Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

It’s so easy to focus on just the faces and clothing that are prominently featured in your family photos, letting the other details fade into the background. But right there in plain view are clues you might be missing, clues that can help you determine when and where a photo was taken, identify who’s in it, and understand something about that person. These subtle details are in the jewelry your ancestors wore; in possessions such as cars and cameras; and in the backdrops, foliage and furniture behind them.

Take, for example, the eight photos featured below. Their “hidden clues”—and what those clues say about each image—will help you take in new details in your own old pictures.

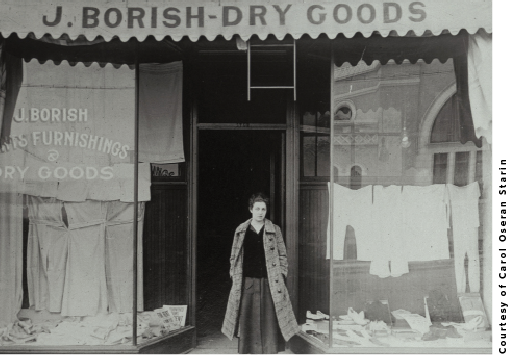

1. Reflections

Anna Borish, born in 1897 in Bessarabia, stands in front of her father’s store in Seattle (about 1912). Her descendant Carol Oseran Starin found the store’s address in a city directory. Looking closely at the reflection in the store window on the right, Starin was surprised to see a building she recognized. This clue pinpointed the exact location of the store across the street from Bikur Cholim Synagogue, a place central to the family’s life, in Seattle’s Yesler neighborhood.

Check your photos for reflections in windows, mirrors and picture frames. Even if your photo doesn’t have these things, look for a business name, street sign or noteworthy building, which you can look up in city directories. For more information on using these directories, see our guide. If you know generally where the picture was taken, you may be able to use the free Google Earth to “walk” down the street and locate the buildings. Genealogy Gems’ Lisa Louise Cooke of offers a free video demo of Google Earth.

A street itself is another clue. Many local histories mention when improvements such as paving and street lamps occurred, as do town or city annual reports. Local papers also might report on these updates. Telegraph lines, railroad tracks, fire hydrants and bridges are similar clues.

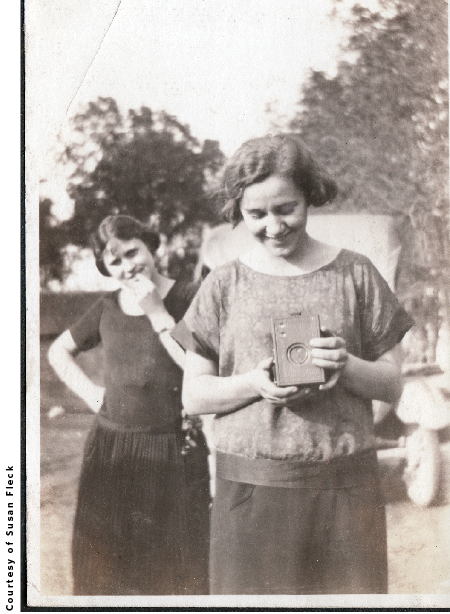

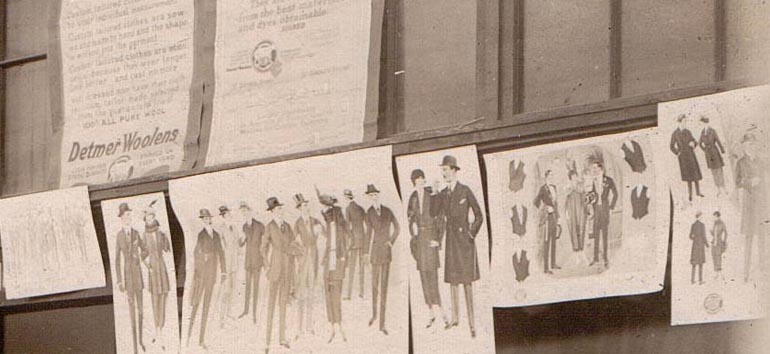

2. Technology

Susan Fleck’s grandmother Opal Marguerite Hoffman Jackson holds a box camera in this photo. The appearance in a photo of cameras and other dateable gadgets—typewriters, binoculars, bicycles, etc.—can help you determine the beginning of your date range for when the picture was taken. Of course, a family might have held onto these items for years, so look at all the photo clues together as a whole.

