Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Cemeteries are a treasure trove of information for the family genealogist. But before you begin to plan a cemetery trip, you may want to set goals for the journey. It is also helpful to keep in mind some key terms, strategies and general tips for effective and respectful research. Read on to learn more about what it takes to conduct genealogy research in the cemetery.

Setting Goals and Scheduling Appointments

First, decide what you want to accomplish. Is it researching the life of one ancestor or an entire family? Do you need to scan burial records, or would you also like to speak with cemetery personnel? A plan will help you stay on track regardless of what exciting information you uncover.

Next, contact everyone you’d like to talk with. This could include cemetery personnel, funeral home staff, local government offices like the county recorder or township trustees, genealogical societies, historical groups, local libraries and university archives. When setting appointments, you will want to allow enough time to research files, visit the grave and talk with staff.

When you do make contact with these experts, mention your ancestor’s name, birth and death dates, and what kind of information you’re seeking. Many times, relevant records, files and books will be waiting when you arrive, giving you more time to dig into the research and formulate other questions.

Eight Types of Cemeteries You May Encounter

Understanding the different types of cemeteries can be helpful when requesting records. Here are some of the most common types:

1. Public and Municipal

A public cemetery is owned and controlled by a government entity, usually a city, town, county or township. Because it is funded with taxpayer dollars, a public cemetery will by law bury anyone: destitute, suicides and unknowns.

People tend to be buried next to those with whom they have something in common, so look for groupings by religion, occupations, social or class status, or ethnic groups. Cemeteries offer an understanding of local history, including how affluent or poor an area was, how life-changing events like natural disasters or contagious disease outbreaks shaped the area, and who the famous and infamous residents were. The cemetery office and mayor’s office hold the records for these public grounds.

2. Private Cemeteries

Private cemeteries are just that—private. Contact the property owner to gain access. Look for a contact name at the entrance, or call the county assessor, county recorder or land surveyor’s office for ownership information.

The landowner may have the burial records or know where they’re stored. You might also check with funeral homes and genealogical societies. But remember, privacy laws may limit what can be shared.

3. Family and Customary Cemeteries

Family members and in-laws are buried here, along with “customary” neighbors and close friends. This cemetery is usually rural and may be found on the old family homeplace. Unfortunately, many family cemeteries have disappeared. In some states, if the land has been left unattended for a certain time, the county can annex and sell it. Some states require landowners to keep the cemetery up; others do not. Check funeral homes, genealogical societies and historical groups for assistance.

4. Church Graveyards

Church graveyards are some of our oldest organized burial grounds. While plots are reserved for church members, the indigent, suicides, slaves, stillborn and unknowns would be buried outside of consecrated ground. Most of these graves were not marked nor names recorded.

Burial records and additional records of birth, christenings, marriage, baptism and death are in the church office. If the church is closed, check with state and national denominations for records. Also, contact local historical and university archives.

5. Veterans and Military Cemeteries

Military and veterans’ cemeteries come under the jurisdiction of the National Cemetery Association. Currently, there are 155 military cemeteries located in 42 states. Search the national gravesite locator for burial locations.

6. Fraternal and Lodge Cemeteries

Fraternal groups usually sold members insurance centered around death benefits. Groups like Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), Freemasons, Woodmen of the World, and the National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry provided members with a free burial and grave plot in the organization’s cemetery. Modern Woodmen of America (MWA) and Woodmen of the World (WOW) offered free tree-shaped gravestones to members.

Official fraternal records are stored at state and national headquarters. These are private records and member information may not be shared due to privacy laws.

7. Institutional Cemeteries

Institutional burial grounds include orphanages, asylums and hospitals. If remains were never claimed, residents were buried in mass graves, unmarked graves or numbered plots.

When city institutions began closing in the 1990s, properties were sold for development. In rural areas, many were abandoned and left to nature. Check if state or national offices still exist. If not, contact state archives.

8. Paupers Cemeteries (Potter’s Field)

Pauper’s cemeteries are where the poor, unknown or unclaimed are buried. Grave plots and burials are provided for free, usually in public cemeteries. Graves are customarily unmarked unless someone purchased a marker.

Records are seldom complete and may be held at public cemeteries, libraries, university archives or church graveyards.

How to Find a Cemetery

Locating a cemetery can be difficult. Rural cemeteries may no longer exist or be in use. Courthouse personnel can help locate the department that handles records from former and “disappeared” cemeteries.

When searching for the name of the cemetery, look for these records:

Death Certificates

Cemetery names are listed on death certificates and are available from county and city health departments.

Obituaries

Visit local and county newspaper morgues for names and additional information.

County Maps

County maps are useful in finding older cemeteries, family burial grounds and ancestors’ farms. Check the county recorder’s office, local libraries and historical societies for maps.

Land Records and Deeds

Land records and deeds show a direct relationship between family members, neighbors and friends, and indicate who owned the land when the cemetery began. Deed books are usually the only copies of original land deeds and are available at the county courthouse.

Local Government Offices

If a cemetery does not have an office, visit City Hall and request the “Map of Burials” for a burial ground.

Local Funeral Homes

Funeral homes can pinpoint where old or forgotten cemeteries are. Check their files for obits, memorial cards, death write-ups, funeral guest lists and stone carvers.

Post Offices

Post offices know what street names have changed and where former churches, funeral homes and cemeteries were located.

GPS (Global Positioning System)

GPS can pinpoint exact cemetery locations and a grave’s location. BillionGraves.com and FindaGrave.com both use GPS coordinates in their databases.

