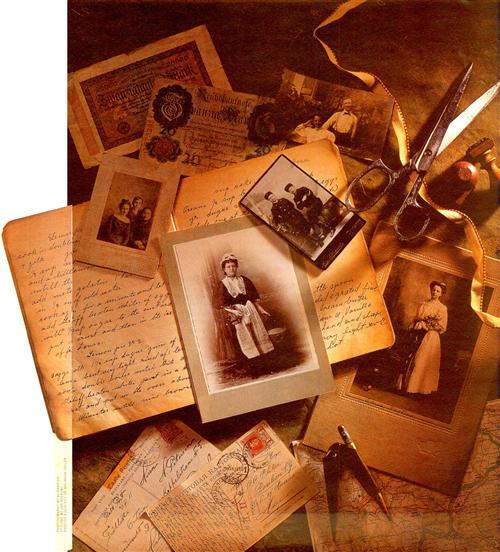

Photographs of immigrant ancestors can tell you more than just what they looked like (“so that’s where Aunt Edna got her nose!”) — they often contain evidence of an ancestor’s origins and migratory paths. Because immigrant images show unfamiliar scenes and include words in another language, they are often ignored or misunderstood. It’s time to rediscover them, because a single photograph can unlock your family history.

Even if you don’t have any images in your home collection, try to find photographs when you do your research. Discovering your family roots in the old country helps you reconnect with relatives and possibly new material and additional photographs. One researcher I know found long-lost cousins in the town her family came from, along with new sources for genealogical data, all because of a single photographic postcard.

Researching photographs, particularly those with foreign connections, is challenging and takes time, but pays off. For instance, if your family came from a non-English-speaking country, you’ll need to translate any written or printed data on the image. Be observant. Often the date is in the little details in the picture. Find out as much as you can about the oral history of the image in your possession. You can also use the tips outlined in “Picture Puzzles” in the August 2000 Family Tree Magazine.

Start evaluating why an image is important to your family by asking:

• Who or what is the subject of the photo?

• Are there stories associated with it?

• How did it end up in your collection?

The answer to the last question may provide the most helpful information. Museum curators talk about the provenance of an object, meaning the history of ownership. As the family “curator,” you need to find out more about who owned an image in order to interpret the evidence in an immigrant photograph. Many immigrant images document the family before they left the old country. A chart of ownership will make it clear who left home and who stayed behind.

Deciphering a photo’s “signature”

After investigating the basic questions regarding a particular image, it’s time to begin reading the clues — starting with who took the picture. Photographers often “signed” their works by placing their unique imprints somewhere on or around the image. Since the majority of photographs are paper prints, look on the front of the cardboard mount, the back of the image or the lower right corner of some images. Imprints include the photographer’s surname and sometimes business location.

Most likely, foreign imprints will require some translation. If you’re unfamiliar with the language, consult a special dictionary or an online translation service to help you read the imprint. Even if the locality appears in an alphabet you can read, it may still need translating. Copenhagen, for instance, can appear as Kjøbenhavn in the imprint.

The real challenge is actually finding the place in an atlas or gazetteer. Political upheavals changed country boundaries and wars eliminated many small towns. A historical atlas can help place the photograph in context. On the Web, try the Global Gazetteer, the Geographic Names Database or the Library of Congress’ Map Collections: 1500-1999 to search for town names.

Discovering when and where the photographer operated his business can tell you about your family. Immigrants usually frequented photographers who lived in their community and often came from the same background. City directories provide dates when a photographer was in business and census documents can fill in personal details. Directories of photographers also exist. Try searching the online database of photographers at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House or find a regional directory and research tips in Peter Palmquist’s Photographers: A Sourcebook for Historical Research (Carl Mautz Publishing, $40). For resources available overseas, check out the World Gen Web site for a particular country. Also helpful are the guides published by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for conducting country-specific research, available in print or online at FamilySearch.

Another online option is to use the search engines offered by Genealogy.com and Ancestry.com or even a non-genealogy, general search engine such as Google. You might get lucky and come across information about a photographer on a family Web page or in a history of photography.