Running a Google search such as bicycle history can tell you when a gadget was commercially available. Compare the item in your photo to image search results, too. Jackson’s camera is a Kodak Brownie, available from 1901 to 1935 in a variety of models. This camera closely resembles the Brownies produced during the early 1920s, when Jackson was a college student. These dates agree with the clues in the style of hair and clothing the young women wear. In addition to a date, this camera provides a clue to Jackson’s hobbies.

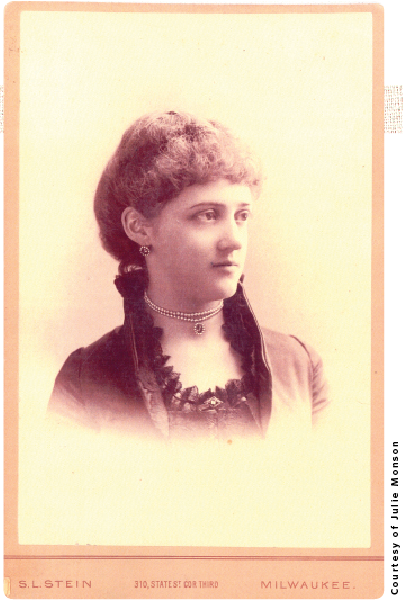

3. Jewelry

Julie Monson’s great-grandmother Adelaide Louise Sanderson donned a fashionable pearl choker necklace to sit for her portrait in Milwaukee. Chokers became fashionable in the late 1800s after Alexandra, Princess of Wales, began wearing them, purportedly to conceal a scar on her neck. The style of this one, as well as the high collar on Sanderson’s dress and her curled bangs, support an estimated 1884 date for the picture.

An earring or pin may seem like a tiny part of your picture puzzle, but changing trends in jewelry can help you date an image. In the 1850s, well-dressed women pinned hair jewelry to their coiffures. In the 1860s, brooches worn at the collar were popular. Heavy-looking chains and crosses were stylish in the 1870s. Men and women of the 1880s wore fanciful collar and lapels pins. By 1900, watches were common on women’s bodices. Compare jewelry in your photos to the pictures in Dressed for the Photographer by Joan Severa (Kent State University Press) and 20th Century Jewelry: The Complete Sourcebook by John Peacock (Thames & Hudson).

Small accessories can open up new research avenues. A lapel pin or tie clip might feature fraternal order insignia (three interconnected rings, for example, is the symbol for the International Order of Odd Fellows) or military organization, such as the Grand Army of the Republic. If you’re unsure which side of the family a photo belongs to, expensive jewels could point you to a prosperous branch. Ask relatives about any inherited jewelry that may match what’s in a photo.

Jewelry might even hold a photo within your photo. Beginning in the 1840s, pins, lockets, rings, cufflinks, bracelets, keywinds (used to wind watches) and coat buttons with photos provided a way to include a deceased or absent loved one in the picture. Get a closer look at the image by scanning the photo at a high resolution and zooming in.

4. Vegetation

Trees, shrubs and flowers might not date a photo to a specific year, but they’re often overlooked as a seasonal clue and a part of a photo’s story. Marilyn Dunning’s great-granduncle Pieter Willemszoon Schagen (1850-1944) with his wife and daughters, posed in their Paterson, NJ, backyard. Clinging to the arbor behind Schagen’s head is a vine in full foliage, telling us the photo was taken midsummer. Bare trees, of course, would mean late fall through early spring. You sometimes can use this type of detail with clothing clues and genealogical records to narrow a date of birth—for example, a baby who appears 6 months old in a summer photo was probably born in late winter.

