Sign up for the Family Tree Newsletter! Plus, you’ll receive our 10 Essential Genealogy Research Forms PDF as a special thank you.

Get Your Free Genealogy Forms

"*" indicates required fields

Jump to:

Details in Divorce Records

Clues to Family Divorces

Historical Divorce Law and Rules

Finding Divorce Records

Tips for Finding Divorce Records Online

Case studies and sample records

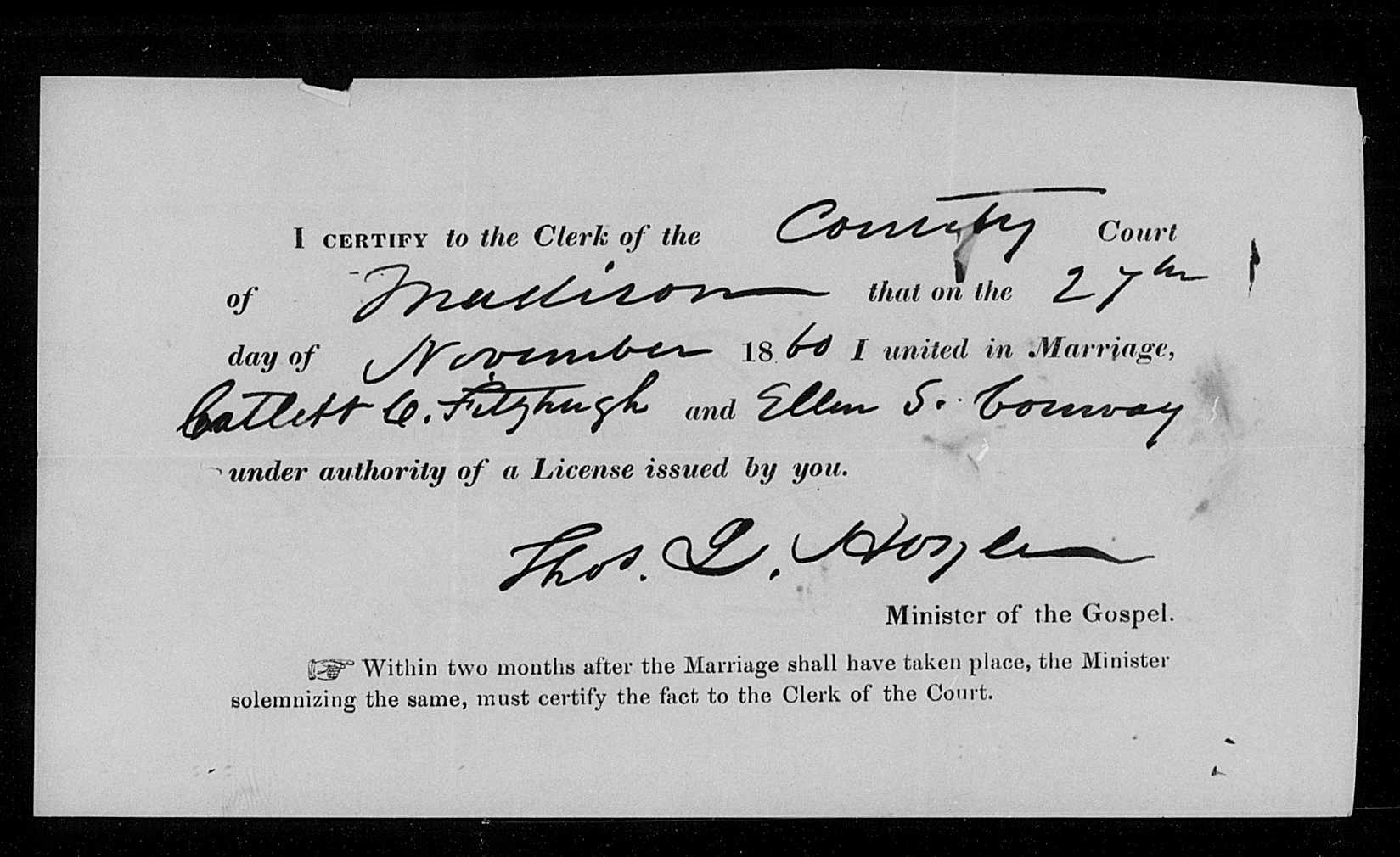

In December 1825, Amelia Alexander petitioned the Virginia state legislature for divorce. In flowery prose, she unfolded a sordid tale of her husband’s adultery, abuse and even transmission of venereal disease: “She too late discovered that the man to whom she confided her person, her happiness and her life, was unworthy. He has abused the one, destroyed the second, and more than threatened the last.”

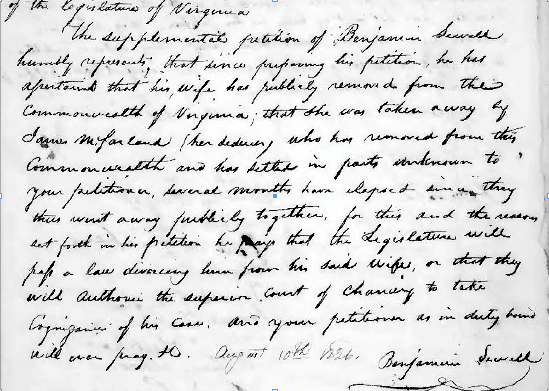

Benjamin Sewell of Russell County, Va., had a sad story, too. His wife Mary allegedly left him for another man after 18 years of marriage and eight children: “She bartered away any affection she had for her husband; for her children; the respect she had for her Sex and for herself, for the foul embraces of a vile Seducer.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Although these accounts may read like Victorian soap operas, the drama behind them was painful and real. Unfortunately for them, neither Amelia nor Benjamin won their divorce petitions. Both were denied in January 1827 by the Virginia Senate.

Today the drama and details of petitions like these (even the unsuccessful ones) can enrich your family history search. In the past, a disenchanted spouse had to convince a judge or an entire state legislature—or both—to undo the marriage.

Of course, when researching a family tree, you don’t always know when you should look for divorce records. The further you go back in time, the lower the odds that even the unhappiest couples filed. And divorce records aren’t generally as easy to find as marriage records.

ADVERTISEMENT

Use this guide to help you recognize when you should be looking for divorce records and how to find them. Divorce records are often harder to find than other genealogical resources, meaning many family historians put off looking for them. But this article will show why you shouldn’t delay even a moment longer.

Details in Divorce Records

What went awry in the relationship may be documented in almost uncomfortable detail. The couple’s entire backstory may be there, too.