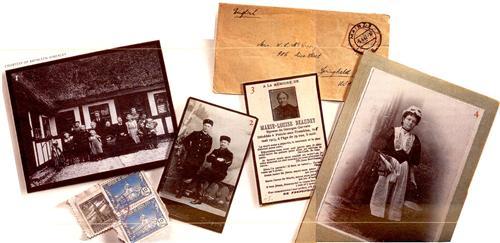

1. Sorensen Family of Brylle Fyn, Denmark c. 1900. Notice the thatched roof on the building and the bicycle in the corner. Just two members of this family immigrated to South Dakota in 1914.

2. The details in a military uniform help identify a foreign photograph.

3. Check family collections for additional photographs like the one on this memorial card.

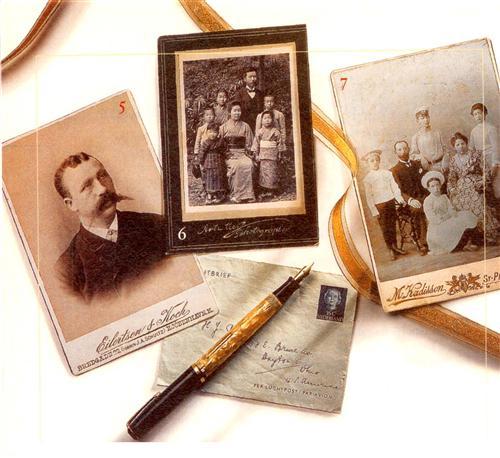

6. Ethnic and regional costumes provide clues to a family’s origins.

7. Many individuals wore contemporary clothing rather than ethnic dress.

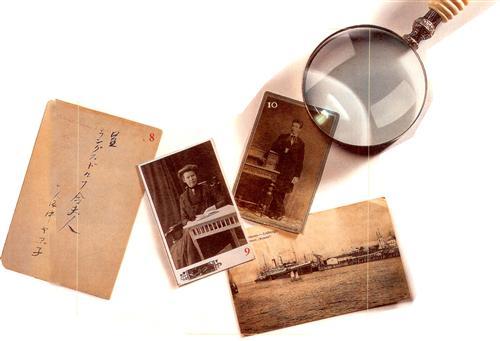

8. The caption on this photograph dates the image but needs translation.

9. Pay attention to props in images. The table in this picture is not American in design.

10. This young man’s clothing and pose are an interesting variation of standard dress. He may be a student.

Clothing clues

Clothes in a picture offer another way to identify immigrant origins. Most people in urban areas wore clothes that followed the current fashion, which can make identification of the time period — but not the country — easier. You might find it helpful to consult books in the American Family Album Series by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler. As you study your immigrant photos, look for these distinct clothing types that can provide further clues:

• Military uniforms: A significant clue to the original ancestral homeland is finding a picture of a person in military dress. Pay attention to the prominent features of the uniform such as hats, braiding, patches, shape and style of pants and jackets, and any props, then consult one of the many encyclopedias for military dress. (These same tips apply to anyone photographed in any type of uniform, including work-related clothing.) The picture below of two men in their double-breasted military uniforms with knee-high boots and insignia helps place them in Finland. The additional clues in a photographer’s imprint can narrow down where and when they posed for a portrait.

• Work or trade dress: Working men in most countries wore loose shirts, work pants and sometimes hats. Some tradesmen wore distinctive clothing that identifies their occupation, and may even help place them in a geographic context. Don’t forget to look in the background for equipment and working conditions. You can date and place an image based on mechanical contraptions as well as costume.

• Ethnic or regional variations: Ethnic and regional dress depended on local culture, not necessarily political boundaries. For instance, Gypsies traveled across Europe, but their style of dress didn’t necessarily change when they crossed into other countries. Pay attention to any details in a person’s dress that do not reflect contemporary fashion — they could be a clue. A photograph of a Japanese family in traditional dress identifies the country of origin, but if there’s also one family member photographed in contemporary dress you can estimate a date for the image.

