Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Q: What is endogamy and how can I overcome it?

A: Endogamy is the process of marriage within the same group of people over and over and over again. Jewish, Acadian and island populations (including Ireland) are all good examples of endogamous groups, as are many small insular towns where residents lived for generations.

First, let’s be clear: You cannot “overcome” endogamy any more than you can overcome an inherited cleft chin or curly hair. It’s here to stay. But like the curly hair, there are techniques you can learn to manage (and make the most of) your endogamous heritage and harness the power of DNA in your family history.

You’ll encounter two main problems when applying DNA to endogamous groups: the amount of shared DNA you have with matches not accurately reflecting genealogical relationships, and the resulting difficulty in sorting and grouping matches. Both have workarounds.

Problem 1: Using Shared DNA to Determine Relationships

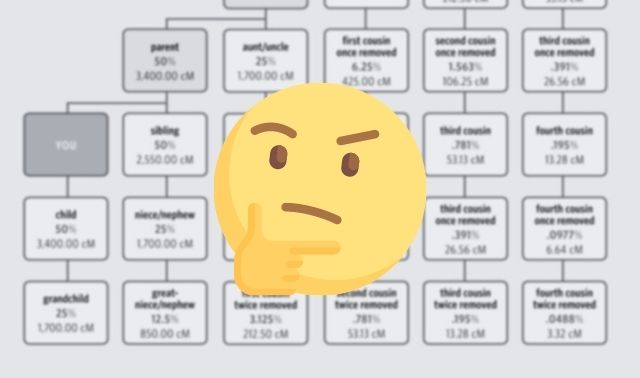

DNA relationships are measured in centimorgans (cMs), and DNA matches are presented to you alongside a shared-cM value. That constitutes your genetic relationship with a DNA match, which you can use to determine a corresponding genealogical relationship.

The same genetic relationship can often result in multiple genealogical relationships, however. Based only on shared DNA, you and a DNA match could be related in one of multiple ways. For example, you and a match who shares 100 cM could be third cousins, second cousins once removed, half-second cousins, and so on. You’ll need to conduct more-traditional genealogical research to determine which is correct.

Endogamy makes this even more complicated. Because of generations of intermarriage in endogamous communities, you’ll often share more DNA with a relative than you normally would. For example, third cousins usually share about 75 cMs. But if you have endogamous roots, that same third cousin might share 250 cMs with you; that would normally put them in the second-cousin range. To sum up: Endogamy makes genetic relationships look closer than they should be.

The Workaround: If your testing company offers a chromosome browser, use it to count shared segments of DNA that are longer than 15 cM. Then, include only those long segments in your total when calculating a relationship using shared DNA.

Problem 2: Grouping Matches

In a similar way, endogamy presents challenges when trying to sort your DNA matches by family group. Many popular techniques rely on family lines being genetically distinct from each other. If yours aren’t distinct, these grouping techniques won’t work for you.

The Workaround: Instead of trying to isolate matches by family line, focus on your best matches as measured by the largest longest segment. These are the most worthy of your time.

If you want to learn more about using DNA in your endogamy research, you can join my “Endogamy & DNA” class.

Related Reads

A version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: June 2025