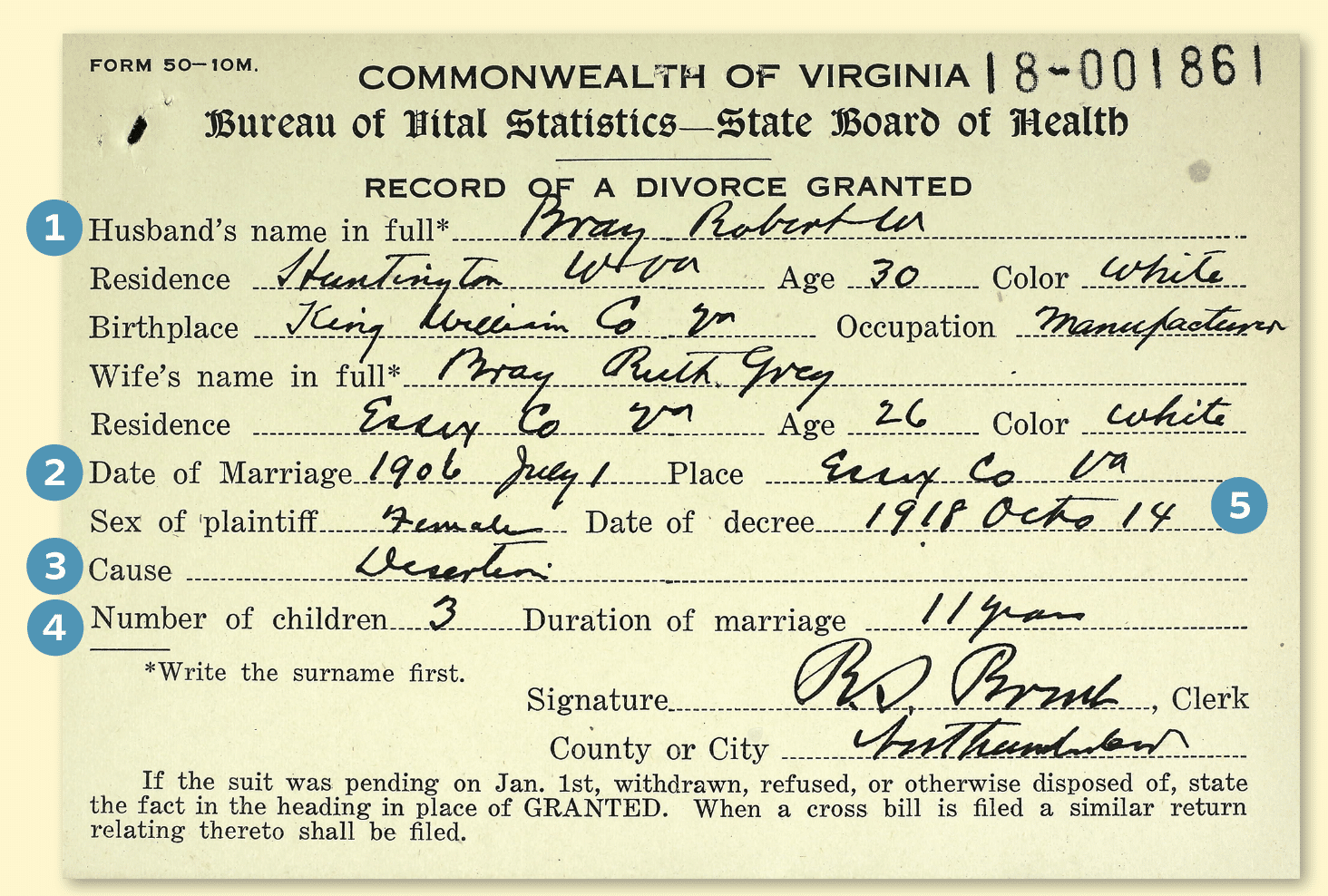

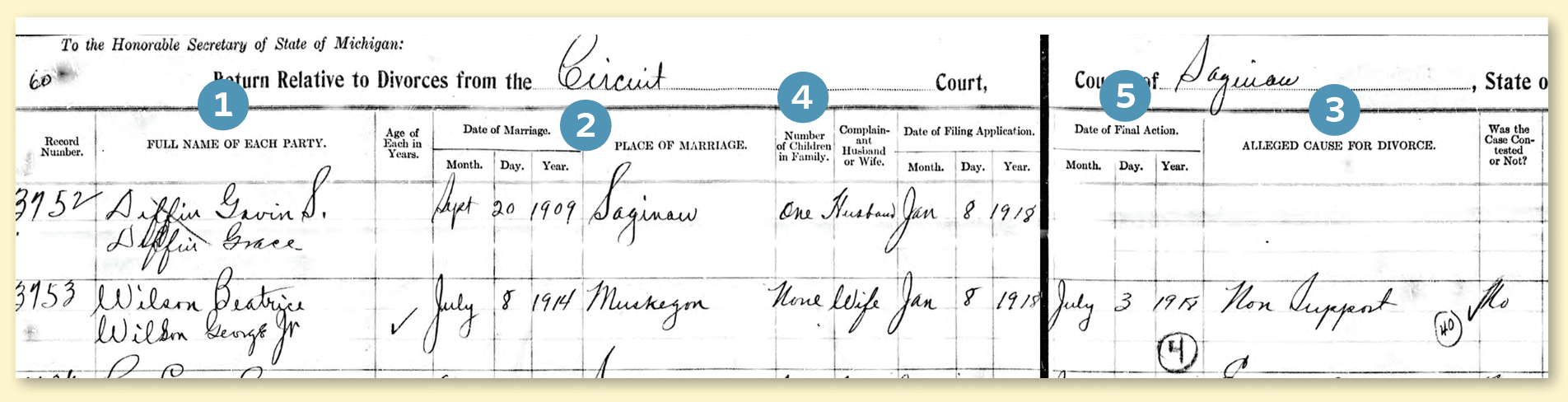

A divorce record is a genealogical treasure chest, containing not just family details but also stories and maybe even juicy scandal. At a minimum, a divorce certificate or entry in a divorce register will set out:

- Husband’s full name

- Wife’s full name (including maiden name)

- Birthdates or ages of the parties

- Residence of the parties

- Date and place of marriage

- Number of children

- Which spouse is seeking divorce, and on what grounds

- Date and place the divorce was granted

Some divorce records contain much more detail: what name the divorced wife (and her children) assumed after proceedings, the marital misconduct that resulted in the divorce, and the names and birthdates of the couple’s children.

Some adultery cases even name names—that is, they identify the person with whom the offending party had an affair. The possibilities are endless, and you won’t know in advance how much detail is in a divorce file.

Clues to Family Divorces

Before looking for an ancestor’s divorce record, you’ll likely have learned of the marriage. Marriages are documented in civil marriage returns, church registers, newspaper announcements, family Bibles, pension records and more. Records that may pair couples’ names (sometimes with specific mention that they were married) include property records, census entries, obituaries, tombstone inscriptions, their children’s birth records, draft registrations, estate documents and more.

A hint of a divorce may appear in the same record sets:

- A marriage record may indicate one spouse was previously divorced.

- Children named in census records (beginning in 1850) may have a different last name from the head-of-household, or (beginning in 1880) may be described as stepchildren to that person. (Remember, censuses provide only the relationship to the head-of-household, so you can’t tell if household members are stepchildren of a mother who isn’t the head-of-household.) Beginning in 1880, look for the letter D in the marital status column of the census.

