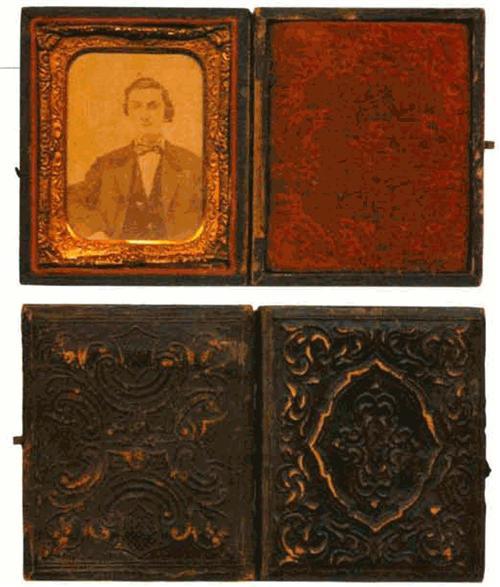

Sometimes identifying an image involves more than just analyzing clothing and hairstyle: You must recognize what type of image you have, and date the enclosure — frame, mat or case — in which you found it. But don’t worry: Even a novice photo detective can decipher this evidence by researching the answers to three key questions. To illustrate the process for identifying “cased” images, I’ll use this mystery photo, which Carole Dolisi Bean discovered in her great-grandmother Elizabeth Moll Dolisi’s sewing box.

What type of photo is it?

You’ll find four kinds of photos in cases: Daguerreotypes (popular from 1839 to 1860), ambrotypes (1854 to 1865), tintypes (1856 to the mid-1900s) and paper prints (1840 to the present). Those are broad time spans, but you can narrow the date by pinpointing the image type. How can you tell? If you have to hold a metal image at an angle to view it, it’s a daguerreotype. Glass ambrotypes often have holes in their backing material, which makes them look transparent. You’ll have to use the process of elimination to identify metal tintypes, which can resemble ambrotypes that are in pristine condition. Because the cover glass is missing on Bean’s image, I can tell that it’s a paper print.

If you can’t identify the photographic method, use clothing clues (see right) to establish a time frame for the picture. Resist the temptation to remove the image from its case. Doing so can cause damage.

How was the case made?

Each cased image has several parts: the case, a velvet liner, the image, cover glass, a mat that frames the image, and the preserver — a thin strip of metal with a paper seal that fits around the image’s components and protects them from environmental pollutants.

Cases came in a variety of sizes, shapes and designs — from simple to elaborate. Wood-framed cases, such as Bean’s, were popular in the 1840s and 1850s. They were replaced by union cases, made from a variety of substances, including gutta-percha, a tree resin that could be molded and hardened for a sturdier case.

Various shades of velvet lined the insides of most cases. Adorned with patterns, some of these liners even bear the manufacturers’ names. Unfortunately, the Bean case’s simple scroll pattern doesn’t include any manufacturer details. It does have an embossed mat and preserver, though, which suggest the case was made after the 1840s. (During that decade, these elements were plain.)

Two wonderful guides to cased images are Floyd and Marion Rinhart’s American Miniature Case Art (A.S. Barnes) and Adele Kenny’s Photographic Cases: Victorian Design Sources, 1840-1870 (Schiffer). The Rinharts’ book lists manufacturers and their years of business — a handy reference tool if your image bears its maker’s name.

The wood frame and ornate mat suggest Bean’s image was assembled in the 1850s. Does the photographic evidence support this suspicion? Let’s see.

What clothing clues appear?

The man in this picture wears a loose sack coat with a velvet collar, a patterned vest, white shirt and patterned tie. Before 1854, men’s jackets had a tighter fit, so this picture probably was taken after that year. After comparing his attire to the clothes in Joan Severa’s Dressed for the Photographer: Ordinary Americans and Fashion, 1840-1900 (Kent State University Press), I’d estimate that this portrait was taken in the late 1850s.

Interpreting the evidence

After cased photographs’ popularity waned in the late 19th century, people discarded images and used the cases for other pictures or as carrying cases. As a result, many of the photos that originally sat in cases now lie unprotected in family collections. Part of evaluating the evidence is determining whether a picture is original to its case. In this example, the dates of the case and photograph (late 1850s) are consistent, which suggests that the photographer placed this portrait in this case.

Bean had hoped that this young man, who appears to be in his 20s, was her great-grandmother’s brother August Edward Moll (born 1847). Unfortunately, the clues don’t add up. August would not be the right age for this picture. The man’s identification remains a mystery, but he must have been a special person for Elizabeth Moll Dolisi to store his picture in her sewing box — for safekeeping and to gaze upon when stitching.

From the June 2004 Family Tree Magazine