German can be tricky for non-native speakers, and it’s easy for words to become lost in translation. This was the case when I was trying to visit an ancestor’s hometown: the tiny village of Elsoff, now part of the German Land (state) Nordrhein-Westfalen.

During my first two trips to Germany, I queried my hosts about going to Elsoff, only to be told it was too far. My map told me different. But not wanting to be the stereotypical “ugly American,” I didn’t press the issue.

Later, I mentioned Elsoff in an email. Seeing the name in print must have made up for my terrible German accent, because the hostess told me that when I asked about the town, she thought I said Elsass, the German name for Alsace, when I was actually trying to say Elsoff. Alsace, now part of France, would’ve indeed been quite a distance from my hosts’ home. No better evidence than this has shown me how easily German names and places can become garbled and misunderstood.

That’s why it’s important to learn about the language your German ancestors spoke. In this article adapted from my book, Trace Your German Roots Online, we’ll cover easy-to-use online tools that help you “ungarble” German personal and place names.

Some of these resources deal with surnames and phonetics, while others offer map and gazetteer resources. They’ll help you find the names of your German-speaking ancestors and the places they lived—the keys you need to dig further back into your family history.

Understanding German Phonetics

Only a foolish person immediately says “But my ancestor’s name wasn’t spelled that way” when confronted with a record that uses a different spelling from what the researcher is accustomed to. When you consider the many dialects of German used in Europe—and that many American records were created by English-speaking clerks, enumerators or tax collectors—well, that’s a recipe for a smorgasbord of place and surname spellings in the records you’ll find.

The short course in German phonetics (there’s a longer version in The Family Tree German Genealogy Guide) is that several consonants frequently are interchangeable: the b and p; d and t and th; g and k and c; and (because of pronunciation differences) the German w and the English v.

For more on the German language, see my other article.

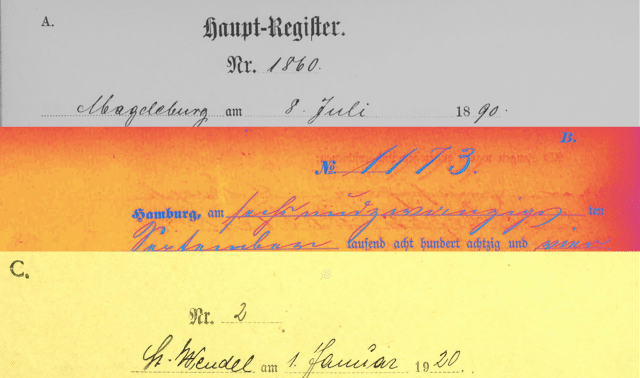

The German umlaut and “double S”

For vowels, the number-one source of confusion is the German umlaut. An umlaut, generally written as a pair of dots over the vowels a, o, u and y (the last usually appearing only in the Swiss German dialect), affects the pronunciation of the vowel. The use of umlauts is a shortcut for putting an e after the vowel. You may see a surname or place name Americanized either without the umlaut, or without the umlaut and an e added: Klöckner might become Klockner or Kloeckner.

Another German-language peculiarity: A “double s” is frequently represented as an Eszett, which looks like ß and is rendered much like (and often mistaken for) a Roman script uppercase B. The surname Thoss—Thoß in German—might be transcribed as Thob or even Thop.

Think in terms of spelling variants

Whenever you encounter a new German surname or place-name in your genealogy research, think about it not in terms of the spelling but rather as a set of spelling variants, using phonetics to flesh out the universe of possibilities for the name.

This is especially true for new-to-you place names, particularly if you don’t immediately find them on a map (or you’re unsure whether you’ve indeed found the right town). Jot down a list of possible spelling variants so you’re attuned to all possibilities when searching databases for records or browsing through documents.

For a quick-and-dirty recap of how letters are pronounced in German, use ThoughtCo.com’s German Phonetic Spelling Code. While this is primarily a code used for spelling out letters for use in broadcasts, it gives the basic sounds that will help you with German in general, too.

Getting around Language Barriers

Websites for German genealogy will essentially fit into one of three categories: written in English, written in German and requiring translation, or written in German with an English version of the site.

Combine this with the fact that many of the records you’ll be accessing are handwritten or printed in German, and you face a potential linguistic roadblock. You can circumvent this obstacle by improving your German language skills or your skill at finding translation resources.

Translation resources

When confronted with language barriers, translation resources are key. First, try Google Translate, which lets you translate a word, phrase or passage from German to English (or between any of the hundreds of other languages available).