- A deed may be executed by a married woman acting alone or identify her as a feme sole (legally a single woman).

- Newspapers published notices that one spouse would no longer take responsibility for the debts of the other, and sometimes published news of the divorce proceeding.

- Obituaries might name a different spouse or children by a former spouse.

- In cemeteries, ancestors may be buried alongside a subsequent spouse or near children from that spouse.

- Probate papers may mention children by a different spouse or financial obligations to a former spouse.

These records, however, may not reveal the whole story. Early marriage records don’t necessarily ask about prior marital history. A remarrying bride would usually use her most-recent surname, not her maiden surname. In the census and other records, a divorcee making a fresh start may have identified herself as widowed or single. Children of an earlier marriage may have taken on the name of their stepfather.

Divorce didn’t always immediately follow a separation—or even precede the next wedding. Divorce was socially undesirable, expensive and (especially in the distant past) not a sure thing. Legal grounds for granting divorce were often strict and difficult or humiliating to prove. An unhappy husband might instead go to sea or disappear onto the frontier. A miserable wife might run away with someone else: She had few legal rights over her own children and property anyway, but would have difficulty surviving on her own.

Practical consideration usually prompted an unhappy couple to finally divorce. One party may have wanted to remarry legally or at least be free of a spouse’s debts. Often one or both parties had property or children’s inheritances to protect: lawful spouses and legitimate children took precedence, even after years of separation. It may have taken time for a potential divorcee to build up the social and financial security to withstand the scandal.