Take geography into account when looking at foliage clues. Spring’s daffodils and tulips bloom later the further north you go. Consult gardening guides and historical weather resources (such as the the Old Farmer’s Almanac) for information on growing seasons where and when your ancestors lived. Notice what doesn’t fit, too: If your family lived in Vermont and they’re photographed among tropical plants, they may have been on a trip.

If you’re not a master gardener, use a field guide to figure out what kind of foliage you’re looking at. You also might find help from a local garden club. Note that not all plants visible in an old picture are necessarily still common in home gardens. Many species are extinct or have changed through breeding. The Victory Seed Co.online catalog can help you identify heirloom varieties.

Pictures with plants can inspire oral history questions. It’s possible, for example, that Schagen’s garden was a point of pride. It might be a war-era Victory Garden. At the least, it indicated someone in the family had a green thumb.

5. Backgrounds

What’s behind your relative in a photo could add to its story. In this image, for example, Helene Armstrong’s great-grandmother Margaret E. Jordan Stephens (seated) posed with two other women in front of a bed covering. This blanket, though, is more than a way to hide an unattractive background. When I first blogged about the photo below in 2007, a reader knowledgeable in textile arts explained this is a woven coverlet, either machine- or handmade.

Notice behind the shoulders of the women standing, where the vertical columns of darker squares are misaligned? That’s where two pieces, woven on narrow looms, were sewn together to create the necessary width. As for quilts, woven coverlets might follow patterns characteristic of a place or time period—or the artist might have come up with her own pattern. A guide such as A Handweaver’s Pattern Book, revised edition, by Marguerite Porter Davison (Churchill & Dunn) could help date this pattern.

Georgia women have a long tradition of producing beautiful textiles. One or all of these women may have made the blanket. Clues in Armstrong’s family history might reveal whether anyone worked with textiles. On the other hand, the blanket might’ve been the photographer’s. Itinerant photographers usually hung a plain white backdrop, but sometimes they used whatever was handy.

Your photos may display other types of clue-filled backdrops. Beginning in the 1840s, studio photographers employed artists to paint theatrical-style backdrops depicting parlors or local scenes. Photographers would sometimes enhance the setting with real props, such as picket fences or bicycles. Midwestern ancestors posed in front of a seaside backdrop might indicate a vacation or migration.

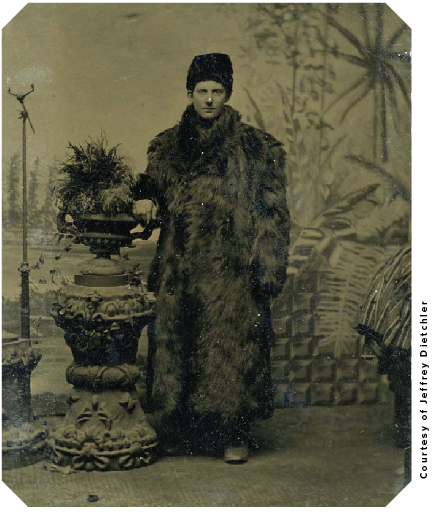

6. Furniture and Props

Sitting for a portrait required our ancestors to hold a pose, sometimes for several minutes. Furniture, supports and braces aided them, as you can see in Jeffrey Deitchler’s picture. The subject leans on a potted urn—a common posing device around 1880—and an adjustable metal brace with a clamp stands unused, off to the side. Information from Deitchler’s research will help narrow the time frame.

Each decade saw different devices employed to help the studio capture a perfect portrait. In daguerreotypes from the 1840s and 1850s, you’ll see arms resting on tables. Columns for leaning on became common in the 1860s. If you look closely at pictures from the 1860s and 1870s, you often can spot a wooden X behind the subjects’ feet. That’s the base of a brace. Deitchler’s tintype was likely meant to be inserted in a mount, which would crop the brace out of the scene.