Enter the cemetery name into a Google search. If you’re in the area, type in “cemeteries nearby” and see what pops up on the interactive map.

What if the Cemetery Has Been Moved?

A cemetery may be relocated due to a road project or state use of the land. Records should list the graves moved and where to. For church graveyards, the original cemetery will remain at the first location, while a new cemetery is located adjacent to the “new” church.

Historical societies, libraries, funeral homes, county histories, city or town directories, and newspapers may contain stories and records of the move.

Seven Cemetery Records to Review

Below are some cemetery records that you might find useful as you research.

1. Registry of Burials (Sexton’s Records)

Older “cemetery books” contain three main types of records:

a. Burial records in chronological order

b. Maps that show where the grave is

c. Cemetery deeds with purchasing information

These records may be in a book or ledger or filed as loose papers. Burial records always include the deceased’s name and date of burial. Also, look for the plot owner’s name, the amount paid and who used the plot, or it was resold.

2. Cemetery Deed

A cemetery deed is a deed to the property. The original is given to the real estate owner while the cemetery gets a copy for its files. The sale is recorded in the city or county recorder’s office. The deed includes a physical description with size and dimensions, name and address of purchaser and seller, amount paid, plot number and cemetery name.

3. Funeral Records

Funeral records are created by the undertaker and focus on the funeral and burial, including who ordered the service and their relationship to the deceased. Look for spouse and parental names, time and date of the funeral or burial service, type of burial container, and what the deceased wore.

4. Burial Permits

This legal document allows the remains to be buried or interred. Completed by the funeral director or embalmer, a death certificate may be included. The burial permit always includes the name of the deceased and date of death. Look for the deceased’s last address, burial date, cemetery section and plot number, and name of the informant and relationship to the deceased. Burial permits are issued by a state’s local board of health or town clerk.

5. Plot Records

Plot records give the physical location of a grave, lot number and visual description of the plot. The deed number, plot owner’s name, purchase date, amount paid and name of interred may be included. Plot Records are in the “lot” or “plot” book.

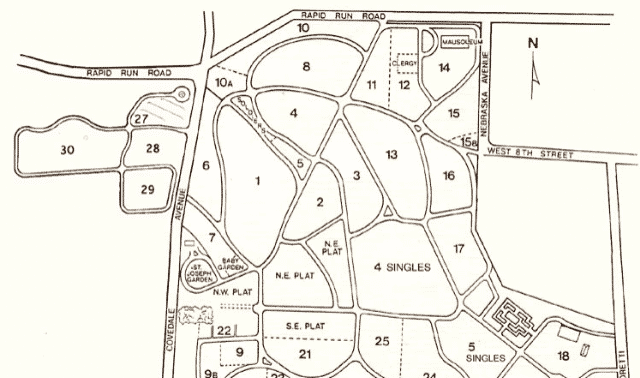

6. Plat Maps

Plat maps show the actual layout of the cemetery grounds with graves. The plat book lists section names, location numbers, burial row numbers and grave or plot numbers.

7. Grave Opening and Closing Orders

These official orders allow the gravedigger to dig a grave and fill it in. Records list name, gender and age, date and place of death. The burial location, plot number and name of the undertaker or funeral home may also be mentioned.

What to Do When You Reach the Cemetery

When you arrive at the cemetery, start taking photos by shooting the entrance and any signs. Drive or walk through to get your bearings and establish a feel for the community.

Visit the office and look for relevant materials—a book or pamphlet about the cemetery’s history, plat maps and famous burials. Ask about local stories around the time of your ancestor’s life and see if any special records exist.

A cemetery Sexton, in the late 1800s, documented every burial by listing the weather, names of pallbearers and those who attended. He always ended his notations with “May You Rest in Peace.” (Personable and touching.)

What to Do When You Reach the Grave

Take a few moments to stand at your ancestor’s grave and experience being here. When you’re ready, begin by taking photos of the stone. Shoot it from all angles; above, low and straight-on, and front, back and sides. If the inscription is hard to read, water can bring out the letters or your phone’s flashlight can help define the lettering. Zoom in on the inscription and note unusual markings or symbols. Ask cemetery personnel about meanings or if the headstone order form still exists.

Now, take photos of all the surrounding graves. These pictures may be helpful for cluster research because our ancestors were usually buried with family, in-laws, church members, workmates and neighbors. Finish with a wide shot of the burial grounds.

Cemetery Versus Graveyard: Which Term to Use?

As you research your family history, you will want to make sure that you understand some key terms, especially as you connect with others. Cemetery and graveyard are two such terms. The term “cemetery” and “graveyard” are used interchangeably, but there is a difference.

Cemeteries may be supported by public taxes. Public grounds are usually well-maintained, and the office has detailed records. A cemetery has no connection to a specific faith or place of worship.

A graveyard refers to burials made on church property. Those buried here likely attended the adjacent church. Graveyards are modest compared to public cemeteries. Burial rows may appear haphazard instead of in defined lines. The types or sizes of headstones may be restricted, and burial records may not be organized.

Pulling It All Together

Once home, upload your photos and forms into folders and label them. Check the new information against research you’ve already done. Do a thorough investigation into abbreviations and symbols on the gravestone. Use photo editing software to bring out hard-to-read lettering and inscriptions. Once you’ve assessed the findings, add reports, forms and photos to your family tree software and online tree.

And don’t forget to send emails thanking the folks who helped you. A little kindness goes a long way in uncovering your family’s history.

Related Reads

Last updated: October 2022