Finally, there’s always the possibility that an unwitting second spouse discovered the truth and demanded things be set right. Even when records don’t directly mention a divorce or separation, you might simply guess that one happened, such as when the bigger picture you see doesn’t make sense, when names of other children or spouses pop up in records, or when women show up unexpectedly alone in records.

Historical Divorce Law and Rules

Before retracing your ancestors’ steps to divorce court, you need to know what route they took. The path may not have led through court at all. It depends on where and when a person lived and who was in charge there.

Divorce in Colonial America

The English, Spanish, French and Dutch, primarily, colonized the United States. Each colony had its own rules about divorce. Laws varied even within differently minded English colonies. There were also different levels of divorce, comparable to modern divorce versus legal separation:

- Absolute divorce or (in the language of the law) “divorce a vinculo matrimonii,” which terminated all aspects of marriage and granted at least the innocent party the right to remarry

- Divorce from bed and board (officially, “divorce a mensa et thoro”), which is similar to a modern legal separation in allowing parties to live separately and manage their own finances, but not marry again

Here’s a quick summary of divorce laws by region:

- Colonial New England: Divorce here was a civil matter that was settled in court. Grounds for granting a full-fledged divorce were relatively liberal: adultery, abuse, neglect and desertion.

- Middle colonies and Virginia: Colonial governors or legislatures granted divorces, and just for adultery, bigamy or longtime desertion. You sometimes see divorces from bed and board, but even that was relatively uncommon.

- Southern colonies: There was little tolerance for divorce of any kind. You’re more apt to find a court order for the payment of alimony so spouses could live separately.

- New Netherland: In what’s now much of New York, the colonial Dutch government pushed reconciliation by arbitration but allowed both absolute divorce and the bed-and-board kind.

- French colonial Louisiana: Divorces from bed and board due to spousal cruelty show up fairly regularly in Superior Council records. But even though laws allowed it, absolute divorce was generally a no-no because marriage was a Catholic sacrament.

- Florida, Texas and the Southwest: In the Spanish colonies, where Catholic thinking also prevailed, couples could receive a dissolution of the marriage.

When going their separate ways, wives got their dowries back and could keep their children. But they couldn’t remarry without an annulment.

Divorce in the modern United States

Later, divorce records (like other vital records) were kept by individual states, who set their own laws about when and how records were kept. As did the colonies, states also determined under what circumstances divorces could be granted in the first place.

There were exceptions to these generalizations. Marriages could be dissolved because of an underage bride or groom or because they were too closely related. In cases of adultery, sometimes divorces were granted only if the woman cheated. Ex-spouses guilty of adultery might not be allowed to remarry. In some Southern states, divorcing spouses had to get both court and legislative approval. (South Carolina didn’t grant any divorces until after a constitutional change in 1949.)

As the population grew, divorce gradually became the sole domain of the courtroom. Most states did away with legislative divorce by 1867. New US territories and states formed with more liberal divorce laws. These places became meccas for those looking for quick divorces. In 1852, Indiana allowed divorce for any “proper” reason; it had liberal residency requirements and didn’t require serving papers personally to the spouse.

Differing divorce laws between states may have encouraged residents to travel to seek divorces in states with laxer laws. These jurisdictions came to be known as divorce meccas. Utah, the Dakotas, Oklahoma and later, Alabama and Nevada, became go-to states for fast divorces.

These changes, along with decreasing social stigma, boosted divorce rates. When first measured in 1867, the rate was about 3 percent. It began climbing slowly in the late 1800s, then more quickly in the 1900s as states allowed no-fault divorces. It hit 15 percent by the Roaring Twenties and jumped to a record 43 percent in 1946, in the wake of World War II. That rate dropped back to around 25 percent until the 1970s. Between 1867 and 1967, the number of marriages in this country multiplied by five—and the number of divorces by about 50.