Google Translate, however, gives translations that are rough at times and fail to account for many contexts. You may want to double-check Google’s translation on other translation websites such as BabelFish. Online German-English dictionaries, such as BEOLINGUS, Dict.cc and Linguee also can provide valuable translations for words you’ll likely find during research.

If you’d rather take translation matters into your own hands, the web offers a variety of services to teach yourself German. Some of these apps, podcasts, articles, courses and sites include:

- Deutsche Welle: free online course as well as a free podcast called the DeutschTrainer

- Duolingo: free iOS and Android app

- Learn German by Podcast: free podcast

- Mango Languages: free iOS and Android app

- National Institute for Genealogical Studies: online course

- Slow German: free podcast

If you’re interested in learning the German language so you don’t need to rely on translations, Study in Germany is an excellent resource. This is a step-by-step guide that was created with one goal in mind: To help complete beginners learn how to speak German fast.

Online Tools for German Surnames

In addition to trying out phonetic variants of surnames, some online tools let you get an idea of where those surnames are found in today’s Germany. While there’s no guarantee that the highest concentrations of a surname in modern Germany will be an exact match of those names’ historical concentrations, these databases do give you a starting point for a geographic hypothesis on your family origins when other records haven’t borne fruit.

The Geogen Surname Mapping site, generates three types of data on surnames:

- relative distribution: gives the number of instances of the surname per million phone book entries, which adjusts for the potential of a lot of instances of a surname purely because of an area’s population

- absolute distribution: puts the actual numbers of entries into groups

- pie chart: shows the percentages in which the surname is found in current German states

To begin searching Geogen, call up the site and type the surname you’re interested in into the box (for example, Rathmacher). You’ll see a pie chart, plus maps indicating both how many people have that surname in each part of Germany and how many there are relative to the whole population.

Select the Links tab to see a number of potential spelling variants and the number of entries for each. In addition, this tab offers maps of the surname in other European countries and the United States, as well as other web links. Note that the site may not work in all web browsers. If you have difficulty using it, try another browser.

Including Historical Maps

Because of the many changes to political divisions in German lands, you must always think about your ancestors’ hometown not only in terms of where places and boundaries are now, but also in terms of “then”—with “then” possibly referring to multiple time periods.

A number of websites will help you bridge this gap between today and yesterday, hopefully leaving you with no town unfound. Some have actual maps; others are gazetteers (essentially, encyclopedias of places).

Online resources for German historical maps

A good tool is Meyers Gazetteer of the German Empire, which is also called Meyers orts– (short for the German Meyers Orts- und Verkehrs-Lexikon des Deutschen Reichs) and is searchable on Ancestry.com. Compiled in 1912, this resource lists the type of place (town, community, etc.), state, population and more for parts of Germany lost to neighboring countries after World War I. It’s in German gothic script and contains abbreviations; Ancestry.com’s database information and the abbreviation table can help you use it. It provides the map coordinates, jurisdictional information, foreign or former names and other details about the towns, parishes and other places you search for.

But as far as historical maps go, among the most-detailed and accessible is Atlas des Deutsche Reichs (Atlas of the German Kingdom) by Ludwig Ravenstein, published in 1883. Once you find a village in Ravenstein’s atlas, you can compare the area to a modern-day map. You’ll likely want to begin using the atlas by keyword searching, so go to Search Within Text. In the search box, enter the name of your ancestors’ village.

If you can’t find information on your town (or you want to manually browse the atlas’ pages), return to the atlas’ home page and click Browse the Atlas. On the resulting browse page, choose one of the sections of the map, labeled Ia (northwest Germany) through Ix (southeast). Then click the thumbnail image to load a PDF of the map in your browser (or right-click on a PC or control-click on a Mac to download the file). You can zoom in and out and pan around to find the town. Note the names of nearby towns and the state or province.

Another site worth mentioning is Kartenmeister, a comprehensive database for villages in the former eastern Prussian areas, which now lie mostly in Poland.

For maps of modern Germany, you can try using Google Maps, although there’s a caveat: Even if the name you type applies to multiple towns, the engine will find one village with that name while ignoring the others. A workaround is to search for neighboring villages instead, if you know any. The German National Tourist Board has a variety of maps among its arsenal of resources. But the best online modern-day maps are served up at ViaMichelin.

With all these language and geography resources, you probably feel like a race car driver waiting for the green flag to take off. Understanding some basics about your ancestors’ language and hometown is the first step in journeying to the old country. So, Damen und Herren: Start your engines.

Related Reads

A version of this article appeared in the March/April 2016 issue of Family Tree Magazine. Last updated: April 2025.

FamilyTreeMagazine.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.