Posing chairs, available as early as 1864, proliferate in images later that decade. Some look like dining chairs with high backs and curved wood arms; others were designed especially for photography studios. Fringed chairs became popular starting in the mid-1860s. In the 1870s, women would fold their arms and stand in profile, resting against rolled-back upholstered furniture, to show off their dresses with large bustles. Faux fences became common for support and decoration in the 1880s. In the 1890s and early 20th century, you’ll often see pale-colored wicker chairs and animal skin rugs. Furniture history books, such as Field Guide to American Antique Furniture by Joseph T. Butler (Henry Holt and Co.) can familiarize you with popular furniture designs over time. Because studios would keep equipment for several years, look at these items in the context of other clues.

7. Cars

Early in the 20th century, cars evolved from resembling horseless carriages to the vehicles we recognize today. Linda Lemon’s great-grandfather Peter Riess, from Bronx, NY, posed in this car around the turn of the century. According to Lemon, his first car was an 1898 Winton. Is this the same car?

Dating a photo based on a car is tricky. Our ancestors didn’t upgrade to a new model every year, plus there was a lot of variety: In 1900, Americans owned only 8,000 cars, but close to 200 manufacturers operated in the United States.

There’s no comprehensive guide to all the makes and models, but paying attention to a car’s details—lights, running boards, tires, chassis and decorative elements—can help you identify it and determine when it was sold. That gives you a start date for the photo. Riess’ car, for example, has headlights and a center headlamp on the front bumper. If you search Google images for Winton automobiles 1898, you’ll see that this vehicle shares features of early Winton models, but lacks the convertible top. In this image, you can see the crank starter in front of the rear wheel. The hand-operated brake is on the outside of the driver’s door. Early cars like this one lacked windshields. Some carmakers had begun replacing the steering tiller, which Reiss’ car features, with a steering wheel, but that change wasn’t complete until about 1910. Also watch for the length of the chassis. In the 1930s, long, sleek automobiles were fashionable, but early cars were short and somewhat boxy. These clues support what Lemon has determined about the photo.

Compare automobiles in your family photos to those online by searching online for a make, model and time frame. If you don’t know those details, you can uploading the image to Google Images (just drag the image file onto the search box) to see if there’s a match. Also check car collector magazines like Hemmings Motor Newsand Classic Car.

A license plate on a car can help you estimate when the picture was taken based on license plate laws and designs, and even find out who owned the vehicle. New York required plates as of 1901, but the owners of the cars created them. In 1903, Massachusetts was the first state to produce official license plates. Some states, like Rhode Island, published booklets of license plate numbers and the name of the person to whom they were assigned.

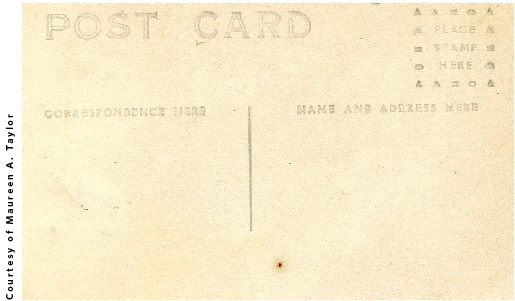

8. Stamps, Stamp Boxes, and Labels

Our final clue is hidden on the back of a photo: Starting in the early 20th century, our relatives could have photos developed with a postcard back, suitable for mailing. The design of the back, particularly the stamp box, can date the image on the front. The divided design, with separate areas for address and message, and style of the stamp box on this postcard dates it to after 1907. March 1, 1907, it became legal to include both the address and a message on the back of a postcard. AZO was a popular manufacturer of photo paper.

The Playle auction website has a directory of stamp box designs and the dates they were used. They’re organized by the first letter of the paper manufacturer’s name (AZO, for example, produced the paper this photo was printed on).

Picture clues can be tiny, visible only by enlarging an image, or they can dominate your photo. If you’re having trouble identifying a mystery photo or understanding the story of its people and places, try to see it with fresh eyes—or have a friend or relative take a look. Details you’ve been overlooking might become obvious. Then you can follow the pictorial bread crumbs to a new family history discovery.

Tip: Have a friend look at your stubborn mystery photos. Sometimes a person viewing a photo with fresh eyes will pick up on clues you’ve missed.

From the May/June 2015 Family Tree Magazine