Finding Divorce Records

By law, those seeking divorce in early America generally had to petition the state or colonial legislatures. Over time, this responsibility passed to judicial officials in individual counties.

As a result, you’ll seek divorce records in either the legislature or the courtroom. The paper trail—and how you find records—is a little different for each.

Legislative divorces

Unhappy spouses petitioned legislatures to get divorced in some colonies, early territories and states (think Pennsylvania, New York and Virginia). In new territories, the fledgling legislatures often initially handled divorces, as in Ohio.

Petitions

The process started with an original petition, usually handwritten, from the person or an attorney. It explained, often in great detail, why the petitioner was seeking a divorce. Affidavits or other supporting documentation may have accompanied the petition. The petition was referred to the appropriate committee, which considered it and proposed a bill that then had to pass through the approval process.

If original documents still exist, they may be with the state archives or library, or in a special archive of the legislature itself. They generally weren’t published. The National Archives has a list of state-level archival repositories.

Online access to these records varies widely. One standout is the Library of Virginia’s collection of 26,000 petitions. The Wisconsin Historical Society, meanwhile, has a more-modest 2,500 petitions dating from 1836 to 1891; only a few-dozen were related to divorce.

If a family member or attorney kept a copy of the petition, it may be in a manuscript collection of the family’s or attorney’s private papers. Look for these in manuscript catalogs at regional archives.

Legislative proceedings and statutes

Any follow-up action by the state legislatures (either the upper or lower house) should appear in their legislative journals and/or statute books. Debates and amendments during the bill-approval process may be recorded in legislative minutes.

In Amelia Alexander’s case, for example, the Journal of the Virginia House of Delegates for the 1826 to 1827 session reported action on her case many times. She was given what amounted to a legal separation in February 1826. The legislature debated her request for an absolute divorce that would allow her to remarry, but eventually turned her down.

If a divorce was granted, legislators drew up a private law, which should appear among other statutes passed during the time period. Look for these first in listings of private acts (sometimes called local laws), often separate from the more general laws the legislature passed.

Journals and statute books generally were published annually, and many have been digitized. Look for these at Google Books, the Internet Archive and HathiTrust (a digital archive available through major university and research libraries).

For journal books, search with the name of the state or colony and keywords such as legislative, house or senate, and journal. Adding a person’s name and the word divorce can quickly narrow results. If you have trouble finding a specific year, repeat the search with the full title and the year you want to search. The copyright year of the journal may not be the year it covers; the book may have been reprinted or the year left off.

If you don’t find the journal you need, you may have to first research the name of a territorial or state governing body to use as a keyword. For example, Wikipedia says that Alabama’s territorial government was a “general assembly,” not a “legislature.”

For statute books, search these sites with the name of the state or colony, but use keywords such as private laws or private acts and divorce. Searching for the name of an ancestor and adding divorce as a keyword also can produce results.

Here’s a tip: Book content on Internet Archive isn’t easily searched from the main screen. Find the book first, then keyword-search within it for your ancestor’s name.

Indexes and abstracts

Genealogical societies have published abstracts of or indexes to some legislative divorces in their periodicals. Start your search for these articles in the Periodical Source Index (PERSI), Ancestry.com and HeritageQuest Online (available via subscribing libraries). A search of PERSI with the term legislative divorce brings up articles on Colonial Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Virginia, Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas and more. Most of the dates referenced in these articles range from the late 1700s to the mid-1800s.

Courtroom divorces

Almost all US divorces after 1900—and many before then, including all divorces in New England—were courtroom divorces. Whatever court had jurisdiction over equity matters handled divorces, usually the county’s circuit, superior or district court. You can find a list of courts by state in Val D. Greenwood’s book Researcher’s Guide to American Genealogy (Genealogical Publishing Co.).

