (available through many public libraries). Mahalia showed up in 1900, living with an Archer family. Her relationship to the head of the household is “step daughter;” Mahalia’s children are “step grandchildren.” Both Arthur and “Zildy” appear, but no Harley.

That confused things. The full sleeves on the dresses suggested a time frame of the mid 1890s, but if this picture showed Arthur (born in August 1894) and Zelda (born in January 1900), it certainly wasn’t taken in the mid-1890s. The children were too old, and their ages reversed. The girl in this photo is older than both boys.

With a deadline looming, I published the incomplete investigation on the Photo Detective blog. When I started doing Photo Detective columns, communication from readers was via e-mail. But posting columns on a blog, which launched in 2007, changed that. Now anyone can comment on the images featured in the online column.

An astute reader found more information. According to the Pottawatomie County (Okla.) Genealogy Club website, Mahalia married another time—to a George M. Crow, May 13, 1902. In the 1910 census, Ed Archer has two step-grandchildren, Harley and Jesse Crow. The reader suggested the picture shows Mahalia, George, Harley, Jesse and Zelda. That’s a likely scenario, meaning the photo was taken between 1902, when Mahalia married George, and 1909, when she died. Her clothing is a little old-fashioned for this time frame, but that’s not unusual. Mahalia is buried in the Wanette cemetery in Pottawatomie County.

ADVERTISEMENT

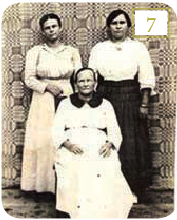

A backdrop could tell you a bit about ancestral hobbies. In my three-part blog series about Helene Armstrong’s photo (above), I noted an overshot-woven blanket in a pattern called Queen Anne’s. Was it created by these women, or did the photographer just think it added character? No one knows for sure, but family papers may reveal the women were displaying their fine workmanship.

To examine miniscule background details, scan the print at a high resolution (600 or more dots per inch) and zoom in on your computer monitor. You also could use a photographer’s loupe to magnify detail. Search for structures, signs, foliage and other clues to the photo’s setting. Don’t forget to look for photographs within a picture: Bureaus, parlor furniture, pianos, walls and room screens in the background might display framed photos of family members.

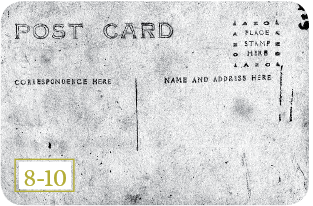

8. Flip it over.

What’s on the back of an image can be as important as what’s on the front. You might find a photographer’s imprint or a handwritten caption there. A tax stamp in the corner would indicate a photo was taken in 1864 or 1865, when the government taxed photographs to raise funds for the Civil War. A stamp box on a real-photo postcard—a photograph with a postcard back, first introduced in 1900—packs an identification wallop. Use the directory at Playle’s auction site to determine when the stamp box design on the back of your photo was in use.

This portrait belonging to Sue Stevenson, for example, is a real-photo postcard with a stamp box common from 1904 to 1918, a date range that threw a wrench in her tentative ID for two of the individuals pictured (see tips 9 and 10 for more on this case). An important note for any captions you find on the back of a picture—or the front, for that matter: Be sure to question the validity of every label. It could be more fiction than fact, written years later by someone who didn’t know the individuals pictured and was guessing at their identities.

9. Look for what doesn’t fit.

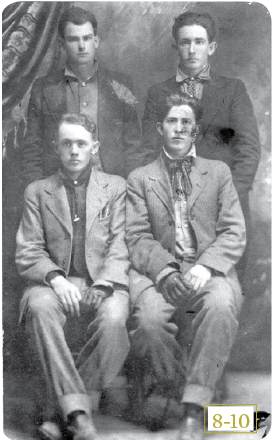

One of the most-viewed Photo Detective pieces was an intriguing postcard image of a group of four men—two of whom, strangely, were each wearing a single glove. And are their pants legs rolled up, or do they just have very wide cuffs? Cuffed pants were common on casual clothes in the early 20th century, but the cuffs on these pants are a bit extreme. Stevenson’s image resulted in four blog postings—the story got better and better.

It’s curious that one man wears a glove on his right hand and the other on his left. I immediately thought, “Could this indicate their dominant hands and that the men wore them for work?” Stevenson was immensely curious about the glove and so were our readers. The second installment focused on their theories, including the possibility the men’s gloves concealed artificial limbs.

According to family stories, the brothers in the family pictured were farmers who made modest livings. One of them wasn’t tall, and instead of having his pants hemmed, he just rolled them up. He also worked as a bronco rider. The glove was employment-related: Bronco riders wear only one glove, on their dominant hand.

The neckties are another interesting clothing detail. One wears a soft polka dot tie, a pattern that first appeared in the late 19th century. The ties, it turns out, are Western in style. The suits combined with the glove suggest this image commemorates a special event such as winning a rodeo.

10. Seek the truth behind family legend.

In the front row, Stevenson’s older relatives had said, were brothers Lance Melson on the left and Elmore Melson (1896-1938) on the right. The men in back were their cousins Samuel Wingfield (born in 1895) and his brother William Garretsmoke Wingfield (born in 1897). The stamp box on the back of this card, as mentioned in tip 8, dates the photo from 1904 to 1918. That means Lance, who was born in 1907, couldn’t be in it. Was this a case of mistaken identity?

Yes. Stevenson discovered her older relatives had slightly misidentified the men. The seated man on the right is actually an older Melson brother, Joel, born in 1894. His 22-year-old brother Elmore, is probably the man seated next to him. (Another brother, Bertram, was born in 1892.) Comparing faces in family photos showed that the Melsons in this photo have the same distinctive ears that show up in other already identified photos. Family research revealed that Joel died of pneumonia in 1918 in Oklahoma. This group portrait was likely the last image taken of him.

Not long after my third blog post about Stevenson’s photo, Denise Damm wrote to me. The Wingfields were her relatives and she had pictures to prove it. It was an online reunion for Stevenson and Damm—now the women are in contact. This picture is a good example of how you need to question everything you find instead of jumping to conclusions. Let the scientific method rule your process. Follow the clues and see what they tell you, rather than trying to make the elements fit what you’ve heard.

All these photos epitomize a mantra of mine: “It’s all about adding up the clues.” Family history, general knowledge, photo format and clothing all expand what you can learn about a picture. Throughout the identification process, you’ll ask questions, research clues and even doubt your sources. When stumped, take another tack.

A decade of images has taught me to never be surprised at the twists and turns in a picture quest. Truth is, you never know where your research is going to take you, but regardless, it’s a fascinating journey. As I’ve learned, putting a name with a face is a lot of work, requiring patience and sometimes, eye drops. Every picture has a story to tell. It’s up to you to let it speak.

From the January 2010 Family Tree Magazine

ADVERTISEMENT