Magnifying the details

Once you’ve translated the photographer’s signature and associated clothes with dates and places, it’s time to pull out the magnifying glass and pay attention to the photograph’s other elements. A stamp, an outdoor sign, a prop or other details may reveal facts you couldn’t find before.

• Postal clues: When postcards became popular in the late 19th century, many individuals chose to have their portraits created as postcards to mail to other relatives. Even before postcards, you could mail images along with a letter. A quick trip to your public library can reveal a great deal of data about the stamp or postmark on the letter or postal card. Philatelic societies in your area may be able to help if you have trouble finding what you need in postal history books. One stamp dates a picture and places it in a particular country — how much luckier can you get? A few places to look for answers on the Web include the Worldwide Stamp Identifier and SCV Stamp Identifier.

Postcards have an another use: The messages on the back reveal family history. Lynn Betlock of the New England Historic Genealogical Society translated a message on the back of a photo postcard of a relative standing in front of her house in Norway and discovered the story of the woman’s new house and telephone service. Not a lot of genealogical data, but it added to the social history of the family.

As you research your family in another language, it helps to make a list of reference terms that relate to family history. Include family relationships on that list. It could help you decipher the message without using a translation service.

• Props: Never underestimate the value of a prop; it may tell you where a picture was taken. Photographers in different countries included a variety of props just as American photographers did, hut sometimes these props are distinctive. One woman held a photograph of a fountain in her portrait. Her descendants are searching for the identify of the fountain, since it was obviously a picture of a place she once lived. Or you may have a photo of an ancestor holding a book written in another language — that provides a clue.

Interior scenes can reveal products, furniture and even items showing religious beliefs. Some people even posed for portraits with the tools of their trade, such as a milkmaid who held her stool in one hand and a bucket in the other. While props can be mysterious, once researched, they can help you decide location and time frame for a picture.

• Location: Outdoor pictures contain scenery, signage and buildings, all of which can tell you about your ancestors. Even if the photograph was taken in the United States, immigrants often posed with clues to their heritage. Analyze photographs of individuals posed in front of buildings for architectural details, which may reveal a specific regional or national style and time period. For a quick overview of foreign architectural styles, look at how immigrants influenced building in this country in Dell Upton’s America’s Architectural Roots: Ethnic Groups that Built America (Preservation Press).

• Celebrations: Since families document their history in photographs of events such as weddings, baptisms and holidays, examine those pictures for extra clues. Wedding traditions vary according to religious preference and cultural beliefs. Holiday decorations can tell you where the party was held or where a family’s ethnic roots lie. Food also can tell you about your family: Each ethnic group serves particular food at special times.

• American Family Album Series by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler (Oxford University Press Children’s Books): Series includes family history books on Americans of Chinese, German, Mexican, Italian, Cuban, Jewish, Irish, African, Japanese and Scandinavian descent.

• Folk Costumes of the World by Robert Harrold and Phyllida Legg (Cassell Academic)

• Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups edited by Stephan Thernstrom (Belknap Press)

• A New World: The History of Immigration into the United States by Duncan Clarke (Thunder Bay Press)

• A Genealogist’s Guide to Discovering Your Immigrant & Ethnic Ancestors by Sharon DeBartolo Carmack (Betterway Books)

• The Immigration History Research Center: A Guide to Collections edited by Suzanne Moody and Joel Wurl (Greenwood Publishing Group)

Following the trail

Besides using your photographs to identify where your ancestors came from, you can create a timeline of their lives in pictures. How? If you had an ancestor or group of relatives who traveled from their homeland across the US, you can track their movements through photographers’ imprints. Families posed for pictures at several points in the Americanization and immigration process. They probably posed for a picture with family members before embarkation. A copy stayed with the non-immigrants and accompanied those who left home. One of the first things families did once they were established in the US was have a family portrait taken and send that image home. In each new location, they posed for pictures and exchanged them with family overseas. By studying the photographer’s imprint on each of the images in your collection, you can gather material on places they settled.