Court records

In a judicial divorce (so called because a judge presided), the person seeking a divorce filed a complaint. These are often rich with marital details and discord, because their purpose was to show grounds for divorce. They often include genealogical details: the date and place of marriage and the names and ages of their children.

The original complaint, along with any response, should be in the case files or loose papers for the divorce. Similar to an estate or probate packet, this is where you’ll find the original documents related to the case. You also may discover juicy input from witnesses: transcripts of oral depositions or written answers to questions, both made under oath. You might find court orders for interim spousal or child support, or for temporary custody of the children.

A list of actions or filings in each divorce case also appears in court docket books, organized by case. Court minute books, organized by date, summarize day-to-day actions of the court—basically the same information, but organized differently and sometimes with important variations.

Ultimately, you’ll find the judgment resolving the case. Divorces could be granted, denied or even dismissed. For the oldest cases, the judgment may be all that still exists, but it may have great information in it. Look for the judgments either in a separate book of judgments or judgment orders, or in the minutes of the court itself.

Case files, loose papers, court docket case lists, court minute books and final judgments are kept with other court records. Before heading to the courthouse or sending a records request, check the court’s website or call and ask where case files for that court and year are archived.

Divorce certificates and registers

States began requiring divorce certificates and/or registers by the early 20th century. These were filed in a central office, usually the state vital statistics registrar. These only have the “bare-bones” facts of the divorce: identities of the parties, dates and places of divorce, and so on. Though they won’t contain records of the court proceeding, they can clue you to the existence of a case.

Some of these are available online, such as Ancestry.com’s collection of post-1918 Virginia divorce certificates or FamilySearch’s collection of mid-20th-century records.

You may learn that older records are sent to the state archives. You might even be able to access the court’s records on FamilySearch: Go to the FamilySearch Catalog search and run a place search for the county with the keyword divorce. Look at subsections for Court Records or Divorce Records. Many court records aren’t yet indexed, but they’re increasingly available online.

Also try searching the state archives’ online card catalog (if available). State archives microfilm might be available through interlibrary loan, or check the archives’ website for instructions on requesting records.

Substitutes

What else can you look at to document a divorce’s details? Many documents can allude to them:

- Censuses: As previously mentioned, every US census since 1880 has asked for marital status, including widowed or divorced. The 1950 supplemental questions included how many years the person had been divorced.

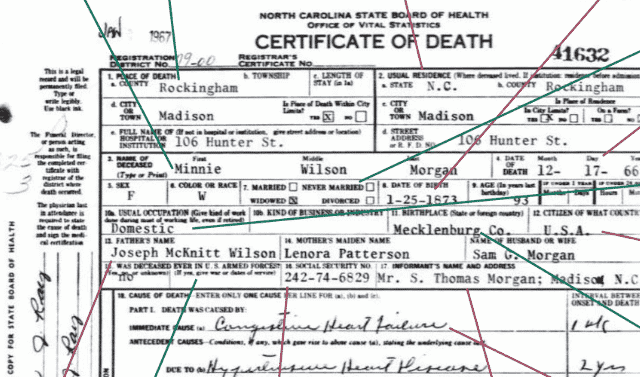

- Death certificates: Standard-form death certificates as far back as the early years of the 20th century often asked whether the deceased was single, married, widowed or divorced. Death certificates were generally filed at the state department of health or vital statistics, and older records turned over for preservation to state archives or historical societies. Many death records have been digitized and may be available at FamilySearch or even at a state archives website. Others, however, are available only as official state records and subject to state privacy laws. The websites of the appropriate state office will set out the limitations applicable to the records and the procedure for ordering them.

- Home sources: One of the best sources for any kind of family information, of course, is the family file cabinet or even Grandma’s attic. Copies of divorce orders or certificates are usually among the papers a family will file away and keep. It’s also a good idea to ask older relatives what they know about divorces in the family.

- Marriage records: Both civil and church records of marriages set out information about the prior marital status of the parties. Marriage licenses often required disclosure of any prior marriage and how that marriage came to an end. Some church records will also note prior marriages of spouses, including an indication of whether death or divorce terminated the earlier marriage.

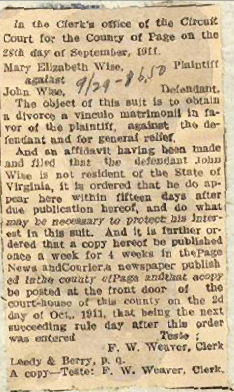

- Newspapers: These are rich resources for evidence of divorces, both in their news columns and in the sections for legal notices. The details of a juicy divorce often made page one in the local newspaper, while even a routine divorce filing might be recorded in a column on “this week’s action in the courts.” Moreover, court actions often required notice to other parties and to the public so the legal notice columns are worth reviewing as well.

- Pension Records: These may disclose that an applicant (or his spouse) had been divorced, as well as provide a recitation of marital history. In some cases, the records may disclose the conflict between a current and a former spouse. Another type of pension—known as the mother’s pension—is also worth a look. This document is available only in some states and time periods (between the late 1800s and the adoption of welfare in the early 20th century). It was intended to keep mothers together with their children in their own homes using some small public assistance. In most cases, widows and divorced women were both eligible, and both were required to set out information as to when and where they were married and how the marriage ended.

Tips for Finding Divorce Records Online

If you’re not sure whether a divorce occurred, or you need direction for where to search, an online index may provide key information. Statewide divorce indexes are a relatively recent phenomenon, and in many states, divorces within the past 50 years are sealed for privacy reasons. So most statewide divorce indexes on websites provide sparse information. Take comfort that you can get at least that, and make a note to look for originals when they become available.

Still, some divorce indexes do stretch back well before the 50-year mark:

- Archives.com has divorce indexes for about two dozen states. Most of these cover records from the mid-1900s and forward, but some go back further.

- Ancestry.com has millions of indexed divorce records representing dozens of US states and a few individual counties, some dating to the 1600s.

- FamilySearch hosts some of the same indexes for free.

If you’re pretty sure a divorce took place but can’t find it in the court of your ancestor’s jurisdiction, remember that he or she may have gone to a “divorce mecca” for a faster, easier uncoupling.

Search still coming up dry? It’s possible the unhappy pair never bothered with the formality of a divorce. But keep checking back online. Just as it may have taken your ancestors years to file for a divorce, it may take a while for the right indexes or images to appear online to help you find their paperwork and learn their sad story.

Case Studies

Sample records

- Divorce records list the names of both parties—often including a wife’s maiden name.

- Date and place of marriage suggest where you should look for more records.

- “Causes” (i.e., reasons) for divorce include “desertion,” “non-support,” and “extreme cruelty,” and may reflect what issues were legal grounds for divorce at the time. These records also indicate which spouse initiated the proceedings.

- References to children can encourage you to look for records of them—potentially under different surnames.

- Records may have separate fields for date of application and date of divorce decree.

3 steps to finding divorce records on Google Books

Intimidated by the idea of searching old law books? Try these exercises on Google Books:

- Run a Keyword Search. From the main search box on the home page, search for journal house Virginia divorce Amelia Alexander. You’ll see the 1826 Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia referencing her divorce as a top search result.

- Find a statute book for early Ohio. (Hint: Ohio was part of the Northwest Territory). Got it? The book is The Statutes of Ohio and of the Northwestern Territory, Adopted or Enacted From 1788 to 1833 Inclusive …, edited by Salmon P. Chase.

- Look in all volumes. A search on the term divorce in Volume I brings up only the legislative history (not individual divorces), so look for additional volumes. You’ll hit the jackpot in Volume III, for statutes pertaining to individual divorces.

Related Reads

Versions of this article appeared in the December 2014 and March/April 2025 issues of Family Tree Magazine.

ADVERTISEMENT