Finding more photos

Now that you know how useful these immigrant images can be in your family history search, you probably wish you had more. Don’t settle for a meager few photos. Try these three strategies to fill out your collection with more photographs of your immigrant ancestors than you ever imagined:

1. Ask relatives.

The majority of family photographs are in the hands of relatives. One of the most overlooked steps in picture research is networking with relatives either in person, through the mail or online using message boards. Every family naturally loses track of relatives in each generation. Individuals move away and it takes only a short time for relatives to “forget” where those migrants live.

Since online message boards aren’t limited to US relatives, you might end up locating some long-lost kin overseas as well. After making contact with a previously unknown cousin, one researcher was able to make copies of photographs of a whole branch of the family. Ask about other types of family artifacts as well. A funeral memorial card may be overlooked as unimportant by a non-genealogist relative, but it might provide a photograph of the deceased person and details of her life written in another language.

2. Re-examine your research.

Your search for information on an immigrant family means looking for documents. In many cases, photographs are part of that documentation. For instance, Chinese case files from 1895-1920, located at the National Archives Mid-Atlantic region in Philadelphia, include photographs. Also, starting in 1929, all Declarations of Intentions required a picture of the individual seeking citizenship. Alien registration cards and passports may also contain images of your ancestors.

3. Check other collections.

Don’t overlook historical society collections and special places that collect immigrant photographs. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, photographers such as Lewis Hine and Jacob Riis photographed immigrant working and living conditions. While your ancestors won’t be identified by name, those images provide the historical context in which your ancestors lived.

When you decide to tackle your immigrant photographs, either to decipher or uncover more of them, take your time. Don’t forget to use a magnifying glass to search for hidden details, talk with family and research the history of your immigrant group. Finding out more about when and where your ancestors came from can lead you to new picture sources. (But keep in mind that photography dates only from 1839.) Once you’ve finished the photo analysis, don’t jump to conclusions. Remember, it’s the sum total of your clues that actually tell the story of the photograph. And there’s nothing more fascinating than unraveling a family story — especially one with foreign intrigue.

Find it on the Web

• The Northern Great Plains, 1880-1920

< https://www.loc.gov/item/2001562047/>: This online exhibit features photographs of early immigrant settlers to the Northern Plains States.

• How the Other Half Lives: Studies Among the Tenements of New York

<www.bartleby.com/208>: Full-text online version of the groundbreaking 1890 publication by Jacob August Riis.

• Minnesota Historical Society Visual Resources Database

< https://www.mnhs.org/library >: Learn about Minnesota’s past through pictures.

• Connecticut History Online

<www.lib.uconn.edu/cho>: 14,000 images of historical prints, photographs and drawings.

• Salem Public Library Historic Photograph Collections

< https://www.salemhistory.net/>: Searchable database of thousands of historical Oregon photos.

• JewishGen ViewMate

<www.jewishgen.org/viewmate>: Get help understanding your Jewish photos, letters and other documents.

• Avotaynu Postcards

< https://www.avotaynu.com/nu13.htm>: Old images of Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine.

• The Photography Collection

< https://history.denverlibrary.org/western-history-collection>: Photos from the Western History and Genealogy Department of the Denver Public Library.

Organizations

• Steamship Historical Society of America Collection

Ship History Center. 2500 Post Road. Warwick, RI 02886 (401) 463-3570

<http://sshsa.pastperfectonline.com>: Find registers, reference materials, photos and more

• National Archives and Records Administration

700 Pennsylvania Ave. NW Washington, DC 20408 (800) 234-8861

<https://www.archives.gov/>: Finding aids to collections, including those with photographs, appear online.

• Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies

18 S. Seventh St. Philadelphia, PA 19106 (215) 925-8090

<www.balchinstitute.org>: Collection features material on 80-plus ethnic groups. Web site has an online catalog.

• Immigration History Research Center University of Minnesota

College of Liberal Arts 311 Andersen Library 222 21st Avenue S. Minneapolis, MN 55455 (612) 625-4800

<https://cla.umn.edu/ihrc>: Collects, preserves and makes available archival and published resources documenting immigration and ethnicity on a national scope.

From the February 2002 issue of Family Tree Magazine